Alaska Update: ANWR coastal plain leasing at center of storm over Bush energy policy

The political furor that has erupted over proposals to allow exploration and development on the coastal plain of Alaska's Arctic National Wildlife Refuge soon will reach fever pitch.

At stake is perhaps the whole of President George Bush's energy policy, of which ANWR coastal plain leasing has been described as a centerpiece.

In support of that initiative, energy policy legislation has been introduced in the US Senate and House that would implement a program of ANWR coastal plain oil and gas leasing. Hearings by US Senate and House committees on those bills in July set the stage for an ever-more acrimonious debate that could climax with congressional votes as early as September.

Proponents of ANWR leasing admit to an uphill battle, given the current makeup of Congress. They also contend, however, that their continuing efforts to educate the public about the issue amid growing concerns over US energy supplies will enable them to eventually prevail.

ANWR background

Early indications of North Slope oil potential led to the establishment in 1923 of the 23 million acre Naval Petroleum Reserve No. 4 on the western slope to secure a US oil supply for natural security purposes.

The US government undertook a program of extensive exploration in the reserve (later renamed the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska) during the 1940s and 1950s, with a few small oil and gas field discoveries resulting.

During World War II, the entire Alaskan North Slope was withdrawn from entry by the public and set aside for US military purposes. That withdrawal was revoked by Interior Sec. Fred Seaton in 1957 on 20 million acres on the North Slope to make it available for commercial oil and gas leasing.

In the 1950s, government scientists concerned about Alaska's wilderness identified the northeastern corner of Alaska as the best candidate for protection from commercial development. In 1960, Sec. Seaton designated 8.9 million acres in that northeastern corner as the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

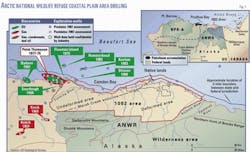

ANWR was expanded to 19 million acres from 9 million acres under the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act in 1980 (Fig. 1).

With ANILCA, another 104 million acres of federal lands in Alaska were set aside as federal conservation lands, bringing the state's total federal conservation lands to 150 million acres-nearly the combined size of California and Oregon and amounting to 70% of US national park lands and 90% of US wildlife refuge lands.

ANILCA also called for 8 million acres of ANWR to be designated as wilderness. Federal lands designated as wilderness in Alaska now total more than 57 million acres, or 62% of the US total.

However, Congress specifically left open the question of how to manage the 1.5 million acre arctic coastal plain because of the widely held belief that it contained significant oil and gas resources. In fact, it contains the Marsh Creek anticline, site of the largest undrilled structures in North America.

ANILCA Sec. 1002 directed the Department of the Interior to conduct geological and biological studies of the coastal plain and to deliver to Congress the results of those studies with recommendations as to future management of the 1002 area. But the act's subsequent section banned leasing in the 1002 area unless authorized by Congress.

In 1987, Interior recommended to Congress that the 1002 area be leased for oil and gas exploration and production in an environmentally sensitive manner. Eight years later, both the House and the Senate passed legislation containing a provision to authorize leasing in the 1002 area, but President Bill Clinton vetoed it.

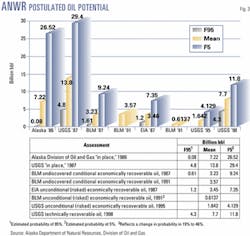

The US Geological Survey in 1998 issued revised estimates of oil and gas resources in the 1002 area. That new assessment was the strongest case yet for the coastal plain's vast hydrocarbon potential, offering a mean estimate of 10.4 billion bbl of oil recoverable.

ANWR potential

Chief among the believers in the oil and gas potential of ANWR's coastal plain is Roger Herrera, arguably the dean of North Slope explorationists and a geologist who had been involved in North Slope oil and gas exploration for the predecessor to BP PLC from 1960 until his retirement in 1993.

Herrera now serves as a consultant for Arctic Power, a Washington, DC, nonprofit citizens' lobby group devoted solely to securing oil and gas industry rights for leasing, exploration, and production on the ANWR coastal plain. The group has 10,000 members, mostly in Alaska, and is funded by individual contributions, the state of Alaska, and some oil industry organizations.

Herrera testified July 11 before the House Committee on Resources on the Arctic Coastal Plain Domestic Energy Security Act, part of a comprehensive energy bill that Rep. James Hansen (R-Utah) introduced in July.

In his testimony, Herrera complained about "...the distortions that have been applied to the US Geological Survey estimates [of ANWR oil potential] by environmental organizations."

He cited the 1998 USGS assessment (Fig. 2), which concluded that, "at $25/bbl oil and with an oil recovery factor of 37-38%, there was a 95% chance that the coastal plain could produce 5.7 billion bbl of oil over a period of 25+ years and a 5% chance that almost 16 billion bbl could be produced."

Herrera took issue with USGS use of a $25/bbl oil price as much too high: "It does not take into account the huge cost efficiencies of the new arctic drilling technology..."

At the same time, he said, the USGS errs on the low side with regard to the oil recovery factor, citing recent estimates that Prudhoe Bay oil field will eventually produce as much as 60-65% of OOIP.

Herrera contends that if the mean figure of 10 billion bbl of oil or more might be produced from the ANWR coastal plain, "such an amount would represent the largest new oil province found in the world in the past 30 years."

ANWR geology

Another believer in ANWR's underevaluated hydrocarbon potential is Ken Boyd, formerly director of the Alaska Department of Natural Resources' Division of Oil and Gas, who stepped down from that position in January 2001. Previously a geophysicist for Gulf Oil Corp., Boyd is now a consultant on retainer with Arctic Power.

"Under ANILCA, Congress issued a mandate that said that companies were supposed to evaluate the ANWR 1002 area for its oil and gas potential," he told OGJ. "Twenty companies shot 1,415 line km of seismic over 2 seasons: the first season was with dynamite, the second season was with vibrators. It was a broad grid, about 3 by 6 miles. With the ANWR coastal plain's complex geology, that level of coverage is completely inadequate, so under the mandate, it hasn't been evaluated. You can't keep reprocessing the same data. We need to at least incorporate [data from] some new wells on the periphery [of the ANWR coastal plain]."

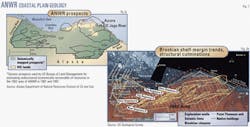

What understanding there is of the geology underlying the ANWR coastal plain, that view has shifted, according to Boyd.

"Now we believe most of the oil is in the undeformed area, 80%, vs. the deformed area. The USGS now thinks that the structures in the deformed area are gas-prone; velocity analysis suggests that the rocks appear to be gas-prone."

Boyd puts the likely resource potential of the deformed area at "at least a couple of tcf."

What's important about this shifting view of the coastal plain geology that the key oil plays are stratigraphic plays in the undeformed area is that it puts the bulk of the coastal plain's oil potential much closer to the existing North Slope infrastructure. The infrastructure closest to the most likely targets in the undeformed area is only about 30 miles away-less than the distance of the pipeline from the 429 million bbl Alpine field to the Kuparuk River-Prudhoe Bay infrastructure.

Geologically, there are several different kinds of plays in the ANWR coastal plain (Fig. 3). Closer to the Brooks Range, in the deformed area, the targets are most likely to be found in a "big overthrust play," Boyd said.

"In the undeformed area, you have very shallow-water, bar types, turbidites, some deltaic plays. Turbidites are being discovered all over the slope now, and that's because of 3D seismic."

By example, Boyd noted that the first Tarn prospect area well (between Kuparuk River and Alpine fields) was shot with 2D, as was the Bermuda well; both had noncommercial shows.

"[The operator] went back and shot some high-quality 3D...and the four Tarn wells after 3D were all successful."

The use of 3D has revived exploratory interest in the North Slope's oil and gas potential, even in areas that companies had walked away from, particularly as success rates improve with the tool. Boyd notes that the success rate for exploratory wells on the slope had been about 2-3 in 10, but now it's closer to 4-5 in 10. Furthermore, technological advances ensure that exploratory reassessment can be done with much less impact to the tundra than in the past, when early, summertime seismic surveys left lines in the tundra vegetation that still haven't been fully restored.

All exploration on the slope is now undertaken on ice in the winter, and there is no travel on the tundra after breakup (annual spring thaw).

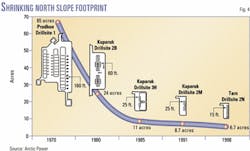

And recent field developments on the slope illustrate the ever-shrinking footprint of the oil and gas industry on the slope (Fig. 4); Alpine is the latest such prototype (see related article following this one).

Given such technology advances and new geological knowledge, that makes the case for reassessing ANWR's coastal plain more compelling than ever before, Boyd contends.

It would also boost E&D across northern Alaska, such as in the Beaufort Sea, NPR-A, and western offshore, Boyd contends.

"Opening ANWR would encourage companies to invest more in other slope exploration because of the conviction that the [trans-Alaska] pipeline would be sustained," he said.

Native concerns

Alaska and the oil and gas industry continue efforts to counter arguments against ANWR leasing-arguments that have been repeated since the issue of exploration and development on the ANWR coastal plain first arose.

Concerns have been raised by environmental groups and some native groups about the viability of the Porcupine caribou herd, which migrates from Canada to the ANWR coastal plain. About 7,000 Gwich'in Indians live in 15 villages south of the coastal plain along the migratory path of the caribou and have subsisted on the animals for generations.

In a statement, Gwich'in representatives said, "Oil drilling in this beautiful area would violate the human rights of the Gwich'in native peoples, pollute the pristine wilderness of the arctic refuge, and threaten the survival of the Porcupine caribou and the Gwich'in."

The Gwich'in noted a 44% mortality rate among calves in the Porcupine herd last year and expressed concerns over how calves would fare this year because of an earlier-than-usual thaw making it difficult to cross the Porcupine River to get to the coastal plain calving grounds.

However, Arctic Power notes that the four caribou herds that frequent northern Alaska have populations that rise and fall in natural cycles. It cites evidence that the Central Arctic herd, which frequents the greater Prudhoe Bay oil field area, has increased fivefold since oil development started in the early 1970s.

Arctic Power questions whether the Porcupine herd even uses the 1002 area that extensively.

"In most years, the bulk of the Porcupine herd use other areas of the arctic refuge, studies by government biologists show," Arctic Power said in an information brief. "Studies from 1982 to 2000 by the state of Alaska's Department of Fish and Game and in 2000 by Yukon Territory's Renewable Resources Department show that over those 18 years, only 43% of the Porcupine herd used the 1002 area."

At the same time, the Inupiat natives living on the North Slope coastal plain strongly support ANWR leasing and E&D and dispute the Gwich'in claims. The Inupiat, an Inuit group, notes that it, too, subsists on the Porcupine caribou herd, yet they remain unconcerned about the effects of oil development on caribou in the 1002 area, citing the flourishing Central Arctic herd.

North Slope indigenous people are all shareholders in the native-owned Arctic Slope Regional Corp., which owns subsurface rights to 94,000 acres in the 1002 area. It was on lands owned by the North Slope Inupiat village of Kaktovik that Chevron Corp. and BP Exploration (Alaska) Inc. drilled the only well in the 1002 area-the KIC Jago River No. 1, often dubbed "the tightest hole in history" because only a handful of company and government officials know the results of that well. Accordingly, results of that 1985 well, later plugged and abandoned, and the seismic survey that preceded it were unavailable for use in either USGS or Alaska DOG oil and gas resource assessments of the 1002 area.

Under federal law, ASRC is prohibited from developing oil and gas on 1002 lands until Congress approves exploration on the rest of the ANWR coastal plain.

The Inupiat have also pointed to their southern neighbors' own efforts to lease lands for oil and gas exploration during the 1980s. While those exploratory efforts were unsuccessful, the Inupiat claim that the Gwich'in failed to incorporate provisions to protect the caribou in their own oil and gas leases-measures that the Inupiat insisted upon before allowing Prudhoe Bay oil field development to proceed.

The Inupiat also note that the state's largest native group, the 90,000-strong Alaska Federation of Natives, supports ANWR coastal plain development.

Other ANWR issues

In his testimony, Herrera also disputed the view that ANWR development would not yield oil for many years, noting the proximity of the refuge to an existing pipeline to the Prudhoe Bay infrastructure 25 miles away.

Citing the presence of the recently discovered Sourdough oil field on the western edge of the 1002 area, Herrera said that part of the field underlies the western edge of the refuge's coastal plain.

"It is possible that that known deposit would be developed very quickly after the first lease sale," he testified. "Consequently, because only a feeder pipeline 25 miles long would be necessary to link to the trans-Alaska pipeline, first production from the coastal plain could be expected as quickly as 2 or 3 years after leasing took place.

The claim is often made that ANWR's potential oil supply isn't worth the environmental risk, because it would provide only a 6-month supply of oil.

"That's the stupidest of the all the arguments," Boyd said. "Take the median estimate of 10.3 billion bbl...at a rate of 1 million b/d, that would last for 20-30 years, an amount that could offset all of the Iraqi production the US is importing."

"Besides, would we stop growing corn in Iowa just because we're producing only 15% of the corn we consume?"

Environmental groups often claim that virtually all of Alaska's arctic coast is already open to oil and gas development, leaving the 1002 area as the last 5% of the arctic coastline undrilled.

But Sen. Frank Murkowski (R-Alas.), in a Dec. 10, 2000, editorial written for the Washington Post, dismissed that claim as "nonsense."

'Only 14% of the entire 1,100 mile arctic coastal plain is open to oil exploration," he wrote.

Murkowski also pointed out that if the higher-case estimate of coastal plain oil potential of 16 billion bbl were to be borne out, it would be equal to current levels of US imports of oil from Saudi Arabia for 30 years.

Education, lobbying efforts

The education and lobbying campaign by Arctic Power and others to open the ANWR coastal plain to drilling remains a struggle.

Arctic Power got its start in 1992, and it is funded mostly by the state of Alaska, but also in part by industry organizations. Whatever its funding level, it has been heavily outspent by the environmental lobby in the battle over ANWR coastal plain leasing, Boyd noted.

"The educational process has been very slow," Boyd said. "The environmentalists have been very successful in picturing ANWR as the 'Serengeti of the North.'"

In fact, Boyd and others have complained that the environmental lobby has deliberately misrepresented all of ANWR as the area of oil and gas industry interest-and that the media in general have taken the bait.

"The media will take pictures of the Brooks Range and call it ANWR. But the public doesn't realize that there are a couple of ANWRs," he said. "Whenever you see how the media picture (ANWR), there are always pictures of the Brooks Range; you never see pictures of the coastal plain."

In fact, the hordes of media representatives from all over the world that have converged upon the North Slope have created something of a cottage industry in additional travel to the slope. And the resulting publicity has spawned a booming business in ANWR tourism. Some outfitters specializing in ANWR wilderness adventure travel have reported increases in business of 50-70%. The last time ANWR tourism saw such a big increase in business was at the end of the 1980s, when Congress was considering legislation to authorize exploratory drilling in ANWR. That tourism boom continued into the early 1990s, propelled by concerns over the fate of Alaska's wilderness in light of that legislative push and the March 1989 Exxon Valdez tanker oil spill in Prince William Sound off the state's southern coast.

Boyd contends the "other ANWR," the coastal plain, "is a pretty unlikely vacation destination."

"The truth is that if there was any place in Alaska that you would want to drill [without compromising wilderness values], that would be it. The people who live there want it, and you can't make the argument about the caribou any more, because the herd has grown so much since Prudhoe Bay started up.

"First, it's an ugly place-flat, treeless, like the rest of the slope. You can't even make the argument for [the coastal plain being considered] wilderness. It's not pristine," Boyd said, noting human habitation there for hundreds of years. " The best...

high wilderness value area in ANWR is not the coastal plain."

He cites biological studies that found the coastal plain lacking in biological diversity. "There's much greater diversity of biology in the NPR-A than there is on the ANWR coastal plain," he noted, adding that the Clinton administration had held a successful lease sale in NPR-A that has already resulted in significant oil and gas discoveries there.

In addition, Boyd points out, industry's advances with extended-reach drilling technology enable it to avoid drilling in the most environmentally sensitive areas.

That's where Alpine field development has been cited as industry's latest effort to push the envelope in terms of using new technology to further reduce the impact of oil and gas operations on sensitive arctic ecosytems; the field is the first on the slope to be developed exclusively with horizontal wells, allowing for unprecedentedly tight spacing of wells on the surface.

Alpine is being developed in the middle of one of the North Slope's largest braided river deltas, Boyd said, and yet even the environmental community cites the project "as a good example of what's being done right by industry on the slope."

When it comes to what the environmental lobby has to say about ANWR, "no level of protection is adequate," Boyd said. That's because, he contends, science and industry's track record have little do with why environmental lobby groups have made ANWR leasing their No. 1 issue.

"ANWR is a moneymaker for the environmental community," he said. "They want to keep this [dispute] alive strictly as a means of raising funds."

Bush administration stance

Including ANWR coastal plain leasing in a national energy policy plan was arguably the boldest move the Bush administration could have made on energy policy, given the history of partisan rancor over the issue.

By all accounts, the move has galvanized the environmental lobby in Washington like nothing since the appointment of ecolobby bogeyman James Watt as Secretary of the Interior 2 decades ago. Many environmental groups have reported sharp increases in donations since Bush was elected president, and especially since he unveiled an energy policy plan cobbled together by a task force, the National Energy Policy Development Group, under Vice-Pres. Dick Cheney-who like Bush, has ties to the petroleum industry and thus is also a lightning rod for antileasing critics.

While that plan focuses on a broad swath of recommendations for solving US energy woes-including measures promoting conservation, energy efficiency, renewables, and fiscal incentives for conventional energy production-most of those have been overlooked in the furor over ANWR. And that has given rise to speculation by some Democrats that the Bush administration intended for ANWR to be, in fact, a lightning rod for critics of the energy plan and thus deflect attention from other recommended measures that would be a boon to the oil and gas and coal industries.

"While ANWR is a critical piece of the Bush energy plan, we have to make the point that ANWR isn't the only piece," Boyd said.

Specifically, the NEPD task force recommended that the president "direct the Secretary of the Interior to work with Congress to authorize exploration and, if resources are discovered, development of the 1002 area of ANWR. Congress should required the use of the best available technology and should require that activities will result in no significant adverse impact to the surrounding environment."

To help gain support for ANWR leasing, the NEPD Group also recommended that the president direct the Interior secretary to work with Congress to create a Royalties Conservation Fund. This fund would be designed to 1) earmark potentially billions of dollars in royalties from new oil and gas production in ANWR to fund land conservation efforts and 2) to help eliminate the maintenance and improvements backlog on federal lands.

The subtext of the latter provision reflects a criticism the Bush administration has made of the Clinton administration's push to greatly expand the amount of federal lands under wilderness or other protected-status designations, while a number of studies have shown the federal government already lagging badly in efforts to maintain existing parklands.

It also points to the deep philosophical divide between the Bush and Clinton administrations in their respective stances regarding resource development on federal lands.

That point was driven home with Interior Sec. Gale Norton-herself a lightning rod for criticism from environmental groups as a onetime protógé of former Interior Sec. Watt-appointing Cam Toohey, previously the director of Arctic Power, as her special assistant for Alaska.

That appointment drew blistering criticism from antileasing forces. Rep. Ed Markey (D-Mass.) issued a statement blasting the appointment as "breathtaking in its arrogance toward the public interest, and a new low point for the Bush administration."

But Norton later defended her choice as representing the views of Alaskans and the Bush administration, both of whom support ANWR coastal plain E&D.

If there had been apprehension by the petroleum industry over the Bush administration perhaps backpedaling from support of ANWR leasing in order to salvage his energy initiative, those fears may have evaporated with Toohey's appointment. In a sense, it represents Bush drawing a line in the sand with opponents of his energy policy.

Uphill fight in Congress

The battle to secure leasing on ANWR's coastal plain has been an especially fierce one and will only get fiercer as an actual vote approach, which could be as early as September, according to Herrera.

Many Democratic leaders have already proclaimed the effort futile, contending ANWR leasing proponents do not have the votes.

A widely reported statement made during a press conference in Washington, DC, and attributed to Ted Stevens, one of Alaska's two Republican senators, gave the impression that the staunch backer of ANWR leasing had deemed the effort dead in the water.

But Stevens, in a letter to Alaska Gov. Tony Knowles, said that his comments were taken out of context and that he actually told the press conference that backers of ANWR leasing "do not have the votes here right now because of the misinformation that has been given to the country [by opponents of ANWR leasing]; we'll get the votes.

"I also noted that we did not have the votes on the [trans-Alaska] oil pipeline, ANILCA, or statehood at this point in the sessions we considered those issues; with hard work, we prevailed."

Boyd acknowledged the uphill fight facing proponents of ANWR leasing in Congress, but noted, "Votes are subject to change. It might take something like an energy crisis hitting closer home-like if in [a particular] district, if people couldn't afford to heat their homes."

Stevens has said that supporters of ANWR leasing can count on the votes of 48 senators, with another 3 straddling the fence. And those fence-straddlers are reportedly senators from states where the biggest labor unions have a great deal of political clout.

A number of key labor unions have lined up in favor of ANWR leasing, ostensibly in response to backers' claims that ANWR E&D could create many jobs. In an economic analysis of ANWR coastal plain oil and gas development, Wharton Econometrics Forecasting Associates estimated that such development could create as many as 736,000 new US jobs, throughout all the states.

Earlier this year, an alliance of big organized labor and business groups created Job Power, to promote ANWR coastal plain E&D. Notable among those big labor unions is the powerful, 1.5 million-member Teamsters union, which has launched its own lobbying effort at the state and national levels.

While the ANWR debate isn't exclusively partisan, certainly the Democratic Party-which now controls the Senate with the recent defection of Vermont Sen. Jim Jeffords from the Republican Party-generally opposes ANWR leasing. That makes the support of Big Labor for opening ANWR even more critical, as labor organizations have long been part of whatever bedrock support Democrats have enjoyed over the years.

Even beyond the creation of jobs, ANWR development appeals to labor groups for another reason: its potential to increase US oil supply and thus contribute to a softening of high energy prices that threaten to spur huge layoffs in energy-dependent industries.

Stevens contends that similar concerns over the effects of continuing high energy costs on the US economy will help build momentum for support of ANWR leasing.

"When gasoline is $3/gal on the East Coast, [ANWR leasing legislation] will pass," he told a press conference in Anchorage May 30. Stevens was alluding to predictions by some analysts that gasoline prices could soar to $3/gal in some regions of the US in 2002.

However, US gasoline prices and natural gas prices have softened considerably in recent months. It was difficult enough for ANWR leasing advocates to press their case by citing the current energy crisis while critic pointed out that startup of any oil or gas production is some years away and would do nothing to solve immediate energy supply concerns. Already, some supporters of ANWR leasing worry about the window of opportunity for their cause, as temporarily weakening energy prices may lull Americans back into complacency about energy shortages. Yet they also warn that a US oil import dependence projected to grow to more than 60% this decade from the current level of about 50% underscores the urgency of ANWR coastal plain oil development.

As many have pointed out, it took an act of Congress to get the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System authorized-and that was in a political climate freshly charged by an oil supply crisis and a recession blamed largely on rocketing oil prices in the 1970s.

Given growing regional tensions over the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, the perpetual predilection for Iraq's Saddam Hussein to cause mischief with oil markets, and the leanness of spare oil production capacity in the world today, the stage may be set for a repeat of those circumstances.

"[The ANWR leasing push] will be really difficult in the short term, absent some real energy crisis affecting more than just California," Boyd added. "But sometime in the next 2 years, the possibility [of such a crisis occurring and thus bolstering support for ANWR leasing] is very high."

null