Review suggests draft SPE PRMS 2017 unfit for public resource reporting

Bob Harrison

Patrick Quinn

Lloyd's Register

London

After 5 years of effort, the Society of Petroleum Engineer's (SPE) draft Petroleum Resource Management System (PRMS) 2017 constitutes a missed opportunity to eliminate subjectivity and lack of transparency in the guideline. Without more clarity and prescription, PRMS remains unfit for public reporting in the financial and governmental sectors. The SPE board should reject the proposed changes and address the problems outlined in this article to make PRMS a stronger tool.

Petroleum resource classification

The PRMS was published in 2007 to establish a universal language to classify petroleum resources based both on their commercial potential and uncertainty in estimates of their recoverable resources. The tool is applied to specific projects to estimate their chances of commerciality and expected recovery volumes. Designed to aid in-house management of exploration asset portfolios, PRMS has been adopted by several governments and stock exchanges for resource reporting and disclosure, which are roles that were never originally intended for it.

In February 2013, the SPE board agreed with the recommendation of its Oil and Gas Reserves Committee (OGRC) to proceed with an update to PRMS. After reviewing public comments on the draft, SPE plans to issue the new PRMS in 2018.1

PRMS is based on principles rather than rules. From a resource evaluator's perspective, its flexibility, subjective language, and loose definitions have made it too ambiguous for auditing. This article presents concerns regarding a review of the PRMS draft to gauge its fitness for the external reporting role it is being expected to fulfill.

Flexibility limitations

The increased use of subjective language in the draft-preferring recommending terms "may" to mandatory terms "must"-goes against PRMS goals of defining fundamental principles and providing a consistent approach to estimating petroleum quantities. The new definitions are even more flexible and ambiguous than the ones they replace and would lessen clarity and protection for oil and gas investors. PRMS application would be more difficult and would likely result in misalignment between regulators, companies, investors, and auditors. For example, the often misinterpreted and misused term "reasonable certainty" is a probability statement without an assigned probability and should have been replaced with "high degree of confidence."2

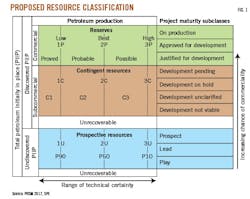

Fig. 1 shows the proposed changes to the PRMS resource classification framework with the addition of incremental deterministic cases for P1, P2, and P3 reserves and C1, C2, and C3 contingent resources as well as deterministic cases for 1U, 2U, and 3U prospective resources, where U stands for undiscovered.

These changes imply that the resource estimates from the scenario and incremental deterministic approaches and probabilistic methods are interchangeable. This misguided assumption of compatibility between the methods is further reinforced by the draft stating that any of the methods can be used and that the subsequent results should be reconcilable, which is nearly impossible to achieve.3

Contingent resources

PRMS 2017 also redraws the petroleum production box. There are now four contingent resource subclasses, and the chance-of-commerciality arrow stops at the interface between contingent resources and reserves. This implies that all classes of reserves have a 100% chance of commerciality, yet the text defines the justified-for-development subclass as a project that has yet to attain the necessary approvals and sales contracts for development. The draft also states that reserves should stay no longer than 5 years in this subclass, far longer than some regulators would permit.4

The system draft's distinction between commercial and economic remains unclear, and parties will continue to use the words interchangeably despite their different meanings. The draft introduces text that is contrary to the project-based principle of PRMS that reserves must be commercial within a company's capital cost, as opposed to economically producible at a 0% discount rate, which is the US Securities and Exchange Commission's (SEC) definition.

The flouting of the project principle becomes even more concerning as a result of new wording implying that, for reserves and contingent resources, the defined project development scenarios for the 1P-1C, 2P-2C, and 3P-3C cases do not have to be the same; well numbers and facilities can vary. This interpretation contradicts the PRMS tenet that reserves are project-based and require an approved technically mature development plan under which a well either meets the reserves' classification criteria and has a range of technical 1P, 2P, and 3P outcomes, or it does not meet the criteria and cannot be classified as reserves.

Similarly, for contingent resources, an area with less development certainty must be treated as a separate project with its own 1C, 2C, and 3C outcomes. Such an area must be assigned a lower chance of commercial development and must not be included in the existing project's 2C estimate and excluded from the 1C outcome. Varying the project scope is no better than using split conditions in the classification, which is not allowed in PRMS.

Consumption as reserves, decommissioning

PRMS defines reserves as net sales quantities measured at the reference point. The proposed draft states that fuel gas used within the project, which never reaches market and was previously identified as a separate nonsales quantity (honoring material balance), may now be included in reserves. Booking resources that are consumed in operations is unwarranted and should be removed from the 2017 draft entirely.

Savings from on site fuel usage are already incorporated in the project's economic model as lower operational expenditure, which is used to calculate the economic limit and define reserves. Hence, booking fuel gas as reserves is double counting and would lead to a fictitious increase in quoted reserves. This methodology also would require mature fields relying on external fuel sources for continued operations to be booked with negative gas reserves, further exposing the lack of equality in counting reserves.

The treatment of decommissioning remains unclear in the draft.5 Lloyd's Register solicited an official response from the OGRC and discovered that PRMS implicitly assumes that sufficient funds have been set aside for the abandonment of developed projects. This assumption is not mentioned in the guidelines.

References

1. Society of Petroleum Engineers (SPE), "Draft PRMS for Comment," PRMS (2017), www.spe.org.

2. Harrison, B. and Falcone, G., "Are we reasonably certain that reasonable certainty adequately defines uncertainty in our reserves estimates?" SPE No. 185496, SPE Latin America and Caribbean Petroleum Engineering Conference, May 17-19, 2017, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

3. Cronquist, C. (1991) "Reserves and probabilities: Synergism or Anachronism?" Journal of Petroleum Technology, Vol. 43, No. 10, October 1991.

4. Kreft, E., Scheffers, B.C., Godderij, R., "The value added of five years SPE-PRMS," SPE No. 170885, SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Oct. 27-29, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

5. Harrison, B. and Falcone, G., "Handling decommissioning and restoration liabilities within PRMS and their impact on reported reserves of producing fields approaching abandonment," SPE No. 185497, SPE Latin America and Caribbean Petroleum Engineering Conference, May 17-19, 2017, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

The authors

Bob Harrison ([email protected]) is project director and subsurface technical authority with Lloyd's Register. Before this, he worked for British Gas and Enterprise Oil, and then as a freelance consultant. He gained an MS (1982) in petroleum engineering at Imperial College, London. He is a certified Competent Person, past chairman of the Society of Petroleum Evaluation Engineers (SPEE) Europe Chapter, former member of the SPE OGRC, and a fellow of the Energy Institute.

Patrick Quinn ([email protected]) is principal reservoir engineer and project manager in the Lloyd's Register reserves and asset evaluation team. Before this he held positions with British Petroleum and Total SA. He gained a BS (1979) in petroleum engineering at Imperial College, London. He is a certified Competent Person and a member of the SPEE Europe Chapter.