Why higher oil prices are inevitable this year, rest of decade

HUBBERT REVISITED—4

The stubborn refusal of oil prices to drop in recent months has amplified doubts regarding the adequacy of near-term oil supplies and the long-term outlook for crude oil prices. Within the first 6 months of 2004, average spot market prices increased by more than $5/bbl (see table).

Given the International Energy Agency's projection that demand will increase by 3 million b/d by yearend1 and the limited availability of excess capacity,2 additional price increases clearly are inevitable.

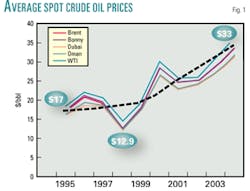

The most recent escalation in oil prices originated in 2000 but was temporarily obscured by the economic rollback following the events of Sept. 11, 2001 (Fig. 1). By yearend 2002, however, the upwards spiral was reestablished, and spot market prices reached new highs not seen in years.

The key question is: Are these high prices a reflection of temporary production disruptions and political instability, or are they indicators of a long-term trend towards sustained high crude oil prices?

Given the complex issues associated with finding and developing substantial new production capacity within a limited number of years, there is little ground for optimism regarding a return to an era of inexpensive oil prices.

Short-term drivers

Global geopolitical factors have always played a role in determining the level of "security" in the oil markets and therefore have an important impact on oil prices.

The regional conflicts in the Middle East, home to over 65% of the world's oil reserves and 30% of global oil production, have had a particularly crucial role in this regard.

The unresolved fall-out from the Afghan war, coupled with the Iraq crisis, Kuwaiti fundamentalism, a US embargo on Iran, and terrorism in Algeria and Saudi Arabia, have augmented the violence in the Middle East already exacerbated by endless years of Israeli raids and military occupations.

These geopolitical realities have inhibited upstream exploration and development within the Middle East and resulted in a scarcity of new production increments. This history of violence also has threatened the continuity of existing supplies from parts of the region, which in turn created reliability and market-speculation issues and premiums.

The geopolitical roots to the Middle Eastern conflicts are now deeply seated, and their near-term resolution does not appear to be imminent. Therefore, their fallout on oil prices is likely to be enduring, and their impact on price volatility could persist for years.

In addition to the Middle Eastern tensions, labor turmoil in Nigeria and political clashes in Venezuela also have created new anxieties in oil markets. Given the tribal and ethnic issues associated with the Nigerian unrest and the class tensions within the political conflict in Venezuela, these turmoils also are unlikely to be resolved in the near future.

In previous years, it had been assumed that the Russian political establishment would relieve the scarcity of oil supplies in global markets by expanding Russia's oil sector through foreign investments and liberalizing the management of its industry. In reality, these trends have not evolved, and the strong-arm policies of the Russian government towards OAO Yukos have clearly signaled a return to a highly centralized and politically managed oil industry (see related story, p. 20).

In parallel with these developments, pipeline projects from the Caspian Sea region and Siberia to the Mediterranean and the Pacific have been slow to materialize. Current estimates of timing and volumes suggest that in any case they would not offset the accelerating production declines in North America and the North Sea while accommodating increasing demand throughout the world.

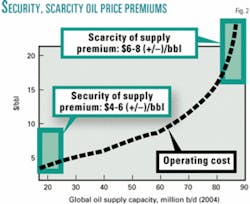

The combined effect of all these short-term factors has been a increase in the "security of supply" and the "scarcity of crude" premiums (Fig. 2). These premiums used to be sporadic factors in the oil marketplace but now appear to have become long-term fixtures, unlikely to dissipate for years to come.

Outlook for 2004

The Energy Information Administration in its July Short-Term Energy Outlook and the IEA in its July Monthly Oil Market Report estimate that global oil demand will increase by 3.3 million b/d and 2.9 million b/d, respectively, between the second and fourth quarters of 2004. The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries in its July Monthly Oil Market Report forecast an increase of 3.9 million b/d over this same time frame.

Meanwhile, excess capacity is largely in heavier OPEC crudes and is limited to an additional 1 million b/d of sustainable production, according to EIA. Reports of "surge" capacity are unreliable because such surges in fact create severe and often irreversible damage to mature oil wells and are unlikely to be recommended by professional operators. At a minimum they would drive costs upward in the immediate future through extensive remedial recompletions or additional artificial lift investments.

New OPEC capacity is scheduled to come online within the second half of 2004 that may reduce the gap between supply and demand.

On the other hand, this is a limited volume from plants and facilities under commissioning and originally was scheduled to replace declining capacity in any case.

In view of these realities, oil companies will need to build up inventories during the third quarter in anticipation of fourth-quarter shortages. This is aggravated by the fact that the July EIA report estimated that US oil inventories are below normal levels for this time of year.

The oil companies' dilemma will be whether to build inventory at current high prices, which could be exacerbated by continued high levels of liftings, or to delay liftings in the hopes of a clement winter, or to build inventory with the intent of passing on price premiums to the products markets. Either way, the "security" and "scarcity" premiums will weigh heavily on the markets during the balance of 2004, and oil prices can only rise to higher levels.

Long-term fundamentals

In the longer term, crude oil prices are destined to continue to escalate through the end of the decade.

On one hand, the global concentration of oil and gas resources within turbulent OPEC countries and Russia provides no relief from the security-of-supply issues. On the other hand, the future resources themselves may not be as abundant or readily available for development as assumed by organizations such as EIA and the US Geological Survey.

In fact, the issue of future oil resource estimates is a hotly debated topic in its own right. On one hand, USGS and EIA hold that there is an abundance of proven oil reserves. When coupled with anticipated reserves "growth" and "yet to find" resources, they place the remaining global oil resources at just under 3 trillion bbl.3

As a consequence, EIA's "reference case" for 2025 forecasts global production will exceed 120 million b/d while oil prices will rise to $35/bbl, in 2003 dollars. OPEC production is expected to more than double to over 61 million b/d from 29 million b/d, while non-OPEC production increases to 64.6 million b/d from 50 million b/d.

In fact, EIA estimates of OPEC reserves and resources total 1.666 trillion bbl of oil, almost double OPEC's already contested proven reserves of 870 billion bbl. EIA further estimates non-OPEC reserves and resources to be four times their currently reported levels, totaling 1.269 trillion bbl instead of the current 396 billion bbl of proven reserves.

Several energy analysts have concerns regarding the credibility of the USGS and EIA estimates.4-7 Their belief is that global reserves are in fact significantly overstated and that global oil production may have peaked or is approaching its peak capability on a worldwide basis, let alone be in a position to rise to over 120 million b/d.2-5

Long-term realities

In reality, even if the USGS and EIA resource estimates are technically feasible, their conclusions regarding future oil production capacities are not straightforward and cannot be reliable.

Regardless of global economic growth and the demand for energy, additional oil supplies require massive and urgent investments with supportive national policies within OPEC and major non-OPECoil exporting countries. There is no evidence that these policies and hence the investments are occurring on the required scale anywhere in the world.

Furthermore, if a rapid increase in global oil production were to occur, it would result in an accelerated depletion of proven and existing resources. This would require an even more rapid and coordinated resource and capacity replacement program in order to avoid a shortage of energy supplies in the energy markets. Such coordination within and across energy sectors would be a very challenging task within countries, let alone across national boundaries.

Finally, there are good technical reasons to believe that the remaining oil and gas resources are in fact of much lower quality and profitability than the global reserves now being consumed. In fact, with rare exceptions, hardly any investor-friendly policies have been articulated in recent years by any of the nations holding major oil and gas resources.

A good illustration of this trend is supergiant Kashagan field, discovered in Kazakhstan in 2000.8 The field was reported to have 38 billion bbl of OOIP, but recovery, including gas reinjection, is now estimated to yield only 13 billion bbl of reserves. First oil is not anticipated until 2008 at an initial production rate of 75,000 b/d. This is expected to rise to 450,000 b/d by the end of the first phase of development and, depending on the execution of unspecified future plans, maximum capacity may rise to 1.2 million b/d. The current estimate for full field development already stands at $29 billion.

Clearly, even a giant field of Kashagan's scale, in spite of the long-term outlook for high oil prices and limited supplies, is proving too complex a technical and political challenge for the rapid exploitation of its resources. At the current rate of development, it cannot reach its presumed full production potential until well into the next decade.

In fact a global strategy of accelerated resource depletion that reduces the life of proven oil reserves while undermining world oil prices can hardly be in the interest of resource-rich countries. In the case of Kazakhstan, the government may have deep-seated reservations regarding the depletion of a field such as Kashagan, at a maximum rate of 438 million bbl/year, while serious reservations regarding ultimate oil and gas recovery remain in contention.

It would require major global changes in upstream exploration and development policies throughout the industry before changes in national policies are likely to occur. None of these changes appears to be occurring in OPEC, Mexico, Russia, or the other Central Asian countries, and Kazakhstan is unlikely to be the exception.

Oil price forecast

In conclusion, it is realistic to assume that while there will continue to be future oil discoveries and developments, the majority will be smaller, complex accumulations. Consequently, their finding and development costs will be higher than past experience. Furthermore, many will be grassroots developments or include major costs for replacement and refurbishment of existing plants and infrastructure. This will add to costs of maintaining capacity, which also will be high.

To the extent that global transportation infrastructure will require new pipelines, power plants, storage, and terminal facilities, these costs also must be reflected in future oil prices. In the case of Canadian extra-heavy oils, allowance must also be made for the 45-50% bitumen yield from crude distillation, which has little commercial attraction.

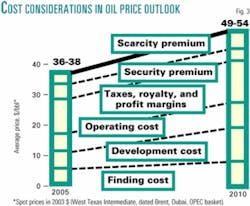

These cost considerations are summarized in Fig. 3 and need to be factored more fully into the EIA's long-term oil pricing outlook.3 Given its forecast of global oil demand rising to over 91 million b/d 2010 from 79 million b/d in 2003, significant increases in real oil prices would be inevitable.

Even EIA's high-price case of $33/bbl in 2010 is questionable, given that no major oil discoveries or expansion projects are now in sight, and it would take years of investments to replace declines, let alone adding new net increases in production capacity.

While a price forecast of $36-38/ bbl by 2005 is now almost inevitable, oil prices at $49-54/bbl by 2010 are far more probable than the EIA's estimate of $33/bbl for 2010.

To assume lower long-term prices, under the current international political and economic outlook, would be less than prudent for private sector industry and investors.

To ignore the probability of much higher prices than those projected by EIA and others3 would be unrealistic and misleading in terms of ensuring the availability of adequate energy supplies needed to maintain economic growth throughout the world.

References

1. International Energy Agency, Monthly Market Report, May 2004.

2. Wall Street Journal, July 14, 2004.

3. Energy Information Administration, International Energy Outlook, April 2004.

4. Zagar, Jack, and Campbell, C.J., "The End of Cheap 'Conventional' Oil" Energy Forum Conference, Rice University, Houston, May 19, 2000.

5. Zittel, Werner, and Schindler, Jorge, "Future World Oil Supply," International Summer School on the Politics & Economics of Renewable Energy, University of Salzburg, July 15, 2002.

6. Bakhtiari, A.M. Samsam, "Middle East oil production to peak within next decade," Oil & Gas Journal, July 7, 2003.

7. Simmons, Matthew R., "Global Crude Supply: Is the Oil Peak Near?", World Energy, Vol. 7, No. 1, 2004.

8. Shell in the Middle East magazine, No. 26, July 2004.

This is the fourth in a series of six articles revisiting the peak oil debate.

The author

Sadad al-Husseini retired from Saudi Aramco on Mar. 1 as executive vice-president and a member of its board of directors. He joined Aramco in 1972, and his assignments have included various senior executive posts in its oil and gas exploration, production, and development operations. He was a special representative of the kingdom of Saudi Arabia in its natural gas negotiations from 2000 to 2002. Al-Husseini was a member of the Saudi Aramco management committee from 1992 until his retirement and was elected a member of its board in 1996. He also was a member of the Consolidated Saudi Electric Co. board during 2000-03 as well as holding other board positions in joint ventures and subsidiaries of Saudi Aramco. Al-Husseini graduated from the American University of Beirut with a BS in geology in 1968. He obtained his MS in 1970 and PhD in geological sciences in 1973 from Brown University (distinguished graduate school graduate). He is an honorary member of the American Institute of Metallurgical, Mining & Petroleum Engineers and the Society of Petroleum Engineers.