Winner’s curse: revisiting bidding challenges in the Gulf of Mexico

Michael R. Walls

Colorado School of Mines

Golden, Colo.

We are fast approaching the 50-year anniversary for the seminal paper entitled “Competitive Bidding in High-Risk Situations”, authored by E.C. Capen, et al. One of the fundamental findings of the Capen work was their notion of “winner’s curse”. Winner’s curse is a tendency for the winning bid in an auction to exceed the intrinsic value or true worth of an item. Because of incomplete information, emotions, or other factors regarding the item being auctioned, bidders experience significant difficulty in determining the item’s true intrinsic value. As a result, the largest overestimation of an item’s value ends up winning the auction. In the Capen work, the authors utilized data from the auctions for federal leases in the Gulf of Mexico and indeed found that many of the winning bids for leases were too high to allow for profit-making for companies.

It seems timely to re-visit more recent bid activities in the Gulf of Mexico lease sales and investigate some of the patterns in bidding behaviors. There is a rich set of data that has accumulated since the Capen, et al work that can provide both insights and analytics to better support bid decision making in the Gulf of Mexico.

Results from recent lease sales

For purposes of this study, the focus is on the deep-water area of the central region of the Gulf of Mexico. Deep-water is defined as water depths greater than or equal to 400 m (1,312 ft). For a view of the recent bid data in the Gulf, we examine the period 2000 through 2018 utilizing data from the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM).

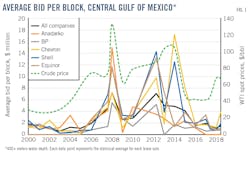

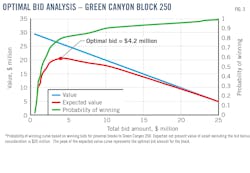

Bid amounts and bid activities have varied dramatically over the recent lease sales in the Gulf of Mexico. Fig. 1 shows the Average Gross Bid in dollars per nine-square mile block for lease blocks in the deep-water central region of the Gulf of Mexico for a representative group of firms. This same figure shows West Texas Intermediate spot prices over that same period. As expected, bid amounts are positively correlated with prices.

The statistics compiled for Average Gross Bid includes both winning and losing bids. Each data point on the graph indicates the statistical average for a specific lease sale for an individual company or all companies. For the “all companies” category shown on the graph, we observe significant differences in average gross bid per block over this 18-year period. Note that in 2003, average bids were $599,000 per block, in 2008 that value sharply increased to an average of $7.2 million per block and have subsequently decreased to $1.5 million per block in 2017.

Overbidding challenges

The extent to which firms overbid is of particular interest in these data, since significant overbidding can lead to capital destruction and low rates of return on acquired blocks. “Overbid” can be viewed in a number of different ways. In the case of multiple bids for a single block, the overbid is defined as the difference between the highest winning bid and the second highest bid. In the case of a sole bidder for a block, which is a highly frequent occurrence, it is the difference between the single bid and the BOEM’s designated minimum bid or its post-bid Mean Range of Values (MROV), which serves essentially as the minimum bid set after the bid round is complete for selected blocks. Of course, to win a block an operator’s bid will have some amount of overbid; the challenge is to minimize the overbid amount.

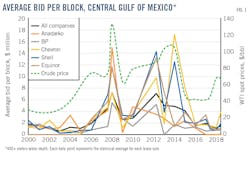

Figure 2 shows a plot of the average competitive overbid per block for all firms (black line), as well as the representative firms over the period 2000 to 2018. The overbid amounts shown in Figure 2 represent the “competitive” overbid amounts, that is, when there was more than one bidder for a given block. Note that the average competitive overbid for all companies in Lease Sale 251 in 2018 was about $2.0 million per block. However, the average overbid for all companies in Lease Sale 227 in 2013 was $12.8 million per block. Moreover, we see from Fig. 2 that in our representative group of firms that there are overbids that range considerably higher than the average overbid amount for the “all companies” category. The empirical data suggests a high degree of volatility with respect to bidding behaviors, as well as overbidding.

There are numerous examples of significant overbidding behaviors in recent leases sales in the Gulf of Mexico. In terms of overbids on individual blocks, the highest overbid to date in the Gulf of Mexico was Statoil’s (Equinor) $126 million overbid for a single block in Lease Sale 222 in 2012. Other examples of notable overbids were Shell Oil’s $55 million overbid in Lease Sale 222 in 2012 and Anadarko’s $52 million overbid in Lease Sale 213 in 2010. These represent only a few examples of significant overbids that have occurred in the Gulf over the last 18 years. Since 2010, the total overbid amounts for all firms in the Gulf is approximately $3.2 billion and the total competitive overbid amount for that same period is approximately $2.0 billion.

Another way to characterize these findings is in terms of the “overbid rate”. This measure represents the percentage of overbid as compared to the next closest bid. Since 2010, the average overbid rate for cases where there were two or more bidders was slightly greater than 100% or more than double the next closest bid. In the case of sole bidders, the average overbid rate was almost six times the minimum acceptable bid set by the BOEM. Given the continued pervasiveness of overbidding in the Gulf of Mexico, firms are significantly challenged to analyze bid decisions in a way that reduces overbidding and minimizes the likelihood of “winner’s curse”.

Traditional bid model – expected value analysis

The traditional expected value (EV) analysis model for bid decisions provides a forward-looking approach to estimate the optimal bid amount on a firm’s block of interest. The optimal bid amount for a “focal” block of interest is a function of (1) the likelihood of winning the block at alternative bid amounts; and (2) the estimated net present value of the block. The probability of winning curve is estimated from the empirical data in the region of the focal block of interest. The “proximal” blocks selected to compute the probability of winning curve can be geographical and/or geologically proximal to the block of interest. The key issue here is that the selection of blocks to compute the probability of winning curve should represent blocks where the past bidding behaviors are anticipated to be similar to the focal block of interest – typically including some combination of geological similarities, competitive players, and/or geographical location.

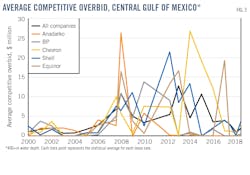

Fig. 3 shows an analysis of the Green Canyon 250 block from Lease Sale 247 in March of 2017 utilizing the expected value approach. Note that in this analysis the Probability of Winning line (green) is derived from the prior winning bid amounts in the geologically and/or geographically relevant area of the Gulf. It is simply the cumulative distribution of winning bids associated with the proximal block selections that are relevant to the focal block of interest, Green Canyon 250. Let’s assume the net present value of the Green Canyon 250 block is estimated to be $30 million. This is the net present value of the asset based on the reserves and economic analysis, but excluding the bid bonus consideration. The Value line (blue) represents the value of the asset at alternative bid amounts which is simply the firm’s estimate of the net present value minus the bid amount. The Expected Value line (red) in the graph is simply the product of the probability of winning at a selected bid amount and the asset value minus the bid amount.

The peak or turnover point of the expected value line represents the optimal bid when the firm is attempting to maximize the expected monetary value associated with the block. So, lowering the bid amount will increase the overall value of the asset but decrease the probability of winning, thereby lowering the overall expected value. Similarly, while raising the bid amount will increase the probability of winning, it will reduce the overall value of the asset; again, leading to a lower expected value. The optimal bid shown for Green Canyon 250 is $4.2 million. There were two bids on this block during Lease Sale 247; the winning bid was $5.3 million (Exxon) and the losing bid was $3.2 million (EnVen).

This traditional approach to identify the optimal bid for a block of interest combines the historical view of bidding activities and behaviors with a forward-looking approach that incorporates the firm’s assessment of the value of the asset. The critical aspect of the traditional bid model is a sound estimation of the probability of winning curve and the selection of previous bid activities that best represent the expected activity on the focal block of interest.

Advances in bid decision making–a data-analytic approach

The field of data analytics represents the intersection of information technology, statistics and business. One of the primary goals of data analytics is to increase efficiency and improve performance by discovering patterns in data. At the heart of it, data analytics is the process of analyzing raw data to find trends and answer questions. Generally, this process begins with descriptive analytics, which aims to answer the question “what happened?” The tools utilized in data analytics include classical statistics as well as econometric methods. The rich data set provided by a long history of bidding activities in the Gulf of Mexico is well-suited for application of these analytic methodologies and can provide meaningful decision support when managers are faced with competitive bidding situations.

Estimating the probability of multiple bids

In statistics, logistic regression is used for prediction of the probability of occurrence of an event by fitting data to a logistic curve. It is a generalized linear model used for binomial regression. Like many forms of regression analysis, it makes use of several predictor variables that may be either numerical or categorical. In the context of bidding analysis, this form of regression is designed to capture the impact of predictor variables that may influence the likelihood that a focal block of interest receives multiple bids. For example, the probability that a focal block of interest will receive a bid might be predicted from knowledge of the focal block’s attributes such as proximal competitive bidding behaviors, offset production, water depth, a block that is newly available, estimated MROV, magnitude of offset bids, consortium bidding behavior, etc.

The logistic regression model is used when the dependent variable is not continuous but instead is dichotomous in nature and has only two possible outcomes, 1 or 0. In the case of offshore bidding, the predicted outcomes would be “Bid” versus “No Bid”. Regular regression models are not optimal in such cases because the predicted value should be constrained between 0 and 1. It also violates the assumption that the variable is normally (single peak) distributed, since a 1/0 variable by definition has a binomial distribution (double peak). The binary logit model represents a particularly effective application to the analysis of bid activity.

The goal of logistic regression is to correctly predict the category of outcome, multiple bids versus less than 2 bids for a focal block of interest, for individual cases using the most parsimonious model. This pooled-style regression model combines all the block attributes and bidding behaviors over the last eight lease sales in the Gulf of Mexico.

Estimating the winning bid amount

Multiple linear regression allows us to test how well we can predict a dependent variable on the basis of multiple independent variables. For example, in a focal block analysis, proximal block attributes such as proximal bid activity, oil price, estimated MROV, offset production, multiple bids, consortium bids, expected number of bidders, etc. are utilized to assist in the prediction of the winning bid amount. The multiple linear regression approach helps us understand how these measures (the independent variables) relate to the predicted winning bid amount (dependent variable) on the focal block of interest.

The general form of a multiple regression model is as follows:

Y = β0 + β1x1 + β2xβ + β3x3 + . . . + βnxn + ε

where, Y is the dependent variable (winning bid amount) and xi are the independent variables, as noted above. Parameters β1, β2, β3, and βn, are referred to as partial regression coefficients and β0 is the regression intercept.

The goal of the multiple linear regression models is to estimate the winning bid value on a focal block of interest using the most parsimonious model. To accomplish this goal, we develop a regression model that includes all predictor variables that are useful or statistically significant in predicting the response variable. This type of pooled-style regression model also combines all the block attributes and bidding behaviors over the last eight lease sales in the Gulf of Mexico.

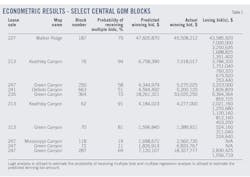

Table 1 shows a sample of selected blocks from recent Gulf of Mexico lease sales. The table indicates the lease sale, block name and number, the statistical predictions of the probability of receiving multiple bids and the predicted winning bid amounts, as well as the actual winning and losing bids, where applicable.

Utilizing block attributes and prior competitive bidding behaviors from the prior eight lease sales, the predictive and explanatory power of the regression models is robust. For example, in Walker Ridge 187 and Keathley Canyon 76, the predicted bids are well in line with the actual winning bid on each of these blocks. In addition, the predicted Probability of Receiving Multiple Bids is relatively high on each of these blocks that had multiple bids. Conversely, Green Canyon 364 and Green Canyon 287 had significantly lower predicted winning bids than the actual winning bid amounts. The conclusion here would be that the winning bidders significantly overbid on each of these blocks. Finally, note that on blocks that had sole bidders (Mississippi Canyon 118 and Green Canyon 72), the predictive model’s estimates of the Probability of Receiving Multiple Bids are very low values, consistent with the actual bidding outcome.

The approach utilizes a large data set to provide significant decision support in terms of understanding competitive bid behaviors and how it may impact bidding activity on blocks of interest in a competitive bid sale. This bid-setting method can improve the chance of winning blocks of interest while at the same time reduce the chance and amount of overbidding.

Conclusions

The challenges and pitfalls of competitive bidding in the Gulf of Mexico highlighted by Capen, et al nearly 50 years ago still resonate in the industry. Significant overbidding is still pervasive in the Gulf of Mexico and firms are at risk of the dreaded winner’s curse effects that result from these actions. Increasing uncertainty as the industry moves into deeper and more challenging operating environments further complicates these decision problems and motivates decision makers to utilize tools that can improve their bid decision making process. The traditional expected value bid models and the more advanced data-analytics tools can significantly improve the overall quality of bid decisions for firms operating in these competitive bidding environments.

References

- Capen, E.C., Clapp, R.V., and Campbell, W.M. (1971). Competitive Bidding in High-Risk Situations, Journal of Petroleum Technology, June 1971, pp. 641-653.

- Lohrenz, J. (1987). Bidding Optimum Bonus for federal Offshore Oil and Gas Leases, Journal of Petroleum Technology, September, 1987, pp. 1102-1112.

- Rothkopf, M. & Harstad, R. (1994). Modeling Competitive Bidding: A Critical Essay, Management Science, Vo. 40 No. 3, Interfaces, March 1994, pp. 364-384.

- Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), U.S. Department of Interior, Gulf of Mexico Lease Sale Information, 2000-2018.

The author

Michael R. Walls ([email protected]) is a Professor Emeritus in the Division of Economics & Business at the Colorado School of Mines. He has served as a professor and director of the Division of Economics and Business where he focused on strategic decision making and risk management, particularly as it relates to the petroleum industry. He has published extensively in the areas of decision analysis and risk management. He holds a BS in geology and a MBA in finance and a PhD in management from the University of Texas at Austin. Walls has advised in the areas of risk analysis, corporate risk policy, and strategic planning to numerous companies in the petroleum industry.