Ohio weighs post-production costs, royalty calculations

Greg Russell

Pete Lusenhop

Steven Chang

Vorys, Sater, Seymour and Pease LLP

Columbus, Ohio

Post-production cost deductions are a common source of royalty litigation. Local lease-interpretation rules determine whether particular deductions are proper and defensible in court. Different jurisdictions, however, follow different rules to different ends.

Historically, a lease calling for a royalty based on the value of production at the wellhead has allowed the lessee to net-back post-production costs when determining the value of production upon which royalty calculations are based.

A countervailing theory, however, has been urged in some jurisdictions which requires the lessee to bear the costs of converting natural gas extracted at the wellhead into a marketable condition. This theory reasons that production-the sole responsibility of the lessee-is not complete until the gas is in a form in which it could be sold.

Under the "marketable product" theory, the lessee alone bears the cost of common post-production expenses for treating, compressing, dehydrating, and in some states, transporting oil and gas to a viable market.

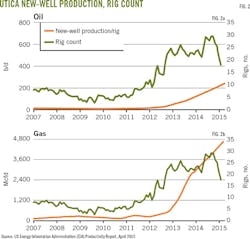

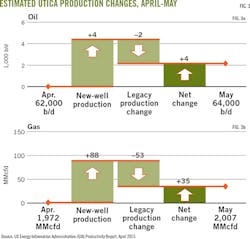

Ohio has a long history of oil and gas production stretching back to the 19th Century. Recently, however, the Utica shale has become a major contributor to US oil and gas production (Fig. 1). Yet the state has not directly addressed whether it follows the "at the well" approach or some version of the "marketable product" theory. The Supreme Court of Ohio, however, may rule on the dilemma soon. A federal court certified this question to the Supreme Court of Ohio on April 1, 2015 (see accompanying box).

With Utica production continuing to surge despite the recent drop in oil prices, a decision will affect many stakeholders in the region (Figs. 2 and 3). This article addresses how the competing "at-the-well" and "marketable product" approaches square with established Ohio contract law, and how Ohio courts, including the state supreme court, may ultimately view post-production cost deductions.

At-the-well rule

Understanding the rationale behind the two competing approaches is helpful in understanding how they conform or conflict with established Ohio law.

Jurisdictions that follow the "at the well" rule generally permit a lessee to net-back post-production expenses when calculating royalties, determining that production occurs when gas is severed at the wellhead.

Most states have either explicitly adopted the "at the well" rule or have issued decisions giving effect to "at the well" language in leases. These states include Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, California, Kentucky, New Mexico, North Dakota, Michigan, Montana, and Pennsylvania.

The courts' rationale for adopting the "at the well" rule varies from state to state but generally involves giving "at the well" language in leases its plain, ordinary meaning, recognizing that the common use of "at the well" in the industry is to permit the net-back approach to royalty calculations, or for practical considerations such as simply bringing consistency to royalty payments.

In Louisiana, for example, production occurs when the oil or gas is severed at the wellhead because that is the point at which the parties come into ownership of the commodity. Title then vests in the lessor and lessee in the proportions set forth in the lease.

Other states, such as Texas, have reasoned that the words "market value at the well" are part of a well-established lexicon in the oil and gas industry used to distinguish gas sold in the form in which it emerges at the wellhead from gas that has had value added by transportation or processing.

Other courts have reasoned that the function of the at-the-well language is to adjust for imperfect comparisons in determining market value. Deducting processing and transportation costs from the downstream value of production is a means of determining the production value at the wellhead.

Another reason offered for adopting the "at the well" rule is to ensure that lessors do not obtain different royalties depending on when and where in the value-added production process gas is sold. Because gas may be sold at several locations downstream, using a net-back approach provides consistency across royalty payments.

Marketable product theory

Only a few jurisdictions have adopted the "marketable product" theory, under which the lessees' implied obligation is to bear the burden of post-production costs until the oil or gas has been placed in a condition in which it can be sold. Jurisdictions that have adopted the "marketable-product" theory in some form include Oklahoma, Colorado, Kansas, West Virginia, and, through federal court decision, Virginia.

The most prominent rationale for adopting this theory rests on the implied duty of a lessee to market the oil or gas produced. Certain marketable-product jurisdictions have interpreted the lessee's duty to market gas as including the responsibility to process the gas into a marketable condition and, in some jurisdictions, to transport it to market.

Because the lessee bears all costs in complying with its express and implied duties under the lease, it must bear all post-production costs necessary to create a marketable product.

Other courts have premised the theory on the idea that non-operating interest holders generally have no input with respect to cost-bearing decisions. By this reasoning, royalty and overriding royalty interest holders contractually agree to receive a lesser share in the royalty in exchange for a free ride on costs incurred creating a marketable product.

In 1998, the Oklahoma Supreme Court in Mittelstaedt v. Santa Fe Minerals Inc. fashioned what is commonly referred to as the modern "marketable product" doctrine.

The court held that a royalty interest may bear post-production costs of transporting, blending, compression, and dehydration only when the costs are reasonable, when actual royalty revenues increase in proportion to the costs assessed against the royalty interest, and when the costs are associated with transforming an already marketable product into an enhanced product. If there is no express language to the contrary, the default rule is that royalty calculations are not subject to those post-production costs.

Although "marketable product" jurisdictions generally agree that the lessee is responsible for the post-production costs that make gas marketable, there is some disagreement as to the point downstream from the wellhead that a marketable product has been achieved.

Oklahoma and Kansas hold that the implied duty to market requires the lessee to pay for post-production costs only until a product is in a condition in which it can be sold. Lessors still bear a proportion of costs for transportation to distant markets and to enhance an already marketable product..

Colorado and West Virginia hold that a marketable product has only been achieved when the product is both physically sufficient and delivered to the actual point of sale.

Though Ohio courts are not bound by the decisions of other state courts or of the regional federal district or circuit courts in which they sit, they routinely look to jurisdictions with established oil and gas jurisprudence for guidance on novel issues.

Accordingly, operators should expect that Ohio courts will weigh both approaches against Ohio law before ruling on the propriety of post-production cost deductions.

Fig. 4 shows the jurisdictions that have adopted the "at the well" theory and those that have adopted some variation of the "marketable product" theory. These competing rationales are at the forefront of Lutz v. Chesapeake Appalachia LLC, the case that certified the question of whether Ohio follows the "at the well" or "marketable product" approach to the Supreme Court of Ohio. If the court accepts the question, a ruling in early 2016 could change the landscape of Ohio law on this issue. A look at Ohio precedent that could influence that decision is useful.

Applying precedent

Determining if post-production costs are properly deducted from the production's value prior to calculating royalties should begin with the language of the oil and gas lease itself. Ohio courts have routinely considered leases to be contracts. They have emphasized freedom-of-contract principles, holding that the rights and remedies of the parties are governed by the language used in their agreements.

Ohio courts employ strict rules of construction when interpreting contract language. The court is required to give effect to the intent of the parties, which is presumed to be reflected in the language of the contract.

Words in leases are interpreted first according to their common meaning. Ohio courts frequently look to dictionary definitions in determining common usage of contract terms.

When the common meanings of words or phrases cannot be determined, they are given their technical meaning, unless a different intention is expressed in the contract. In these cases, Ohio courts frequently look to parol evidence-extrinsic evidence such as testimony from experts in the field-to explain the meaning of words with unique or technical applications.

Accordingly, the outcome in specific cases may depend on the individual parties' ability to provide appropriate support, for example parol evidence such as expert testimony, for their proposed interpretation of disputed lease terms.

Ohio courts are also required to give effect, whenever possible, to all words and phrases in a contract. They will generally shun proposed interpretations that render words or phrases superfluous.

If the court determines that the meaning of the term or phrase is not subject to a clear common or technical meaning but instead reflects an ambiguity that cannot be resolved by looking at the lease or to parol evidence, the language is usually construed against the drafter, frequently the lessee. It should be noted, however, that this language is frequently the subject of significant negotiations and joint drafting by both parties.

Schmidt v. Texas Meridian Resources

Until now, Ohio courts have not directly addressed which doctrine they will follow. Ohio case law reflects only one appellate-level decision addressing post-production costs in a lease containing at-the-well language. That decision failed to directly rule on the issue because of the specific facts before the court.

In Schmidt v. Texas Meridian Resources, lessors filed an action seeking an accounting of proceeds and reimbursement for alleged post-production cost deductions from royalty payments.

The leases in question contained several "proceeds" and "market value" royalty clauses, including some providing royalties be determined by the "market value…at the mouth of the well."

Despite finding authority from other jurisdictions instructive, the court ultimately evaluated the leases under traditional Ohio contract law. It determined that the phrases "market price," "prevailing market rate," "field price," "off the premises," and "at the mouth of the well" had no everyday meaning and were clearly terminology unique to the oil and gas industry.

As a result, the court looked to extrinsic evidence, including the expert testimony of a petroleum engineer who testified that the lease language reflected standard industry practice for deducting post-production costs when calculating royalties in Ohio and other jurisdictions.

Though the court appeared to favor the at-the-well rule, it noted that the lessee had failed to deduct post-production costs for 20 years.

The court concluded that, even if the at-the-well language of the leases would have otherwise provided for the deduction of post-production expenses, the agreement had been modified by the parties' course of conduct. The court, therefore, did not directly address the effect of the language of these lease provisions in its decision.

Royalty-clause provisions

The primary question for Ohio courts will be whether at-the-well language is sufficient to show the intent of the parties in allocating post-production costs between lessees and lessors.

As seen in Schmidt, because there is no controlling Ohio case law or guidance on these issues, Ohio courts are likely to look to traditional principles of contract interpretation and the reasoning employed by other jurisdictions in deciding post-production cost royalty disputes.

Several at-the-well jurisdictions with similar rules of contract interpretation as Ohio have determined that the generally-accepted meaning of the phrase at-the-well is unambiguous and refers to gas in its unprocessed state as it emerges from the wellhead.

For example, in Poplar Creek Development Co. v. Chesapeake Appalachia LLC, the US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, applying Kentucky law, held that the plain meaning of the phrase at-the-well is "gas in its natural state, before the gas has been processed or transported from the well."

That court permitted the lessor to deduct post-production costs before paying royalties.

In 2013, the Court of Appeals of Kentucky confirmed the result in Poplar Creek, holding that the phrase "market value at the well" is not ambiguous and permits the lessee to deduct reasonable costs of transportation and processing before calculating market value.

The Kentucky Court further noted that, far from being ambiguous, the phrase "market value at the well" was defined in Black's Law Dictionary as "(t)he value of oil or gas at the place where it is sold, minus the reasonable cost of transporting it and processing it to make it marketable."

Ohio courts may also be guided by prevailing case law that recognizes the generally accepted view that the phrase "at the well" has a long standing and unambiguous meaning in the oil and gas industry.

Decisions from Texas, Pennsylvania, Kentucky, North Dakota, Michigan, California, and the Fifth and Sixth Circuit Courts have all determined that the phrases "at-the-well," "at the wellhead," or "market value at the well" are clear and unambiguous, in general, and have established meanings in the oil and gas lexicon that permit the deduction of post-production expenses when determining the production's value.

Ohio courts, which are required to interpret technical terms in accordance with their particular trade or industry meaning, may find these decisions particularly persuasive.

Unlike other states, however, it would not be surprising for Ohio courts, at least initially, to require the parties to introduce parol evidence of industry usage because these issues are ones of first impression.

As seen in Schmidt, Ohio courts are hesitant to adopt "rigid interpretations . . . until such time as the issue has been considered by the Ohio Supreme Court . . . [or] other appellate jurisdictions [in Ohio]." Consistent with the court's holding in Schmidt, Ohio lessees and operators may be bound by their predecessors' past actions.

Even if the language of the lease supports the deduction of post-production expenses under the at-the-well rule, the court may view such terms as waived or modified by the parties' course of conduct if there was a long time during which the lessee or operator didn't deduct such expenses.

Conflicts of law

The various rationales offered for the "marketable product" theory, by contrast, are generally inconsistent with Ohio principles regarding the right-to-contract and contract interpretation. This theory may be viewed less favorably by Ohio courts than the at-the-well rule.

For example, the Supreme Court of Colorado's decision in Rogers v. Westerman Farm Co. and the Supreme Court of Appeals of West Virginia's decision in Estate of Tawney v. Columbia Natural Resources LLC, both held that "at-the-wellhead"-type language was ambiguous in isolation and therefore legally meaningless.

The courts made little attempt to look to the technical meaning of such terms or to parol evidence, as required under Ohio law, before construing the language against the drafter-lessee. These decisions also run afoul of Ohio's long-standing principle of contract interpretation that the court must give effect, if possible, to all the words in the agreement. If one construction of the contract would make words or provisions superfluous and another would give them effect, an Ohio court is generally bound to uphold the latter interpretation.

These decisions also have attracted criticism from leading authorities in the field, Williams and Meyers, for "treat(ing) the implied covenant to market as trumping the express provision limiting the calculation of the royalty to the gross proceeds measured at the mouth of the well."

Ohio recognizes several implied covenants in an oil and gas lease, including an implied covenant to market the production, but Ohio courts are very reluctant to override express contract terms in favor of implied obligations.

Typically, the prevailing view in Ohio that implied obligations cannot prevail over express contract terms.

The marketable-product theory also has been criticized as promoting the waste of oil and gas resources in violation of public policy. As a result of the theory's shifting of post-production costs to lessees, leases may stop producing in paying quantities sooner, resulting in the premature abandonment of recoverable reserves. This would potentially contravene Ohio's stated public policy of encouraging oil and gas production.

Practical implications

Whether certain post-production costs can be charged against a lessor's royalty interest is unsettled under Ohio law. The at-the-well rule, however, appears better aligned with established Ohio contract law and public policy than the marketable product rule. Ohio courts, however, place a great emphasis on the right to contract and will attempt wherever possible to give effect to the parties' written agreement.

Operators are advised to pay particular attention to lease language and to how that language and operator practices square with the parties' intent, as reflected in the lease. Demonstrating how lease language and practices align with the logic of the at-the-well rule, as well as Ohio's public policy in favor of development, is also advisable.

Bibliography

1. Bibikos, G.A., King, J.C., "A Primer on Oil and Gas Law in the Marcellus Shale States," Texas Journal of Oil, Gas, and Energy Law, 4 Tex J. Oil, Gas & Energy 155, 2009.

2. Broomes, J.,"Waste Not, Want Not: The Marketable Product Rule Violates Public Policy Against Waste of Natural Resources," University of Kansas Law Review, 63 U. Kan. L. Rev. 149, 2014.

3. Kuntz, E., Anderson, O., "A Treatise on the Law of Oil & Gas," LexisNexis, 2015

4. Martin, P., Kramer, B. "Williams & Meyers Oil & Gas Law," Fifth Edition, LexisNexis, 2013.

HIGH COURT WATCH

Many states have not yet considered or explicitly adopted either the "at the well" or "marketable product" approach or determined the boundaries of either. The issue of post-production costs is currently before the highest court in several states.

Ohio

The US District Court for the Northern District of Ohio certified the question of whether Ohio follows the "at the well" rule or the "marketable product" theory to the Supreme Court of Ohio on Apr. 1, 2015 in Lutz v. Chesapeake Appalachia LLC.

Kentucky

On June 11, 2014, the Supreme Court of Kentucky granted discretionary review to the decision in Baker v. Magnum Hunter Production Inc. and is poised to issue a decision as to whether it will follow the lower court's judgment adopting the "at the well" rule.

Texas

On Jan. 30, 2015, the Supreme Court of Texas granted a petition to review the Fourth District Court of Appeals' decision in Chesapeake Exploration LLC v. Hyder. The lower court ruled in favor of lessors and held that language providing for royalty "free and clear of all production and post-production costs and expenses…" and a overriding royalty "cost free" did not permit the deduction of post-production costs in determining the value of the lessors' royalty.

The authors

Greg Russell ([email protected]) is a partner and the Energy Group leader in the Columbus, Ohio, office of Vorys, Sater, Seymour and Pease LLP. He is also an adjunct professor at the Ohio State University Moritz College of Law, teaching a course on oil and gas law. He holds a law degree from Harvard Law School and a BA from Washington and Lee University.

Pete Lusenhop ([email protected]) is a partner in the Vorys Columbus office. He focuses his practice on oil and gas litigation. He holds a law degree from the Ohio State University Moritz College of Law and a BS from Miami University.

Steven Chang ([email protected]) is an associate in the Vorys Columbus office. He holds a law degree from Case Western Reserve University School of Law and a BA from Texas Tech University.