India upgrades exploration policy, seeks international investment

Ripunjaya Bansal

National Institution for Transforming India (NITI) Aayog

New Delhi

India's upstream sector needs private investment to expand exploration and expertise in its deepwater and ultra-deepwater areas, which account for a third of the country's discoveries. A progressive and practical exploration policy should expand India's upstream sector.

The country's New Exploration Licensing Policy (NELP) has launched nine rounds to date, with the last held in 2010. A close look at the data shows that NELP has largely been unsuccessful in meeting its objective of increasing production and attracting international investors. This article elaborates on the reasons for this lack of progress and provides suggestions on remedial actions required to attract global exploration companies, with the goal of enhancing India's domestic hydrocarbon resource development.

India's upstream sector opened to private investment in 1999 with NELP's first round. The Government of India realized the need to increase domestic crude oil and natural gas production as the country's two state-run firms Oil and Natural Gas Corp. (ONGC) and Oil India Ltd. (OIL) were struggling to do so. But NELP was initially biased toward safeguarding government interests, which affected the policy's proper implementation. The government has since sought to address NELP's shortcomings.

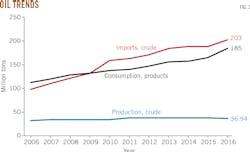

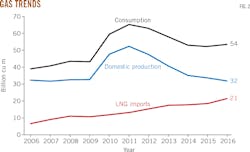

India is largely dependent on imports to meet its crude requirements, making it vulnerable to supply disruptions. The country has diversified its oil supply sources over the last 2 years, taking advantage of the sharp decline in crude prices to switch out of long-term contracts with Middle East suppliers when possible in favor of African spot purchases. Nigeria became India's top supplier in June 2015, but Saudi Arabia quickly regained the position in October that same year.

The share of imports in India's total oil consumption soared to 81% in 2015-16 from 34% in 1999-2000, and the International Energy Agency (IEA) has predicted this could increase to 90% by 2040.1 Domestic production has been almost static (Fig.1 and Fig. 2).

Pre-NELP licensing

In the late 1970s, India's blocks were awarded only to ONGC and OIL for exploration. The government nominated NOCs upon formal expression of interest. From 1980-95, 28 exploration blocks were offered to private companies under pre-NELP licensing, but ONGC and OIL retained rights of participation after discovery of hydrocarbons.

Petroleum mining leases (PML) also were offered pre-NELP in 1992 and 1993 to private companies under the condition that a joint venture (JV) be formed with an NOC. Part of NELP's 1999 launch was the Indian government's desire to reduce oil and gas imports 10% by 2022, a goal which will require aggressive production increases to meet based on 2014-15 levels.

Rollout, new discoveries

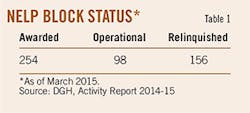

NELP was formulated in 1997-98 and came into effect in 1999, opening Indian fields to foreign direct investment (FDI). The new policy provided a level playing field for state-run, private, and other international companies to be awarded blocks through competitive bidding. In nine bid rounds to date, NELP has awarded 254 blocks to national, private, domestic, and foreign companies, generating $25 billion of investments as of March 2015.2

During 2000-05, new discoveries occurred on a monthly basis. Reliance Industries Ltd.'s KG D6 gas field ranked as the world's largest discovery in 2002. But while NELP discovery figures are promising, the program has so far not achieved its primary objective, increasing domestic production.

NELP facts, figures

Aside from a handful of private companies, NELP has been unsuccessful in attracting major outside investment. Table 1 shows the total number of blocks awarded, operational, and relinquished under NELP. The 98 operational blocks seem encouraging, but only 9 blocks are producing, providing a clearer picture of NELP's effectiveness.

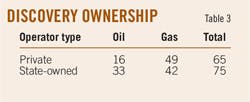

Reliance Industries, ONGC, and Gujurat State Petroleum Corp. (GSPC) have made the bulk of the discoveries under NELP (Table 2). Reliance has 54 of 65 (83%) oil and gas discoveries among private firms. ONGC and GSPC account for 97.4% of discoveries among NOCs. The absence of supermajor exploration companies on this list shows that NELP has attracted few independent oil companies. Public sector companies continue to dominate India's upstream sector (Table 3).

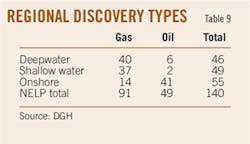

The rate at which discoveries are brought to production raises doubt as to NELP's efficiency. Out of 140 oil and gas discoveries made under NELP, only 16 (11 oil and five gas) are producing (Table 4). Reliance is the only private company producing. Niko Resources Ltd.'s two mature gas discoveries in Gujarat have ceased production. NELP production accounted for less than 1% of India's 37 million ton total in 2015-16 (Table 5).

Oil production from the RJ-ON-90/1 Block in Rajasthan, a JV between Cairn India Ltd. (70%) and ONGC (30%), accounted for 23% of India's 2015-16 domestic production. Cairn India operates the block and produces from the Mangala, Bhagyam, Aishwariya, Raageshwari, and Saraswati fields. Cairn acquired the exploration interest from Royal Dutch Shell in 2002, the major having acquired its rights pre-NELP in May 1995. Reliance's KG-DWN-98/3 (KG D6) field produces more than 99% of gas from NELP developments (Table 6). The KG D6 gas field is the largest field developed under NELP and its gas production declined 78% from 2010 to 2015.

Exploration efforts

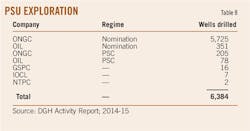

Reliance and Focus Energy Ltd. are India's most active domestic exploration companies (Table 7). Cairn India is the leading foreign driller, but most of its activity is isolated to RJ-ON-90/1. Niko Resources and British Gas Exploration & Production (India) Ltd. have also drilled exploration wells (Table 8).

Public sector undertakings (PSUs) have drilled 283 wells under NELP (Table 9). ONGC drilled most of these. Tables 8-10 show the lack of exploration efforts and capital investment in India's oil and gas sector. From NELP's inception through March 2015 a total of 6,959 exploration wells have been drilled. By comparison, in 2012 alone roughly 48,000 and 13,000 exploration wells were drilled in the US and Canada, respectively.

Cost recovery disputes

NELP's production sharing contract (PSC) allows operators to recover exploration and development costs. The government's percentage is committed in the operator's bid, and it increases incrementally with improved production throughout the development period. The policy was designed for an operator to share a larger percentage of its revenue during early development phases with smaller increments added as the field matures.

In NELP VI, some operators misinterpreted this provision, resulting in disproportionate government shares in profitability. Operators viewed the variable government share for some contracts as a disincentive for increased production from KG D6. The issue has been sorted out, but the conflict demonstrated the importance of clearly defined incentives.

Price, marketing controversy

NELP VII introduced more controversy, with conflicting statements in the PSC's Article 21 concerning natural gas. The provision allowed operators to market produced gas and simultaneously stated that gas would be sold per the government's policy for utilization among different sectors. The government instituted price mechanisms to reconcile the conflict, establishing uniform prices for NELP gas across different sectors and a distinction between the price at which gas is sold and the value that formed the basis for calculating government revenue. India's government made the distinction between gas price and value to safeguard its share of royalty. The government later clarified that its share of revenue would be calculated on the basis of either price or value, whichever is higher, making the distinction irrelevant. These amendments were intended to address NELP's problems, but ultimately added unnecessary layers of complexity.

Production, revenue sharing

Revenue sharing's inactive status during the cost recovery phase has led to conflicts in managing upfront costs. Several operators, including Reliance, have been accused of inflating costs with the intent of delaying the government's profit sharing. The government is working to resolve this issue, but in May 2016 also introduced the Discovered Small Field Policy (DSFP), offering 67 marginal fields held by ONGC and OIL spread over nine sedimentary basins for outside investment.

India's government introduced the Hydrocarbon Exploration Licensing Policy (HELP) as part of DSFP, providing a single license for conventional and unconventional hydrocarbons, including oil, gas, shale, coalbed methane, tight gas, and gas hydrates. HELP gives operators the freedom to market produced oil and gas domestically through a transparent bidding process, and alleviates the conflicts experienced in early NELP licensing.

HELP also does away with cost recovery based on pretax investment multiples and simplifies the revenue sharing model. Exploration periods are extended to 8 years for onshore and shallow-water areas and 10 for deep and ultra-deepwater blocks. Under NELP, these periods were 7 and 8, respectively. HELP is a progressive step toward practical resource development.

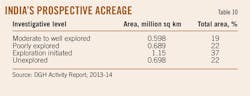

Lack of private interest

Only 19% of India's 3.14 million sq km of sedimentary basins are moderately to well-explored. Potential reserves numbers suffer from a lack of data and accurate estimates, and companies often hesitate to commit to profit-revenue splits in advance of bidding.

India's 2,000-m deepwater eastern offshore area is its most prospective region, which accounts for 43% of its total gas discoveries (Table 10). Technical difficulty and higher costs deter widespread exploration, and the lack of supportive market prices further reduces the economic viability of India's deepwater. The obstacle of fewer data can be overcome with aggressive exploration, but India's policies need improvement to attract more international investment.

Data, exploration

Operators require more subsurface data to commit to finding and developing resources in India's unexplored basins. India's policy should remove operator work requirements until the industry has basic geological and geophysical data to survey. Policies should be clear enough to avoid disputes and the government should abide by contractual norms to ensure private investors of project continuity.

India's policies must focus on increasing exploration activities across all 26 sedimentary basins. Expanding exploration efforts-2D, 3D, and drilling-will alleviate uncertainties in India's subsurface.

India plans to replace NELP with the Open Acreage Licensing Policy (OALP), allowing companies to bid year round on prospective acreage instead of waiting for an annual government-sanctioned bidding round. OALP has not launched, and its success would depend on geological data. India's government is forming a National Data Repository (NDR) that will house exploration and production data. The government has already begun assessment of India's sedimentary basins, a priority given data's place as a precondition for the OALP.

References

1. Government of India, Ministry of Petroleum & Natural Gas, "Petroleum Planning & Analysis Cell," October 2016, www.ppac.org.in.

2. Government of India, Directorate General of Hydrocarbons, "Petroleum Exploration and Production Activity Report 2014-15," March 2016, pp. 212.

The author

Ripunjaya Bansal ([email protected]) working at NITI Aayog, Government of India, where he developed the India Energy Security Scenarios (IESS) 2047 V2 project. He has a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from Thapar University, Patiala, India. He is a member of the Society of Automotive Engineers (FSAE).