Cost-cutting not enough to hit IOC growth target

Adam Mitchell Petros Farah

StrategicFit

London

International oil companies (IOCs) responded to low oil prices by cutting spending and costs while seeking to deliver more production. Corporate filings show costs will have to fall below 2010 levels for companies to reach production targets.

Companies grew exploration and development capital spending by 57% to 2014 from 2010, but still were unable to increase either production or reserves organically. Organic growth refers to finding reserves through the drillbit rather than buying reserves through acquisitions.

IOCs are cutting frontier exploration. But further change is needed if companies want to sustain their business models.

IOCs set the tone for the rest of industry. This article compares publicly available information from Chevron Corp., ConocoPhillips Inc., Eni SPA, ExxonMobil Corp., Royal Dutch Shell PLC, Total SA, and BP PLC.

Investors grew increasingly concerned during the last decade about declining upstream capital efficiency. Companies tolerated inefficiencies while revenues rose along with oil prices. Growth was the 2010-14 priority while industry remained optimistic and opened new frontiers.

IOC spending ballooned. Executives justified the increased budgets by citing rich asset bases and sanctioned projects. The companies chased increasingly marginal barrels to meet production-growth targets, underestimating the consequences of growing project complexity, a sharply tightening supply chain, and project-schedule uncertainty.

New reserves' unit costs peaked in 2014. IOCs started to review their cost base and returns on investment even before the oil-price slump. Falling prices added urgency.

Current budgets and production growth plans only can be achieved with large reductions in unit finding and development (F&D) costs or acquisitions. The changes will require one or a combination of the following actions:

• Reducing F&D costs by 60% from 2014 levels to achieve the capital efficiency needed to reach production-growth targets within existing budgets. Companies will need to find opportunities with enough scale to make them worthy of development investment.

• Increasing exploration and development (E&D) capital spending 100% compared with 2016 levels. If costs cannot be brought down, spending will have to rise to pursue sufficient exploration and produce reserves.

• Acquisitions providing 50% of new reserves and production. IOCs will need to take advantage of acquisitions as increasingly distressed opportunities become available.

It will be difficult for management teams to achieve sustainable capital-efficiency improvements. IOCs have focused on maintaining their financial position and short-term returns to investors since the oil-price plunge but are reconsidering their strategies. Executives are asking themselves if they should add a shrink-to-grow option, accelerate acquisitions to refresh assets, form new international partnerships to access new resources, or negotiate very different working arrangements with service companies.

Production targets

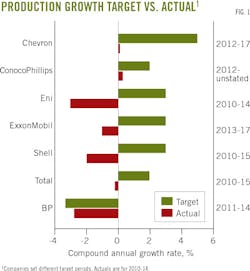

IOCs started outlining annual production-growth targets of 2-5% beginning in 2010 when prices stabilized above $80/boe. BP was the exception because it preserved cash to handle the legal and financial aftermath of the April 2010 Macondo deepwater well blowout.

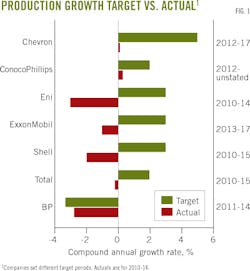

Growth targets implied increased production of 1.9 million b/d across the six majors by 2015 (Fig. 1). This growth was larger than Eni's current production. The IOCs collectively fell 2.4 million boe/d short of targets (Fig. 2).

Organic growth always has been problematic for IOCs. Targets set for 2000-05 and 2005-10 also were missed.

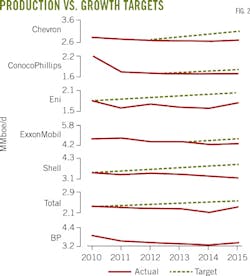

The main lever management has to address major project overruns or delays is to spend more or spend more quickly. All firms increased organic capital spending per barrel of production.

Reinvestment grew much faster than unit revenue in some cases (Fig. 3). Only ExxonMobil increased unit spending more slowly than the rise in realized price.

Total production across the seven firms fell 2 million boe/d during 2010-15. Production growth is sustainable only if reserves also grow. Lowering the reserve-to-production ratio is sustainable only if companies start with abnormally high reserves after large exploration successes or change the fundamentals of the time required to move from discovery to production.

Neither of these was true for the IOCs in 2010. Project complexity and lead times tended to increase during the period. Only Conoco and Eni grew reserves organically, but both also divested heavily to consolidate their assets (Fig. 3). Total and ExxonMobil increased reserves through large acquisitions.

Reserve replacement was less difficult for large independents. The authors' analysis of company filings for certain international independents showed these companies maintained or grew reserves 2010-14.

The analysis included Anadarko Petroleum Corp., Hess Corp., Marathon Oil Corp., Noble Energy Inc., and Premier Oil PLC.

Independents unable to grow reserves through the drillbit relied on acquisitions to replace production.

The importance of capital discipline and return-on-capital-employed (ROCE) tends to follow exploration and production cycles. Periods of lower prices lead executives to promote capital efficiency and returns, while production growth moves to the forefront with rising prices.

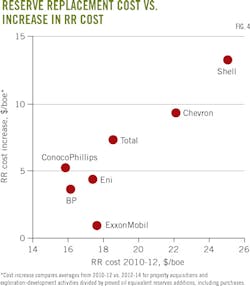

The years 2010-14 were no exception. Fig. 4 shows that all IOCs experienced higher reserve-replacement (RR) costs as they pursued production growth. Companies that started with poor capital discipline found themselves less able to control cost increases.

The rise in cost cannot simply be explained by general increases in costs in the supply chain. IHS CERA's upstream capital cost index1 only rose 15% during 2010-14, despite high oil prices. The pressure to deliver growth forced some companies to chase volumes despite diminishing returns in their portfolios.

Two other underlying causes exist for both the higher costs and unrealized growth:

• Industrywide growth tightens the service sector more quickly than it can add capacity. Costs escalate as experienced workers become scarce.

• Medium-term production targets require delivering large projects on schedule. Given the uncertainties involved in these complex projects-be they regulatory, commercial, or technical-forecasting production becomes troublesome. Projects are more likely to be delayed than delivered early.

The future

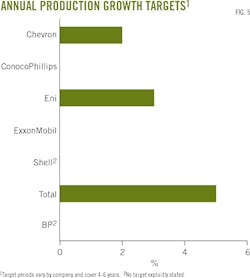

Updated strategies presented in the second-half 2015 and first-half 2016 set production growth targets for five of the seven firms (Fig. 5). Four companies set growth targets of 2-5% for the next 4 years or longer. Lower budgets are the new normal while oil prices stay at current levels.

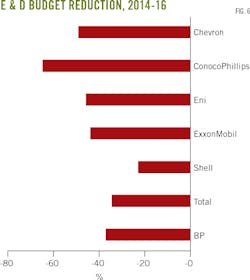

Falling oil prices have forced the IOCs to reassess strategy. Cutting operating costs and reducing capital budgets have become priorities and the reduction in spending is dramatic (Fig. 6).

There's no sign E&P fundamentals have radically changed. Companies have no reason to substantially reduce reserve-production ratios.

Additional reserves will need to replace production. The IHS CERA upstream capital cost index1 suggests costs have fallen by 24% from second-quarter 2014 to Dec. 31, 2015. Table 1 outlines the choices companies face in achieving new targets. Companies could choose a combination of options

F&D costs will need to come down another 15-35% and stay there to achieve required reserve growth. Even this, however, assumes that companies have equally prospective opportunities to explore at a time when frontier exploration budgets have been slashed or eliminated. Only Shell has substantially renewed its portfolio, by acquiring BG Group.

It's far from clear that current budgets can meet the targets. If companies continue to perform at 2012-14 levels of unit-RR cost, E&D budgets will have to rise substantially. First-quarter financial filings indicate that operating cash flow barely covers capital spending at current prices.

The table's acquisitions column indicates the annual proved reserves each company would need to acquire if current budgets delivered new volumes at the 2012-14 F&D cost.

Many mid-sized companies face cash-flow shortfalls. Banks are increasingly reluctant to expand E&P exposure. More oil and gas asset transactions are likely.

IOCs typically have focused primarily on the short-term by cutting costs to maintain investor confidence in response to low oil prices. Credit-rating agencies, meanwhile, have downgraded the ratings of most majors, despite ambitious targets.

Investors familiar with poor IOC track-records have little confidence that IOC executives will deliver on future promises without significantly changing their strategies. CEOs need to think beyond short-term needs and adapt to sustain long-term operations.

References

1. www.ihs.com/info/cera/ihsindexes.

The authors

Adam Mitchell ([email protected]) is a StrategicFit principal. Mitchell has led consulting projects in E&P, power, renewable energy, and carbon dioxide. He holds a BSc in Physics from the University of Bristol and an MBA from Imperial College Business School, London.

Petros Farah ([email protected]) is a consultant at StrategicFit with experience in upstream projects in Norway and UK. He holds a PhD in nanophotonics from the University of Cambridge.