Hydrocarbon reservoir potential estimated for Iraq bid round blocks

Editor’s note: This article contains material for which attribution is insufficient from Wood Mackenzie’s Iraq Country Overview published by Wood Mackenzie Upstream Service in December 2010.

Muhammed Abed Mazeel

RWE Dea AG

Hamburg

Iraq's fourth bid round is scheduled for April 2012, as announced in May 2011.

The round will be the first to put forth exploration contracts rather than the technical contracts offered in the previous three rounds.

Originally 46 companies qualified for this round, but this is split into operating companies and nonoperating companies that can compete on contracts but only as a partner in a combine that is led by an operating company.

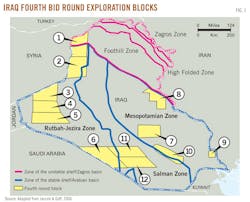

Twelve areas are on offer covering a combined 81,700 sq km with the blocks having a mix of oil and gas prospectivity (Table 1). However, many of the blocks contain oil and gas shows, some of which are close to previously discovered fields. Eight of the 12 blocks are situated in western Iraq along the borders with Syria, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia (Fig. 1).

Iraq's western and southwestern desert is estimated to have high hydrocarbon potential. Thousands of kilometers of 2D seismic data have been shot, and the state Oil Exploration Co. (OEC) discovered several fields.

In the 1990s, ONGC Videsh Ltd. of India operated the former Block 8 in the western and southwestern desert and drilled seven exploration wells. OVL estimated that the block, including Abu Khaima field, has the potential to produce up to 300,000 b/d. The Ministry of Oil has renegotiated the previous contract under the new exploration service contract and may renegotiate it again under the proposed petroleum law.

New contract terms are intended to attract international oil company investment. The area of each exploration block ranges from 900 sq km to more than 9,000 sq km (Table 1). Two blocks border Syria, three are near Syria and Jordan, three are near Saudi Arabia, and two lie along the Iran border. All contain numerous undrilled prospects.

Only four exploration wells have been drilled on the blocks, and the seismic coverage is old and of poor quality. OEC had planned to drill more than 300 exploration and appraisal wells in the western and southwestern region, but it is highly unlikely that such a program could have been achieved.

In the west, northwest, and southwest of Iraq are the Abu Khaima, Ekhaidar, Khleisia, Salman, and Samawa oil discoveries, the Akkas and Diwan gas-condensate discoveries, 300 prospects, and a wide number of upsides.

The objective of this article is to identify and evaluate the petroleum systems of prospects and leads, calculate the potential reserves, and evaluate the hydrocarbon potential and economics of the 12 blocks from the author's synthesis of books, articles, and published ministry data.

Exploration leads were identified by the author and OEC using the seismic data available over each block. The seismic data were tied into wells on or near the blocks. Geology and petrophysical analyses of wells, fields, and nearby fields and wells were evaluated. Potential reserves were then estimated for each lead.

Estimated exploration potential

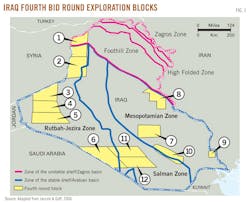

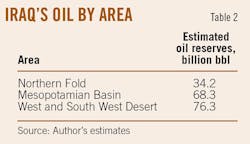

Iraq's oil reserves are estimated at about 110 billion bbl of oil, including 102 billion bbl of commercial reserves and 8 billion bbl of technical reserves that are not under development.

In October 2010, the Ministry of Oil published reserves data for 66 oil fields with combined reserves of 143 billion bbl. Discoveries in Kurdistan were excluded from the list.

The reserves of many of the fields had not changed from previous Iraqi figures. The largest increases were made at West Qurna, which jumped to 43 billion bbl from 21 billion and Zubair, which increased to 7.8 billion bbl from 4.1 billion.

By some Iraqi estimates, there is the potential for 350 billion bbl ultimately to be discovered in Iraq. This view is based on the fact that some 400 structural anomalies and leads have been mapped but never drilled, more than half of which are considered to have a high degree of certainty.

Reserves growth is expected in three major geographic provinces: the Mesopotamian sedimentary basin, Western Desert, and Kurdistan Region. From available geological and geophysical surveys, well tests, and petrophysical data using analog fields to correlate with similar structures, the author has made conservative recovery estimates for the three provinces (Table 2).

The author's estimates do not include any of this yet-to-find potential and therefore reflects a fairly conservative view.

Iraq has estimated gas reserves of 100-110 tcf of gas, around 70% of which is solution gas, primarily associated with the giant oil fields in the southeast of the country. Reserves of 15-20 tcf of nonassociated gas are in seven fields mainly in northern Iraq.

As with oil, the potential for growth in Iraq's gas reserves is very high given the limited extent of exploration. Furthermore, exploration has been focused on oil targets, which has meant that many gas discoveries have never been fully appraised. The discovery of Akkas gas field in Ordovician sandstone indicated the Western Desert as a potential gas province.

Iraq's overall yet-to-find gas potential has been estimated at 500 tcf, split 60/40 between nonassociated and associated reserves.

Petroleum systems

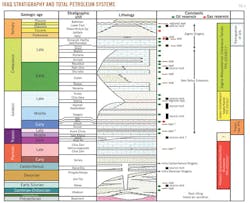

Oil reserves are found in two distinct basins in Iraq: the Zagros basin and the Arabian basin.

The Arabian basin is subdivided into several separate subbasins: the Zagros Mesopotamian basin, Widyan basin, Sinjar subbasin, and the Rutbah uplift.

Iraq has a limited coastline (i.e., without the claimed zone of at least 100 km from the existing border with Kuwait), and all of Iraq's oil fields are onshore.

The majority of fields and discoveries are in the Folded Zone and the Mesopotamian basin, which has the fields in northern, northeastern, and southern Iraq. The majority of Iraq's hydrocarbon reserves are in Cretaceous and Tertiary reservoirs. While potential remains in the underexplored Jurassic, Triassic, and Paleozoic systems, the unexplored areas offer a diverse range of opportunities.

The relatively unexplored blocks are:

• Block 1, in the Khleisia high and Sanjar trough. Two exploration wells were tested from Miocene and oil shows in Mesozoic.

• Block 2, one exploration well with oil stains in Cretaceous.

• Block 3, near Akkas field.

• Block 4, near Akkas and Risha field in Jordan.

• Block 5, near Akkas and Risha field.

• Block 6, no exploration wells, but a number of structures can be discovered.

• The latter three blocks could have potential in Paleozoic, Ordovician, and Jurassic targets.

• Block 11, in the Salman zone, one exploration well.

• Block 12, one exploration well, both blocks could be Cretaceous and Jurassic.

Block 8 is on the border between the Mesopotamian basin and the Folded Zone, and Block 9 is near one exploration well in the Mesopotamian basin. Blocks 8 and 9 lie within well-explored and recognized petroleum zones.

Block 7 is in the Mesopotamian basin, near one exploration well and close to existing appraised discoveries, with possible targets in Cretaceous.

Block 10 is on the border between the Mesopotamian basin and largely unexplored Salman Zone, where discoveries are possible in the Cretaceous.

The principal tectonic elements are shown together with the outline of the evaluated blocks on Fig. 1, and the stratigraphic nomenclature is shown in Fig. 2.

Seismic interpretation

Block 1: Five leads are identified in Block 1. They are in Upper Cretaceous Shiranish and a number of potential Cretaceous, Jurassic, and Triassic Kurra Chine and Ordovician Khabour levels.

Block 2: Six leads are recognized in Block 2 in the Kurra Chine and Khabour levels.

Block 3: This block has eight leads. These are defined by the Ga'ara and Khabour depth structure.

Blocks 4 and 5: Four leads have been identified. There is a significant area in the west of the block that has no seismic.

Block 7: This area is in central Iraq in the Mesopotamian basin. Overall the potential structures in Block 7 are relatively small, and 10 leads were identified.

Block 8: The block is in eastern Iraq close to the Iranian border. The block has no wells, but there are a number of wells associated with fields and discoveries surrounding the block. Mansuriyah-1 (1978), Jeria Pica-1 (1975), Nau Doman-1 (1978), Naft Khaneh-1 (1920), and Tel Ghazal-1 (1980) are all situated to the northeast of the northern part of the block targeting large anticlinal structures. Badrah-1 is east of the southern part of the block and was drilled in 1978 targeting a large anticlinal structure. Six leads have been identified at Upper Fars and Jeribe-Euphrates level. It is possible that the identified leads may increase in size and also that more leads may be identified throughout the block.

Block 9 is in southeastern Iraq adjacent to Iran in the Mesopotamian Zone and has no wells. Locations of five wells outside the block were available, although only formation tops for two wells (Nahr Umr-2 and Nahr Umr-3) were available. Nahr Umr field is 5 km west of Block 9, and Sindabad field is 1 km south of the block and is also intersected by seismic data. Zubair, Majnoon, and Siba fields are nearby and on trend with Block 9. Three leads have been identified. There is potential for a large number of reservoirs to be hydrocarbon bearing as the structure is expressed throughout the overlying horizons. Majnoon has as many as 12 oil-bearing reservoirs down to the Cretaceous level. Three leads have been identified at Upper Zubair level, which was oil-bearing in the Luhais-1 well.

Blocks 6, 11, and 12 are in southwestern Iraq. Data quality is fair. Safawi-1 is 15 km south of Block 6 but on a seismic line that extends into the block. Ghalaisan-1, in Block 11, was drilled in 1960 to 1,991 m as a stratigraphic test on a positive gravity anomaly. Nine leads were identified in Block 6 at three stratigraphic levels. Samawa-1 is 50 km east of Block 11 and was drilled in 1958 to 3,841 m to explore the Samawa prospect to Jurassic level. Ubaid-1 is 20 km south of Block 12 and was drilled in 1960. Shawiya-1 is in Block 12 and was drilled in 1960 to 1,784 m as an exploration well located on a positive gravity anomaly and on the southwest flank of a surface fold. Three leads have been identified at Upper Zubair level, which was oil bearing in the Luhais-1 well.

Petrophysical analysis

Most of the wells were drilled in the 1960s or 1970s and have primitive logs, commonly consisting of only an SP and a resistivity log.

The problem in many wells is the determination of a good porosity, water salinity, mud resistivity, and formation mud resistivity. Porosity determination is only possible in six exploration wells; water salinity was only available for three wells.

The absence of mud resistivity does eliminate determination of Rw. The water saturations determined are therefore estimates.

Main reservoir properties

The author has collected data from producing and nonproducing analog fields including formation volume factors and correlated them to the formations expected to be present in the fourth round blocks.

Available porosity and permeability data have also been summarized on the oil ministry's reservoir quality maps. Analog data for fields in Iran, Syria, and Saudi Arabia have been taken from published data. Information on potential reservoirs was taken from oil ministry reports on northern and western Iraq and from Aqrawi et al., 2010, and Jassim and Goff, 2006.

Akkas and Khabour formations

Akkas field is in northwestern Iraq near the Iraq-Syria border.

The Akkas-1 well produced wet and dry gas. The specific gravity in Akkas-1 was 0.726-0.6953 for the gas and 0.7792 for the condensate. There are also indications of light oil with a density of 0.8326 g/cu cm. Akkas-4 tested natural gas, but condensate is also believed to be present.

The Khabour formation is the oldest known sedimentary rock unit in Iraq. It consists entirely of siliciclastic sequences, comprising thin-bedded, fine-grained sandstone, quartzite graywackes, and silty micaceous shale with some intercalation of dolomite and limestone.

The base of the formation has not been reached in wells, and the Khabour may be more than 1,000 m thick. It was deposited in shallow marine inner to outer neritic environments that prevailed over the entire eastern part of the Arabian Plate.

Ga'ara formation

The Ga'ara can be divided into lower and upper units, similar to its time equivalents in Saudi Arabia, the Al-Khlata and Unayzah formations.

It is at least 120 m thick at Tlul Afyef and Wadi Duwaikhal and 450 m in the Kh-5/1 well. It is also present in shallow boreholes and trenches in the western desert. In West Kifl-1, a 50-m thick section of the Ga'ara formation consists of cross-bedded sandstones.

Kurra Chine formation

Triassic reservoir rocks in Iraq contain <1% of the country's proved reserves, although several fields in NW Iraq and NE Syria have produced significant volumes of oil and gas from Triassic reservoirs during production tests.

The most important reservoir rocks occur in the 500 m thick Upper Triassic Kurra Chine formation, for example in Butmah, Sufaiyah, and Alan oil fields in north Iraq and in the Kurra Chine and Butmah formations in Souedie, Rumelan, Jebissa, and Tishreen fields in Syria.

The main producing interval in Iraq lies in the carbonates of the upper part of the Kurra Chine formation, which occur between two thick anhydrite intervals.

Yamama formation

The Cretaceous Yamama formation contains hydrocarbons at 26 structures in southern Iraq including West Qurna, North Rumaila, and Majnoon fields.

The formation consists largely of shallow water carbonates. Reservoir limestones were deposited in oolitic shoals as low energy, shallow marine carbonates and ramp/slope facies in central Iraq.

The Yamama reservoir averages 240 m thick. Reservoir quality is best in central Iraq and is poor in eastern Iraq. Porosities average 6-12%, and permeabilities range from tens to hundreds of millidarcies. Porosity is dominated by intergranular macroporosity and some intragranular to chalky matrix microporosity, with local secondary porosity.

Zubair formation

The most important sandstone reservoir in southern Iraq is the Zubair formation with 30% of Iraq's hydrocarbon reserves.

The Zubair is recorded as oil bearing in 30 structures including Rumaila North and South and Zubair as well as East Baghdad in central Iraq. The Zubair forms a secondary reservoir at Ratawi, Tuba, and Luhais, and contains smaller reserves at Majnoon, Halfaya, and Huwaiza.

East Baghdad and Balad fields and the Mileh Tharthar-1 well lie just within the sandstone facies.

Sandstones of the Zubair formation were deposited in a delta/prodelta to inner shelf setting and consist of interbedded sandstone and shale 300-400 m thick. Net to gross in the Zubair formation is around zero near the Iran border; a thickness of over 200 m of sandstone is present in Zubair field and the Karbala area of central Iraq. Porosities likewise increase from an average of 15% near the border with Iran to around 30% in wells in Salman Zone such as Kifl-1.

Mishrif formation

The Mishrif is the most important carbonate reservoir in southeastern Iraq and contains oil at 32 structures.

The largest accumulations are in Rumaila North, Rumaila South, West Qurna, Zubair, Majnoon, and Halfaya fields, located on large-scale north-south trending anticlines.

At least 15 other commercial oil accumulations in the Mishrif formation have been discovered in southeastern Iraq; Abu Ghurab, Ahdab, Amara, Buzurgan, Dujaila, Jebel Fauqi, Gharaf, Huwaiza, Kumait, Nahr Umr, Noor, Rafidain, Rafidain E., Ratawi, and Tuba.

Gaddo (1971) reported mean porosities of 9% at Zubair and 16% at Rumaila. Porosities of up to 36% and permeabilities of up to 1,560 md occur in rudist-rich carbonates. Reservoir thicknesses of several hundred meters and a high net-to-gross (often >90%) are also recorded.

The Mishrif formation play occupies a relatively narrow belt running NW-SE across central and southeastern Iraq. Reservoir quality decreases toward the Najaf intrashelf basin to the southwest. The reservoir is massive in the center of the Mishrif maximum isopach in southeastern Iraq along the border with Iran.

Upper Fars formation

The formation is typically 600-800 m thick and is sometimes called the Injana formation along the main Baghdad-Kirkuk road in the northeast limb of Jebel Hamrin South.

A supplementary type section occurs in the Gilabat-1 well. The formation is 620 m thick.

Euphrates formation

The shelf carbonate that is equivalent to the Serikagni formation is the Euphrates limestone formation.

This formation reaches a maximum thickness of over 50 m at the Jambur structure, where it is thickest at the expense of the underlying Serikagni formation.

The Miocene Euphrates formation is the youngest unit in the first pay at Kirkuk. It produces oil at Bai Hassan, Jambur, and Naft Khanah, and it contains heavy oil at Qasaba, Jawan, Najmah, and Qaiyarah.

Reservoir quality improves toward the top of the formation. The formation may form a reservoir in more basin center locations than the Kirkuk Group, and may be important in Central Iraq, for example at East Baghdad, Balad, Samarra, and Tikrit.

Jeribe formation

The Miocene Jeribe limestone formation with maximum thickness of 63 m was recorded at the Injana-5 well.

The Jeribe produces oil at Jambur and Naft Khanah. It contains heavy oil at Qasab, Jawan, Najmah, and Qaiyarah and minor oil in the Euphrates graben. At East Baghdad, extensive sheet-like intervals of anhydrite are interbedded within the reservoir carbonate.

In common with the Jeribe formation, the Euphrates formation has reservoir potential in basin center locations such Tikrit, Balad, and Samarra. The main limestone produces oil at the Judaida, Khabbaz, Ajeel, and Hamrin fields in north-central Iraq and at Jebel Fauqi, Halfaya, and Buzurgan in southeast Iraq.

Mauddud/Qamchuqa

The formations are mostly dolomites and neritic, detritial-organic limestones and some undolomitized, detrital limestones.

The Qamchuqa formation to the north and northeast has producing reservoirs; they are vuggy, fractured, and sealed. In cenral Iraq, fair to good-quality sandstones and excellent quality organic limestones occur in a paleobasin centered around Baghdad. Probable primary porosity is 7-14% with secondary fracturing improving values.

In southeast Iraq, toward Basrah, carbonate reservoirs are slightly tectonically fractured and generally well sealed. The entire region west of the Tel Hajar-1 well in northern Iraq to the Safawi-1 well in the south has no preserved Mauddud formation.

Hartha formation

This Upper Campanian-Maastrichtian Hartha formation is about 200 m thick in southern Iraq, 350 m in the northern areas, but commonly much less on the summits of large structures than long flanks.

At the type locality Zubair-3 well (1,704-1,833 m), the formation comprises organic, detrital, glauconitic limestones, locally dolomitized, with grey marls and green shales. Chalky beds are common at Buzurgan, Ghalaisan, Dujaila, Kifl, Musaiyab, Siba, and Ubaid; oolitic layers are found at Luhais and Rachi, and marly or clayey limestones are more common in the Buzurgan area.

The Hartha has potential at Jawan, Majnoon, Falluja, East Baghdad, Najmah, Bai Hassan, and Tikrit. Oil has been tested at Nahr Umr, Alan, Atshan, Sammara, Kifl, Afaq, Samawa, Ghalaisan, Musaiyib, Makhul, Sassan, Ratawi, and Rachi.

Shiranish formation

The Upper Campanian-Maastrichtian Shiranish formation is directly above the Hartha and may even provide excellent regional seals to its reservoir.

Elsewhere, the basal part of the Shiranish is age-equivalent to the Hartha, and the top part is age- equivalent to the Tayarat formation. Light oil was produced from fractures in well-indurated, marly planktonic formaminiferal limestones of the Shiranish formation at Ain Zalah and Butmah fields.

Najmah formation

The Najmah formation is largely composed of oolitic limestone that is locally dolomitized.

Deposition was in a shallow marine or outer ramp/slope setting, with deep basinal carbonates also developed in the north. The thickness of the Najmah formation decreases northwards and eastwards. This is also reflected by reservoir quality, which is better in the south. Porosity of the Najmah formation averages 10%.

Nahr Umr formation

The Nahr Umr is a mixed carbonate/clastic unit consisting of coarse, shallow marine clastics together with shallow marine carbonates (outer ramp and slope) occupying more distal settings in eastern Iraq.

Sediment was sourced from the southwest. Deep basinal carbonates were deposited in the most distal parts in the northwest. Thickness of the Nahr Umr formation is greatest in the southeast (up to 360 m), but drops to zero in parts of northeast Iraq.

Reservoir potential is best in the shallow marine clastics and the shallow-water carbonates, particularly where they are dolomitized, but the reservoir risk is high in northern Iraq where the formation is thin or absent.

Recovery forecast

Recoverable resources have been estimated based on preliminary deterministic volumetric calculations (Table 3).

The P50 recoverable values have been generated using the recovery factor and oil in place volumes for each lead considered in the blocks. It has been assumed that all leads contain oil or gas.

Recoverable volumes are estimated at 12-16 million stb/well of oil and 60-120 bscf/well of gas.

Oil and gas plateau rates vary by field. Duration of plateau production is estimated at 3-8 years for oil and 3-15 years for gas in the various areas. These assumptions are based on the production histories of analog fields.

It is assumed that an oil well can be drilled and completed in 30 days and a gas well in 40 days.

Production forecast

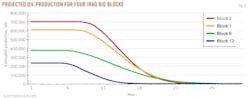

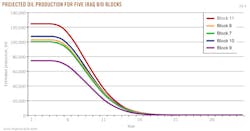

The author has estimated production forecasts for nine of the 12 fourth-round blocks based on a number of assumptions (Figs. 3 and 4).

The estimates are based on the known reservoir properties of nearby fields.

The selected main targets are:

• Kurra Chine formation which mainly consists predominantly of dolomites and forms the Upper Triassic reservoir in northwestern Iraq, where it extends into northeastern and central Syria as a main pay zone. Light oil has been produced from fractured Kurra Chine dolomites in Butmah and Alan fields at depths of 2,757-3,195 m. The gross thickness of the Kurra Chine reservoir in Butmah field varies from 85 m to 274 m. The reservoir has a relatively low to moderate porosity of 5-15%. Predominant pore types are fracture and intercrystalline. Reservoir quality of the Kurra Chine dolomite in Sufuya field, near blocks 1 and 2, is better than that of the Souedie field in Syria, with an average of 20% porosity and an average permeability of 40 md in Safaya field, but an average porosity of only 8% in Souedie.

• The Najmah formation surrounding blocks 6, 11, and 12 consists of peloidal-oolitic packstones and grainstones and forms the Upper Jurassic reservoirs for some fields in southern Iraq (e.g., Ratawi, Samawa, and Rumaila fields). Stratigraphically, it is the lateral equivalent of the Arab-D reservoir that forms the main pay zones in Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and western Abu Dhabi. The author used the reservoir properties of fields that are close to blocks 7 and 10.

Capital and operating expenditures

Several leads were identified in each block with differing hydrocarbon presumption classifications.

Generally, all the identified leads were estimated on a "stand-alone" basis whereby most of the resources would have their own committed gas oil separation plant.

It is assumed that the very large gas resources identified in blocks 1 and 2 would be partially used for Iraqi electricity power generation, petrochemical and private sector basic industry, as well export via Turkey or Syria to Europe or liquefaction at, for example, Ceyhan or Banias. The cost for the export pipelines to the mentioned ports is matter of agreement between the IOCs and the MoO. The author created a matrix of costs for the following:

• Geology and geophysics.

• General and administrative.

• Drilling (exploration/appraisal/development).

• Gas oil separation plant.

• Gathering systems.

• Export and tie-in.

• Infrastructure and camping.

• Security costs.

• Indirect costs.

• Contingencies.

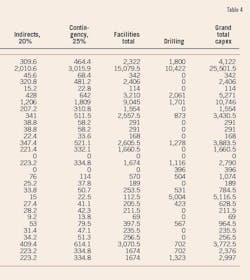

Drilling costs were estimated from the actual similar wells drilled in Iraq by international service companies. The average cost is $9 million for oil wells and $12 million for gas wells. The author didn't consider the cost of drilling oil wells by the state Iraqi Drilling Co., which is $5.5 million, or by Chinese drilling contracts that charge even less.

It is known that targets are identified at differing depths and well types may be more costly. Indirect costs were applied at a standard rate of 20% of the base facilities costs. Contingency allowance was similarly applied at a rate of 25% of the base and indirect costs (Table 4).

Opex boe was determined by estimating the potential life of field of each reservoir. The Opex was declined over the field life using factors and percentages to give an overall life of field (LOF) Opex cost.

Acknowledgment

This article is the author's personal work and is not related to his employment at RWE Dea.

Bibliography

Oil Ministry Report, 2001.

Iraq Oil Ministry Fourth Bid Round, 2010.

Aqrawi, A.A.M., Goff, J.C., Horbury, A.D., and Sadooni, F.N., "The petroleum geology of Iraq," Scientific Press, 2010, 424 pp.

Country Overview Iraq Middle East-NW Arabia Upstream Service, December 2010, p. 4 of 5 pp.

Jassim, Saad Z., and Goff, Jeremy C., "The Geology of Iraq," Dolin Publishing, 2006, 341 pp.

Al-Ameri, T.K., "Silurian palynostratigraphy and the unconformable boundary with the Devonian, western Iraqi desert," Iraqi Journal of Science, Vol. 41c, 2000, pp. 119-37.

Al-Ameri, T.K., and Baban, D.H.A., 2002, "Hydrocarbon generation potential of the Lower Palaeozoic succession, western Iraqi desert," Iraqi Journal of Science, Vol. 43, No. 3, 2002, pp. 77-119.

Abawi, T.S., "Foraminifera, stratigraphy and sedimentary environment of the Euphrates formation, Lower Miocene, Sinjar area, northwestern Iraq," Newsl. Stratigr., Vol. 21, Part 1, 1989, pp. 15-24.

Oil Exploration Co. Report, 2001.

Mazeel, M., "Siba Gas Field Development Plan: Subsurface Uncertainties and Economic Criteria," Middle East Economic Survey, Vol. 53, No. 27, 2010.

Aqrawi, A.A.M., Mahdi, T.A., Sherwani, G.H., and Horbury, A.D., "Characterisation of the Mid-Cretaceous Mishrif Reservoir of the Southern Mesopotamian Basin, Iraq," AAPG Search and Discovery Article 50264, 2010.

Mazeel, M., "Iraq's Technical Service Contracts—A Good Deal For Iraq?," Middle East Economic Survey, Vol. 53, No. 3, 2010.

Mazeel, M., "Iraq's Ahdab oil field development limits contractor profitability," OGJ, Aug. 1, 2011, p. 62.

Mazeel, M., "Hydrocarbon potential, reservoir development estimated for western Iraq's Akkas gas field," OGJ, Oct. 3, 2011, p. 86.

The author

More Oil & Gas Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com