Politics, production levels to determine Caspian area energy export options

Caspian Sea region oil exports have a much brighter future than they did 2 years ago now that crude oil prices have risen again. Total production and transportation costs-excluding Russia's-for bringing Caspian oil to market is $8-10/bbl, so oil prices must be near $18/bbl to make Caspian oil investments worthwhile. Long-term projections foresee prices stabilizing at $22-27/bbl.

The current exploration focus is on Kazakhstan's offshore Kashagan deposit and on gas discoveries in the South Caspian area. The dearth of drilling rigs operating in the landlocked Caspian Sea and recent price constraints have both played a role in restraining exploration to date.

Russia's influence

Caspian area oil production could increase to 3.9 million b/d by 2010-and natural gas production to 200 billion cu m/year-if adequate export pipelines are developed and area investment continues. Gas production also depends on access to Russia's pipelines and growth in both domestic and accessible foreign markets.

Most proposed pipelines, however, are enmeshed in political, legal, financial, or technical difficulties.

The Soviet Union built most of the existing oil and natural gas pipeline network in the Caspian Sea region, and they flow towards Russia, thus eliminating most export routes to other markets. Most of the old oil pipelines also have technical problems due to lack of proper maintenance.

In 1996, the International Energy Agency reported that oil pipelines from the Caspian Sea to Russia had a functional capacity of 324,000 b/d, with almost no export capacity. Thus, oil available throughout the next decade will require additional pipelines.

Natural gas exports from the Caspian region face an even greater problem, given the current infrastructure. OAO Gazprom, Russia's state natural gas company, has not allowed Caspian gas exports to reach outside markets through Russia.

Gazprom had not wanted Caspian natural gas to compete with Russian gas in profitable European markets, but now the company wants to buy Caspian gas and resell it to Europe in lieu of charging tariffs for use of its pipelines.

Russia appears to prefer selling cheap Turkmen gas before exporting her own. In 1999, Russia estimated its natural gas reserves at 48.14 trillion cu m, 32.9% of the world's total. Turkmenistan's proven natural gas reserves are only 1.9% of the world's total.

Security

Multiple export pipelines would increase energy security by making total export disruption less likely.

Because most pipelines pass through or near politically troubled areas such as Dagestan and Chechnya in Russia or near the Nagorno-Karabakh region in Azerbaijan, obvious concerns rise over energy security. The current situation in Chechnya has already shut down some lines.

Economic feasibility, however, has been perhaps the most important issue since the 1998 crude oil price crash.

Producers have proposed oil pipelines to European markets via the Black Sea and the Mediterranean Sea, while considering others to the Persian Gulf via Iran.

Competition

Caspian crude oil-of a higher quality and cheaper to produce than Russia's-can compete strongly with Russian crude but not with Middle East crude oils, because Caspian extraction and transportation costs are higher.

There is more intense competition for natural gas pipelines than for crude oil pipelines, because gas pipelines must compete with established, closer suppliers in all markets.

It might be cheaper for Russia to import Caspian gas for its own domestic use, freeing up Russian gas for export, although currently Russia plans to buy Caspian gas and export it to Turkey via the Blue Stream gas pipeline.

Turkey is currently the prized growth market for Caspian Sea natural gas. Turkmenistan, once thought the frontrunner for gas exports to Turkey via the Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline (TCGP), signed a 30-year supply contract with Turkey in October 1998. However, Turkmenistan could lose that position as Turkmen President Saparmurat Niyazov stalls over preferences to export the gas via Iran rather than Azerbaijan, which demanded transit fees of at least 50% of TCGP's initial 16 billion cu m/year capacity (see related article, p. 70).

The US definitely would oppose any export route via Iran, however, and two proposed pipelines through Afghanistan are unrealistic. Turkmenistan now is left with few other options to bring its huge gas reserves to market. Exports to Russia are an available option and seem likely now that price differences have been settled.

If TCGP collapses, the new frontrunners to supply gas to Turkey will be Azerbaijan and Russia, with its Blue Stream pipeline.

Oil supply, demand to 2020

The future of oil production in the Caspian Sea area depends on its proven reserves, which are expected to increase over the next 5 years when major drilling is completed.

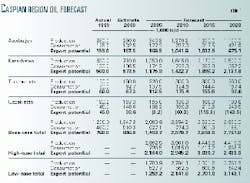

Most crude oil reserves are in Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan. As of Jan. 1, 2000, Azerbaijan had about 7.5 billion bbl and Kazakhstan, 15 billion bbl. Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan are unlikely to export their limited volumes, and Uzbekistan may become a net oil importer by 2005.

Table 1 contains the area forecast for crude oil production, consumption, and export potential.

While Russia is not included in this study, it should be noted that OAO Lukoil recently discovered an estimated 2 billion bbl of oil in the Russian section of the Caspian Sea. Iran also has production possibilities in its section. Lasmo Oil PLC recently speculated that potential Iranian Caspian reserves could be 10 billion bbl of oil and 566 billion cu m of gas.

Water depths to 3,000 ft and a regional shortage of deepwater rigs will make ex- ploration costly for Iran's Caspian sector, however-$5-7/bbl compared with $2/bbl for the Persian Gulf.

Oil production, consumption

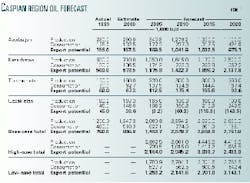

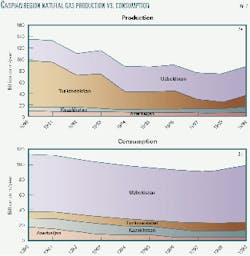

Fig. 1 shows crude oil production and consumption in1990-99, with the early 1990s being the peak years for consumption. The countries have still not returned to those levels. Only Uzbekistan has in- creased oil production since 1991, yet it still doesn't have enough crude reserves to export. Uzbekistan will likely import more than 100,000 b/d by 2015.

Altogether, the Caspian Sea region is expected to produce nearly 4 million b/d by 2015. Kazakhstan will produce more than 50% of the total volume, and Azerbaijan, 15-30%.

All the countries, except Uzbekistan, have adequate reserves to meet their domestic needs. During 1991-97, the countries could produce only what they consumed and about 50% more to export to other former Soviet Union states.

In 2000, Azerbaijan agreed to import Russian gas for use in power generation, so more crude would be available for export. Azerbaijan's base-case demand scenario assumes an average annual growth rate (AAGR) of 6%.

When the Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC) crude oil pipeline comes on line later this year, it should significantly boost Kazakhstan's economy and drive consumption. Increases in production from Kashagan, Tengiz, and other fields will also help drive the economy and increase consumption.

The growth rate may decline, however, after 2005.

It is unlikely that Turkmenistan's economic growth will increase significantly in the near future, so demand growth will likely stay close to the base-case scenario of 3% AAGR.

Uzbekistan's new refinery in Bukhara, ultimately to have a refining capacity of 272,000 b/d, could enable that country to meet the high-case growth scenario in 2005. The base case assumes little growth, as Uzbekistan is already one of the more developed Caspian region countries.

Oil export availability

Under the base-case scenarios and anticipated reserve levels, Caspian region export volumes will increase to 1.5 million b/d in 2005 and to 2.5 million b/d in 2010.

By 2015, export potential should peak just below 3 million b/d, decreasing to 2.7 million b/d by 2020.

Because Caspian Sea production depends on a few key projects, changes or delays in those plans could affect production profiles substantially. With higher long-term oil prices, Caspian oil is less remote and more accessible than before. Caspian Sea crude oil production will peak at 4 million b/d by 2015 in the base case, by 2010 in the high case, and by 2020 in the low case.

The influx of Caspian crude should not cause oil prices to change much. By 2010, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries will have a greater share of the world market than it does today. Produc- tion from non-OPEC producing regions will have declined by then, and it is likely that the Caspian area will fill the void.

Natural gas

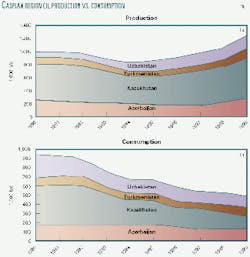

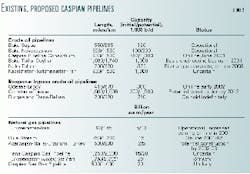

Unlike oil, Caspian gas development depends more on market demand than on available reserves. Reserves are high throughout the region, with Uzbekistan being the only country that will become a net importer in the long term. The region has about 8.0 trillion cu m of natural gas reserves, with 3.1 trillion cu m just in Turkmenistan. Azerbaijan has only 0.6 trillion cu m; Kazakhstan, 2.0 trillion cu m; and Uzbekistan, 2.1 trillion cu m. Table 2 contains the natural gas forecast.

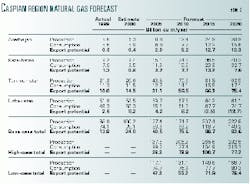

Fig. 2 shows natural gas production and consumption by Caspian area countries.

Natural gas production will not peak until 2020. The highest growth rates will likely be in Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan, although Turkmenistan will surpass Uzbekistan as the largest producer sometime during 2005-10. Turkmenistan would likely meet any natural gas demand increases in the Caspian area that cannot be met domestically.

Azerbaijan's base-case natural gas production forecast is a likely scenario, as BP PLC plans to export natural gas from Shah Daniz offshore field.

Questions have arisen over what Turkey's gas demand will be after Russia's Blue Stream pipeline comes on line.

Natural gas from Karachaganak and associated gas from Kashagan and Tengiz fields will increase Kazakhstan's gas production. Tengiz alone is producing nearly 1 billion cu m/year of associated gas. Over the next 10 years, Kazakhstan plans to eliminate all natural gas imports, which will limit volumes available for export.

Uzbekistan's base case comes from likely decreases in regional exports due to a lack of payment and competition from the other states, which are all located closer to markets. Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan also have significantly stronger ties with foreign investors and more experience in exporting gas.

Gas consumption

Natural gas consumption will increase as distribution systems are developed, gas-fired power plants constructed, and industry use increased. The rate of increase will depend on funding for gas projects and the ability of the consumer to purchase gas.

Unlike oil demand, gas demand experienced only slight decreases or moderate growth during the inflationary period of 1991-97. The governments subsidized the gas and maintained supplies even when economics may have dictated otherwise.

No one has enough money to purchase Azerbaijan's large, recently discovered volumes of gas. The Azeri government even has plans to import Russian gas for heating this year. The imports will be financed with money earned from exporting the crude oil volumes they displace.

Kazakhstan's base-case scenario is derived from the projected replacement of aging power plants with new, combined-cycle, gas-fired power plants, together with the expected reduction in its imports of electricity and gas.

With increased oil revenues and a more efficient internal gas pipeline network, new power plants are likely. Gas would fuel them due to its relative availability and its cleanliness compared with the high ash-content coal that currently generates 80% of Kazakhstan's electric power.

Turkmenistan's demand will hover around its base-case scenario, as gas is highly subsidized, and no one has the currency to purchase more gas. In 1999, Turkmenistan's electricity sector consumed 35% of available Turkmen gas; industry and other sectors consumed 55%; and the gas industry, 5-10%.

No new power plants are planned, as Turkmenistan has excess electric power generation capacity of at least 1.5 billion kw-hr that it would like to export.

Uzbekistan's natural gas demand, already high, will increase slowly. Most of the country's power plants are natural gas-fired, and Uzbekistan was the FSU's fourth largest exporter of electricity in 1997. New gas-fired power plants are therefore unlikely.

Upgrades will make existing gas-fired power plants more efficient, thus potentially decreasing the amount of gas consumed, so Uzbekistan could even see slightly negative growth in gas demand. Some vehicles have been converted to run on compressed natural gas, and CNG filling stations exist, but it has been difficult to find investors.

Natural gas export availability

Under the anticipated level of reserves, export availability will likely peak around 2015, as Uzbekistan becomes a net importer of gas and Caspian area consumption requires more gas. Production could be increased to make more gas available for export, but further potential export market growth is uncertain. Investors looking to export gas may also be scarce in the long term due to difficulties in securing purchase contracts and finding available export capacity.

Natural gas exports will first occur through Russia's Blue Stream project and then from Azerbaijan to Turkey. Turkmen natural gas will also be exported, as Iran will substantially increase the volume of its imports, and Russia has agreed to purchase Turkmen gas. TCGP may eventually be built, if Turkmenistan can reach a satisfactory capacity-sharing agreement with Azerbaijan.

Turkmenistan's other plans for exports are unlikely, as there is no funding. Eco- nomics would have to justify any gas pipeline option. If the South Caspian Sea is proved to contain mostly gas, then future investment in the region will primarily be driven by market demand and gas pipeline capacity availability.

Outlook

Politically, the best energy security is to have multiple pipelines. As recently as mid-2000, energy security planning for the West was focused on avoiding export pipelines through Iran and Russia. The US government was the strongest advocate of avoiding the two countries, but continued high oil prices through third quarter 2000 have altered the situation.

US interests now are more concerned with getting Kazakh oil to market than how it gets there. The new US administration will likely support this change.

Azerbaijan is still viewed as a starting point for a pipeline providing optimal energy security for the West. However, Azerbaijan International Operating Co.'s (AIOC) 4 billion bbl of proven reserves are not yet enough to justify constructing the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan oil pipeline through Turkey to the Mediterranean.

Adequate Azeri reserves have not been proven yet, because there are only two operational rigs capable of drilling in the deeper waters of the Caspian Sea. Com- panies are waiting in line to use the rigs, because the price of bringing a rig into the landlocked Caspian Sea is very high. Recently, the Offshore Kazakhstan International Operation Co. (OKIOC) consortium decided to tender a second rig for its Kashagan discovery.

This decision came only after OKIOC became convinced of the field's potential. If there is more drilling success elsewhere in the Caspian Sea, one of the larger consortiums, such as AIOC, could likely bring in another rig.

Oil pipeline options

Table 3 lists existing and proposed Caspian oil and natural gas export pipelines, in decreasing order of probability (also see map, p. 70). Because of low drilling rig availability, another 2-3 years of drilling may be necessary before the South Caspian basin's potential is known.

The largest volumes of oil will be exported in the short term via the 930-mile, CPC oil pipeline from Tengiz field in western Kazakhstan to Russia's Black Sea port of Novorossiysk. It is scheduled to come on line by June 2001. Karachaganak and Kashagan fields will have significant production volumes over the course of the next decade.

The existing Baku-Novorossiysk and Baku-Supsa crude pipelines will continue to operate.

Should the Caspian region produce as much as is expected from it, the 1,080-mile, Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline could provide critical strategic surplus capacity for any Kazakh production that exceeds CPC pipeline capacity. Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan has a good chance of being completed after 2005, if AIOC finds enough oil in the Caspian Sea. Approval for this pipeline awaits ratification by the parliaments of Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey.

The pipeline would also balance the regional market in order to offset potential price manipulations posed by a second Iranian line and Iran's crude oil swap proposal. If there is no alternative, Iran could easily ask potential exporters for $7/bbl to transport the oil or swap it, as that costs slightly less than sending it by rail through Russia or Georgia.

The destabilizing affect of the $7/bbl transport cost can be seen in contrast with the $3/bbl cost of the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline. If reserves to justify its construction are inadequate, then the Baku-Supsa and the recently operational Baku-Chechen bypass-Novorossiysk crude oil pipelines may be upgraded instead.

Overall, crude oil exports will end up being shipped to the Mediterranean or will remain in the Black Sea area, potentially being transferred to the Odessa-Brody crude oil pipeline from Black Sea tankers. Once crude oil is loaded onto a tanker, it is considered on the open seas and can be sent anywhere in the world.

All other oil pipeline options are unlikely to materialize under current world oil prices and the current level of Caspian region reserves.

Gas exports

Gas to be exported is destined primarily for Turkey, with some to Iran.

The only new gas pipeline coming out of Azerbaijan in the near future is likely to be a small-volume gas pipeline to Erzurum, Turkey, where it would connect with the Turkish gas transmission network to export large volumes of gas from Shah Daniz field.

If gas discoveries continue to proliferate, a gas pipeline parallel to the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan oil pipeline to Turkey could be constructed sometime after 2005.

Gas exports to the Ukraine are sporadic, due to payment problems and arguments over the right to transport via Gaz- prom's Russian pipelines.

Plans for gas pipelines to China and Japan have been dropped, though the long term may see a gas pipeline to India via Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Iran's role

The Azerbaijan government has kept open options for oil or gas exports to Iran, but many speculate that this is just to foster good relations between the two countries. However, Turkmenistan may yet export some crude to Iran in the future-if Iran is willing to fund it. Significant oil swaps from Kazakhstan or Turkmenistan to Iran may occur in the next couple of years, but they will not approach 370,000 b/d until 2006. Small-scale swaps, however, will continue.

Europe may eventually purchase Caspian gas through pipelines as well. There are signs that US sanctions against Iran are lightening, and the new administration may lift them.

If they are lifted before construction begins on a main export route, such as the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan crude oil pipeline, then further large-scale export routes through Iran may be proposed. It is possible that Caspian oil could be piped to the Persian Gulf rather than the Mediterranean.

If Iran were to produce from its own area of the Caspian Sea, it might be more interested in building a pipeline from the Caspian to Iran and then reversing one of its pipelines to the Persian Gulf.

The more likely scenario with Iran, however, is that Caspian area crude oil swaps with Iran will continue until reaching Iran's 500,000 b/d limit. In addition to its security precautions, Iran is unwilling to reconfigure refining capacity for more than 500,000 b/d of Caspian crude.

Iran would not build a main export pipeline to the Persian Gulf for Caspian Sea oil other than its own. The Neka-Tehran oil pipeline capacity is only 370,000 b/d, and flow depends on the demands of northern Iran.

If the Iranians were to receive the maximum amount of swapped oil that they could allow, the issue of exporting to Iran would be moot, and the US would not have to worry about high volumes of exports under Iran's control.

The argument over Iranian sanctions is the fight for money involving the early small-volume oil exports. International companies have invested much money in the Caspian Sea with little return.

Iran is the cheapest export option, because the oil is consumed in northern Iran and does not have to be piped or shipped via tanker outside the region. Mobil Oil Corp. (now ExxonMobil Corp.) and other international companies in Turkmenistan wanted to swap oil with Iran, but the US, raising the specter of sanctions, denied permission.

The sanctions have done little to hurt Iran, but they have hurt the US companies that are waiting for a chance to reap a return on their Caspian investments.

Russia won

In the pipeline game, Russia has won. The CPC line passes through Russia, and Russia will export Turkmen gas to Turkey via its Blue Stream gas pipeline. The race for early oil and gas has ended, as CPC will come on line in mid-2001 and Blue Stream will be complete by mid-2002.

Areas with substantial proven reserves came on line first-in this case, Tengiz crude in Kazakhstan and Turkmen gas. Turkmenistan's loss is that it now must share a significant portion of its export revenues with Russia. Turkmenistan is also now more dependent on Russia and Iran for revenues via gas exports.

Georgian instability could further enhance Russia's position. If Russia were to occupy Georgia as a peacekeeper for regional stability, it could control the flow of oil through the Baku-Supsa line. If the extension to Ceyhan is completed, Russia's victory would be even more complete.

The author

Robert R. Smith is a senior associate at FACTS Inc. and a researcher at the East-West Center in Honolulu. His research focus is on downstream oil and natural gas markets and energy policy issues east of the Suez Canal. He holds an MA in Asian studies from the University of Hawaii and a BA from Johns Hopkins University.