NEWS Shifting pattern of U.S. oil import sources tests viability of deepwater port projects

A.D. Koen

Senior Editor-News

Refiners in the U.S. have relied increasingly on crude oil feedstock imported from Latin America and Canada since the Iraqi war of 1990-91.

Estimates by the Energy Information Administration (EIA) show non-U.S. producers in the Western Hemisphere combined this year through May to account for more than half the crude imported into the U.S.

The trend in part eases concern that runaway growth of U.S. crude import volumes will force excessive reliance on supplies from Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries members in the Middle East.

Long term, few expect anyone but Middle East producers to outlast competitors in world crude markets. But in the short term, the new mix of U.S. crude imports is raising nettlesome questions for domestic deepwater oil ports, present and future.

As U.S. refiners have grown more reliant on so-called short haul imports, relentless competition on world crude markets has been forcing producers to move shipments internationally by the lowest cost paths that safety will allow.

More and more Latin American producers are shipping crude oil to the U.S. in tankers small enough to reach marine oil terminals on the mainland. As a result, crude throughput is down at the nation's only deepwater oil port, a 1.4 million b/d facility in 115 ft of water 18 miles off Louisiana in the Gulf of Mexico built and operated by Louisiana Offshore Oil Port Inc. (LOOP), New Orleans.

LOOP's perspective

Similar to the belt tightening that has swept through the rest of the U.S. petroleum industry, LOOP officials have responded to the trend with a reorganization plan.

The emphasis is on restoring LOOP's imported crude throughput with incentive user fees and on finding new uses for the port's facilities. But officials also have launched a round of cost cutting.

To trim spending, LOOP has been renegotiating some supply and services contracts.

It also is seeking relief from the regulatory straitjacket that limits the company's business agility. The lack of flexibility interferes with LOOP's ability to compete with lower cost -- but riskier -- ways of importing crude into the U.S.

In addition, LOOP employees for most of the summer have been weighing a severance package offer.

Taken alone, recent inroads by short haul crude into U.S. markets are not especially troubling to sponsors of two active deepwater port proposals. The trend underscores the need for deepwater ports to be able to compete for throughput from any available source against other ways of importing crude oil into the U.S.

The Oil Pollution Act of 1990 (OPA 90) set oil spill liability levels for deepwater ports at a hefty $350 million. Previously, the Deepwater Port Act (DWPA) of 1974 set LOOP's oil spill liability limit at $50 million.

With earnings likely to be squeezed by competition from less costly alternatives, few sponsors of new deepwater ports would be willing to accept the high financial risk required by OPA 90. So the act lessens the likelihood that a new deepwater port will be built.

Challenge to new ports

The challenge presented by OPA 90 appears most daunting to officials at Blue Dolphin Energy Co., Houston. Blue Dolphin is organizing a group to develop Petroport, a deepwater facility in 120 ft of water about 45 miles off Freeport, Tex.

Blue Dolphin Pres. Michael Jacobson said U.S. crude oil import trends have not diminished his company's conviction that another deepwater port is needed in the Gulf of Mexico.

"There is sufficient long haul crude entering the U.S. to support another deepwater port in the gulf, especially off Texas," Jacobson said. "A new deepwater port, however, must be competitive with alternative means of bringing oil into the U.S."

Jacobson said the fee structure Petroport could put in place would be commercially competitive.

Farther south on the Texas Gulf Coast, officials of the Port of Corpus Christi still are backing construction of Safeharbor deepwater port, now to be located in 100 ft of water about 20 miles off Mustang barrier island. First proposed as a shore based facility, sponsors describe the revised Safeharbor port as a simplified version of LOOP.

"If we're not competitive with lightering, the project is not going to get done," said Jim Shiner, president of Shiner, Moseley & Associates Inc., the Corpus Christi engineering firm working on Safeharbor's design.

Relief from OPA 90

Fortunately for deepwater port officials, OPA 90 allows a path of possible reprieve.

The act requires Department of Transportation (DOT) officials to study relative operating and environmental risks posed by deepwater ports vs. other modes of marine shipments of crude oil.

The U.S. Coast Guard last September published findings of an oil spill risk analysis of LOOP. Coast Guard officials estimated LOOP's maximum spill to be about 5,200 bbl of oil, and DOT on Aug. 4 published a rule in the Federal Register trimming LOOP's liability limit to $62 million.

Engineering and environmental factors of new deepwater ports in the future could differ significantly. So DOT said it will assess risks posed by each proposed new deepwater port before setting its liability limit between $50 million and $350 million.

The lower limit will not change deepwater ports' liability for spills caused by gross negligence, willful misconduct, or violation of certain federal rules. But companies should be more willing to join groups sponsoring new deepwater port projects if the lower liability limit significantly lessens capital costs.

Import patterns

With imported crude entering the U.S. in growing volumes, news of LOOP's slumping throughput in the past couple of years comes as something of a surprise.

However, U.S. strategists since the Arab oil embargo of 1973 have tried to diversify sources of crude oil imports. And since the Persian Gulf war with Iraq, that effort has picked up momentum.

EIA data show U.S. crude oil imports during January-May 1995 averaged 6.988 million b/d, about 540,000 b/d more than in the same period of 1993 and nearly 1.42 million b/d more than in 1991.

Short haul producers serving U.S. import markets this year through May shipped more than 3.5 million b/d of crude to the U.S., or 50.1% of imported crude entering the country. Supplies included among the short haul volumes came from Argentina, Colombia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico, Peru, Trinidad and Tobago, Venezuela, and Canada.

Short haul suppliers in 1991 through May shipped 2.399 million b/d of crude into the U.S., or 43.1% of total imports. During the same 5 months in 1993, short haul supplies amounted to about 44% of total U.S. crude imports.

Overall, short haul suppliers during January-May of this year had captured more than 1.1 million b/d of incremental crude demand in the U.S. since 1991, or more than 77.7% of the total increase. Leading short haul suppliers, their exports to the U.S. this year through May, and the increases since 1991 are:

- Venezuela with 1.13 million b/d entering the U.S., nearly 520,000 b/d more than in 1991.

- Canada with 1.01 million b/d, up 200,400 b/d.

- Mexico with 958,100 b/d, up 201,500 b/d.

Ecuador, meantime, boosted its exports to the U.S. to 123,000 b/d, 73,700 b/d more than in January-May 1991. Colombia this year through May sent 183,200 b/d of crude into the U.S., up 54,200 from 1991.

Significantly, long haul suppliers, defined here as all other net exporting countries, in January-May 1993 accounted for slightly more than half of the total 876,000 b/d increase of imported crude entering the U.S.

But while U.S. imports this year through May increased 542,000 b/d since 1993, short haul supplies to the U.S. jumped by 667,000 b/d. In the same period, long haul supplies entering the U.S. declined by 125,000 b/d.

Shifting patterns

Growing U.S. reliance on short haul supplies has been a big factor driving LOOP's throughput down to levels not seen since the 1980s.

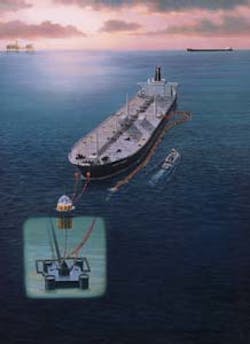

Designed to handle very large crude carriers (VLCCs) of 170,000-318,999 dwt and ultra large crude carriers (ULCCs) as large as 700,000 dwt, LOOP began service in May 1991 (OGJ, May 18, 1981, p. 30).

LOOP officials at the time estimated the cost of the facility at $737 million, little more than half its estimated cost in 1995 dollars.

Even in the early years of operation, the facility struggled to attract customers.

LOOP throughput in November 1982 reached 415,000 b/d, with one tanker offloading every 2 days (OGJ, Dec. 6, 1982, p. 122). Throughput since the facility opened had averaged 250,000 b/d, with 35% of the volume coming from Mexico, 35% from the Persian Gulf, 17% from North Africa, and 13% from the North Sea.

LOOP on July 9, 1983, set a 1 day throughput record by handling 1.5 million bbl of crude (OGJ, July 18, 1983, p. 59). But despite that surge, the facility's June 1983 throughput averaged 393,000 b/d, and monthly volumes in the first 2 years of operation averaged about 276,000 b/d, or less than 20% of capacity (OGJ, Aug. 8, 1983, p. 66).

Effects on LOOP of the August 1990 disruption of U.S. oil imports from Kuwait and Iraq at first seemed short lived. Companies shipping oil to the U.S. from the Persian Gulf quickly replaced Kuwaiti and Iraqi supplies.

LOOP throughput wavered but held firm, averaging 913,000 b/d in 1990 and 917,000 b/d through August in 1991 (OGJ, Sept. 30, 1991, p. 22). Nominations from tankers seeking to offload oil at LOOP surpassed 1 million b/d throughout summer 1991.

But throughput has been declining ever since.

LOOP in first half 1992 received an average 800,000 b/d of imported crude. In January 1993, the facility handled less than 700,000 b/d, and through yearend 1994 throughput averaged 779,000 b/d.

That trend has accelerated this year. LOOP crude throughput in the first 6 months of 1995 averaged only 617,000 b/d.

Case for reorganization

LOOP officials say increased volumes of short haul imports mean more crude is entering the U.S. in shipments of 500,000 bbl or less aboard tankers of 170,000 dwt or smaller.

R.C. (Bob) Thompson, LOOP president, says the deepwater port is at a disadvantage when competing for such short haul volumes because it can't handle smaller tankers as efficiently as bigger vessels.

The sum of a long chain of transportation costs and fees determines the cost of delivering a barrel of imported crude to a U.S. refinery gate. Costs associated with importing facilities is only a part of the total cost.

LOOP's system of user fees costs vessels about 41/bbl to offload at the facility. For VLCCs and larger tankers, the per barrel cost averages about 38. For LR-2 vessels of 80,000-169,999 dwt, the smallest craft using LOOP, the cost averages 45/bbl.

That fee structure apparently doesn't compete well with the cost of landing short haul crude shipments directly on the mainland in smaller tankers. There also is some question about whether LOOP's current costs are competitive with alternative ways of importing long haul crude into the U.S.

According to most estimates, long haul suppliers transshipping or lightering crude from VLCCs or ULCCs at sites in the Caribbean region are able to land crude at mainland ports and marine oil terminals for 25-30/bbl.

LOOP officials say most of the facility's throughput decline has occurred because of evolving patterns of waterborne crude imports. But other supplies are contributing to the situation.

Incremental crude imports from Canadian producers enter the U.S. by way of international pipelines.

Thompson said Canadian supplies compete for market at many of the same Midwest U.S. refineries served by LOOP by way of the Capline pipeline system. In addition, growing U.S. production in the Gulf of Mexico competes for Gulf Coast markets LOOP is set up to serve.

"That has a tendency to back out imports that might enter the U.S. through LOOP," Thompson said.

Reversing the trend

DOT's decision this month to lower LOOP's liability limit was the latest in a long campaign to reduce costs at the facility.

In addition to cost cutting steps in operations, LOOP has refinanced debt at lower rates of interest. The port has made all operating changes allowed within the tight framework created by the DWPA and LOOP's federal deepwater port license.

Bill Jennings, LOOP vice-president of operations, says the facility is saddled with a set of rules stemming from the early 1970s when government officials were oriented more toward micromanaging petroleum activities.

"To this day, we are required to maintain an elaborate environmental monitoring program that is levied on us with a substantial effect," Jennings said.

He estimates the cost of complying with safety and environmental mandates at the facility at millions of dollars yearly.

"When you take the Deepwater Port Act, pull together 50-75 pages of regulations, and add a license that is very detailed," said Tom James, LOOP secretary and general counsel, "it creates a straitjacket in which a deepwater port must operate."

In addition to undermining LOOP's ability to compete in an evolving crude oil marketplace, Thompson said, the requirements have discouraged construction of new deepwater ports.

Plans to boost revenue

While LOOP has been trying to reduce costs related to regulatory mandates, it has been seeking ways to hike income by more aggressively marketing the facility's capabilities.

Again, federal rules limit what the deepwater port is allowed to try.

But LOOP last year introduced a new barrel incentive rate to its customers. Under the plan, LOOP allows a qualified shipper an 8 discount on each barrel of crude offloaded at the facility that exceeds the customer's throughput in the same month a year earlier.

In June of this year, the company began offering a negotiated space available rate. After LOOP receives nominations within its regular monthly cycle, officials begin contacting other potential customers, trying to match openings in the facility's log to scheduled arrivals of U.S. bound crude shipments.

"If shippers have cargoes coming through our area when we have an opening, we try to negotiate a special rate with them if they will agree to use LOOP," Thompson said. "That rate typically is pretty competitive with the cost of lightering or direct mainland deliveries."

Thompson said the space available rate in June attracted four or five shipments in June and July that would have entered the U.S. through other means. Most of the cargoes LOOP has attracted with the program were being shipped aboard LR-2 tankers.

Wooing Latin producers

In an effort to compete head to head for more short haul crude volumes, LOOP also is trying to convince South American crude exporters to consolidate small shipments onto larger tankers and move the combined shipments to LOOP for offloading.

Shippers' savings would flow as much from streamlining their export and transportation paths as from the relative cost of using LOOP. But Thompson says LOOP in its own right brings many benefits to the negotiating table.

He says shippers can offload more safely at a deepwater port like LOOP than through other ways of exporting crude into the U.S. They also benefit from the use of LOOP's Clovelly, La., salt dome storage site and a distribution system tied to more than 30% of U.S. and 80% of Louisiana's refining capacity.

In addition, South American oil shippers would benefit from the lower unit freight cost of transporting crude with VLCCs or ULCCs.

The Caribbean island of Bonaire off Venezuela has a marine terminal in 110 ft of water that can receive VLCCs and ULCCs regardless of their lengths or widths. Several other sites can load LR-2 vessels, but nothing larger.

In addition, officials have proposed other marine crude terminals based on single point mooring systems that could be built within a year or so, Thompson said.

If more short haul crude entered the U.S. through LOOP, vessel traffic at U.S. mainland ports and on inland waterways would decline.

"Domestic refineries were not built to rely on foreign crudes," Thompson said. "And with volumes of imports that are coming in through them today, they don't have enough dock capacity and related infrastructure."

As a result, vessels seeking to offload at a refinery dock on the mainland might have to wait a long time before being allowed to dock.

"We can streamline their operations tremendously by packaging cargoes on superships and bringing them in at LOOP," Thompson said.

Handling domestic crude

LOOP officials knew as early as 1990-91 that significant offshore crude oil production would come on line in this decade in the Gulf of Mexico. However, they were uncertain whether the DWPA and LOOP's deepwater port license allowed the facility the freedom to pursue business opportunities in- volving domestic crude.

In the early 1970s, political leaders and oil company officials advising them assumed that so much imported crude would be entering the U.S. in the coming decades that deepwater ports wouldn't have time or capacity to handle domestic crude.

"Back then, it was thought LOOP might have to be expanded to handle as much as 3 million b/d of oil," Thompson said.

Instead, some industry observers today predict deepwater crude oil production in the gulf will amount to as much as 500,000 b/d by 1997 and 1 million b/d by 2000.

A year long effort to get permission from federal regulators for LOOP to handle domestically produced crude oil culminated late last year. Shell Pipe Line Corp., Houston, in December 1994 disclosed plans to lay a $100 million, 200,000 b/d subsea crude oil pipeline system (OGJ, Dec. 12, 1994, p. 28). The 200,000 b/d pipeline system is to transport crude from new deepwater fields in the gulf to a Chevron facility at Fourchon, La.

Shell plans to lay 130 miles of 18 in. and 24 in. crude line from the Mars tension leg platform on Mississippi Canyon Block 807.

Shell also is laying 120 miles of 12 in., 20 in., and 24 in. to LOOP facilities at Fourchon from Bullwinkle field on Green Canyon Block 143. Dubbed Amberjack, the Bullwinkle-Fourchon pipeline also is to intersect Boxer field on Green Canyon Block 19, as well as offshore tracts in the Ship Shoal, Ewing Bank, and South Timbalier federal planning areas.

The Mars and Amberjack lines are to be complete next year. LOOP expects to begin receiving crude from Amberjack in first quarter 1996. Mars is to begin producing by yearend 1996.

For its part, LOOP for the past 112 years at Clovelly has been building a 3 million bbl salt dome storage cavern to be dedicated to crude delivered by the Mars-Amberjack pipeline system.

A Shell official said, based on current deepwater crude discoveries in their vicinities, both pipelines likely will reach capacity.

"When you look at what else might be out there -- the level of leasing activity and drilling and the focus of exploration and production -- it certainly would indicate there's still a lot of oil to be discovered," he said.

When the lines reach their initial design capacities, Shell likely will add pump stations.

LOOP also is talking with other deepwater producers in the gulf about similar arrangements.

"As far as our business strategy goes now, we see ourselves developing as a domestic oil terminal," Jennings said.

Thompson said the DWPA and LOOP's license ought to be changed to allow the deepwater port to pursue business opportunities involving domestic crude oil supplies.

"We would like to have the liberty to do that without having to go to Washington to seek approval every time an opportunity crops up," he said.

Safeharbor, Petroport

Safeharbor proponent Shiner says officials developing the deepwater port need no regulatory changes to press ahead with the project.

Safeharbor sponsors have reviewed the facility's new plan with federal officials and have developed a set of estimated costs. According to those figures, the breakeven point for throughput on the new design would amount to about 185,000 b/d. At that level of activity, the cost of offloading at Safeharbor would be about 28.5/bbl.

Noting that each oil company calculates lightering costs slightly differently, Shiner said approximate equivalent lightering cost would be 34-35/bbl.

"If we could add another 50,000-100,000 b/d to our throughput, the per barrel costs start dropping to the 22-24/bbl range," he said. "Then it really starts making money for the companies using it."

[TABLE "How sources of US crude oil imports have changed" (32247 bytes)]

Shiner says the situation confronting LOOP illustrates the main difficulty sponsors face in planning deepwater ports: predicting the sources of crude imports.

"Where will the oil be coming from?" Shiner asked. "And if a monobuoy makes sense today, will it make sense in 7 years or 10 years?"

Blue Dolphin's Jacobson said that even in the current competitive environment, Petroport's unique design should allow it to be profitable.

On the one hand, owners must cover the cost of construction, amortization of capital costs, and generation of an appropriate rate of return. On the other, a deepwater port must price its services within the marketplace.

"Petroport's capital cost structure is extremely attractive for a deepwater port, substantially less than what LOOP cost and a fraction of what the replacement cost for a LOOP-type system would be," Jacobson said.

Because it has such low capital costs and expects to have low operating costs, he said, Petroport should be able to provide "very attractive service priced competitively with lightering at today's costs."

Petroport in its license application intends to specify the use of updated operating guidelines and of modern instrumentation and equipment. The application will propose that Petroport use the best available technology and highly qualified employees.

If Petroport's license allows it to undertake a wider range of activities than LOOP, Jacobson gives much of the credit to its predecessor.

He says LOOP's owners must be commended for taking a huge financial gamble that has provided a valuable service to the country. "Its operating record is exemplary, and I'm glad to see some of the more imaginative measures it is taking to improve its financial performance."

Positioned for the future

Thompson assures LOOP is well positioned for an unexpected financial storm.

The facility has been profitable for the past several years and in 1994 generated a net income of $9.4 million.

"We don't think our position is nearly as bad as our throughput numbers would indicate," he said.

Jennings says LOOP officials believe the facility's current difficulties are only temporary.

"We are weathering a storm right now, and we have some strategies for diversification that will be very important to us," Jennings said. "But certainly, LOOP's long term future is tied to Middle East oil."

Copyright 1995 Oil & Gas Journal. All Rights Reserved.