South Texas county addresses disposal concerns

Tayvis Dunnahoe, Editor

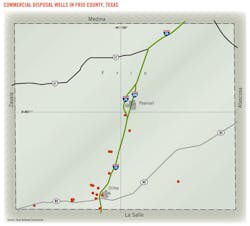

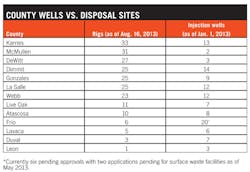

FRIO COUNTY, Tex.—Drilling for oil and gas has been limited in Frio County, yet it has the largest population of wells for wastewater disposal, or wastewater injection, in South Texas.

With 10 active commercial disposal wells, 10 more approved, and six awaiting permit application review, county officials are working to determine the draw for this secondary activity.

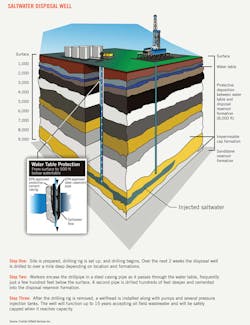

Part of the answer is geological. The county resides directly above the Olmos formation. This oil- and mostly water-bearing formation provides a 1,000-ft thick depository for disposal wastewater. At a depth range of 4,500-5,500 ft, the Olmos is firmly capped by a 1,600-ft layer of shale. The concern for residents is the Carrizo aquifer, which lies at a depth of 1,200-1,900 ft.

Technologically, injection wells are environmentally sound, and the practice of disposing of produced water is common in many states throughout the US. The process also is relatively inexpensive, and when applied properly it can be fairly nonintrusive to local communities.

In Frio County's case, the sheer abundance of new disposal sites has raised local concern.

While environmental risks such as contaminating ground and surface water are a major source of concern, the county also is working on increased truck traffic, road repair, ensuring public safety, and increasing preparedness for emergency response.

Water management lifecycle

The Eagle Ford shale is a frontrunner for economic stimulus and increased production among similar North American plays. Since 2008, companies have used the latest advances in technology to identify the central core of this vast resource play, which has resulted in many success stories for early adopters.

Aside from increased production, decreased drilling times, and returns on investment, certain processes such as wastewater disposal come primarily as an operating expense. On the front end, water management involves many advanced technologies including reuse and recycling.

In areas like Pennsylvania's Marcellus, injection wells are not permitted because of the lack of proper geology in the region. Recycling and water reuse have increased substantially in the Marcellus region. The state of Ohio has some injection well capacity. When feasible, companies transport produced water to these sites. From a cost perspective, disposing of water through injection remains the least expensive option. Recycling is encouraged, and many operators use the process to alleviate pressures garnered from accessing fresh water. Recent technologies such as waterless fracing, which uses liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), may soon alleviate pressure on water resources and decrease net disposal rates, but the technology is still fairly new.

In South Texas, the process of wastewater injection is the preferred method of disposal. It is important to note shale development does not account for 100% of the water currently injected. There are many sources for produced water including stripper wells throughout the state that produce moslty water with limited amounts of saleable oil. Flowback water from the region's shale development supplies a large portion of disposed water in Frio County, but injection totals comprise volumes from many sources.

Access and location can affect the bottom line for many operators. In the Marcellus example, transporting water into Ohio for disposal can be cost prohibitive, hence the increase in reuse technology. For Frio County, Interstate 35 (I-35) offers an easily accessible route for most Eagle Ford operations. As a result, both Pearsall and Dilley, Tex., have been inundated with associated traffic from wastewater disposal.

Increased production

According to the Texas Railroad Commission (RRC), the Eagle Ford's production reached nearly 600,000 b/d in June. In 2008, production averaged 352 b/d from the Eagle Ford shale. This increase has brought major changes to South Texas within the last 5 years.

In 2010, Frio County contained seven disposal wells that took on 620,000 bbl of produced water. By yearend 2012, the county had 10 active disposal wells that received more than 10 million bbl of water. According to RRC data, this represented a 473% increase in the county's disposal intake. Frio County is projecting that 60.8 million bbl of wastewater will be disposed of by yearend.

The county is close to Karnes County, the most productive in the region with 46 million bbl of oil produced last year. La Salle and Dimmit counties, also near Frio, produced more than 44 million bbl of oil cumulatively last year. Frio County, which has experienced very little production, has become a unique feature in the overall picture of the Eagle Ford boom.

"If you look at the other counties, drilling activity is much higher than in Frio County, but the numbers for disposal wells lag by half," said Richard Graf, Frio County commissioner, Pct. 2. According to Sally Velasquez, a consultant who works on Frio County's behalf, the county receives more than 53% of the total wastewater coming from Eagle Ford production. As of Aug. 16, 2013, Frio County had eight active drilling rigs working within its border.

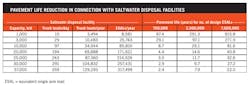

From a load-bearing standpoint, Frio County has had difficulty making its case that providing disposal well capacity comes with a cost that is, in some cases, greater than its neighboring counties that account for larger shares of Eagle Ford production.

The county recently worked with the 83rd Texas Legislature and its state leadership in Austin to add its disposal capacity to Senate Bill 1747, which was designed to assist energy development counties with roadway funding related to increased oil and gas activity. "We simply asked that the bill include language to account for disposal wells but were told that there was no formula related to disposal activity to justify adding it to the bill," Velasquez said. The Frio County officials then coordinated with the Texas Department of Transportation to develop data that could justify its role as an energy development county. Frio was eventually added to the bill.

The county is in a unique position. Many lawmakers as well as industry proponents base "energy development" involvement solely on drilling and production activity, which is marked by rig counts, completions, and production numbers. Because Frio County has very limited activity for these types of operations, it has been overlooked as providing a vital service to the recent boom. "In many cases, Frio County has more truck traffic than most high-production counties," Velasquez said. "A single disposal facility in Frio County can take on as many as 130 trucks/day on average. With an average load of 130 bbl of water, one facility can take on 16,900 b/d of wastewater. Monthly and yearly averages for a single disposal well are estimated at 50,700 bbl and 608,400 bbl, respectively."

Given its potential for 25 operational disposal wells by the end of the year, Frio County is actively pursuing recognition as a "producing county" based on the major increase in traffic from this process. For perspective, the county could see more than 350,000 truckloads on its roadways with 10 operational disposal wells in a single year. A producing county with 30 rigs actively drilling will see around 76,000 truckloads based on a 5-year average. Essentially, this accounts for nearly a fivefold increase in activity.

Using this formula, Frio County was successful in having injection wells added to the wording for Senate Bill 1747, which will provide matching grant funds to energy development counties for use in repairing roadways and other municipal programs related to increased oil and gas activity. While the grant will match 50% for producing counties, just 10% will be allocated in matching funds for counties primarily dealing with disposal well activity.

Environmental risks

As recently as 2009, RRC has denied applications for disposal wells because of a combination of resident concerns and a lack of data for the proposed injection well (see Oil and Gas Docket No. 01-0262406, RRC).

The environmental risks associated with disposal wells are manageable under the current standards provided by RRC.

According to US Geological Survey Chief Hydrologist George Ozona, "Some areas have seen recent concerns related to groundwater contamination, such as signs of arsenic in the Barnett and methane and carbon dioxide in the Marcellus, but no contamination has been detected in South Texas related to Eagle Ford shale development." Since 2010, USGS also has worked with the San Antonio River Authority. "Water samples have shown no constituents from unconventional development," Ozona said. The study is now focusing on the tributaries to further eliminate possible sources of contamination.

Permitting disposal wells in South Texas is not impossible, but the well must meet specific standards prior to being approved. In some cases a nonproductive well may be used, which is where Frio County officials are most concerned. Casing integrity is the key element, and applications must prove that the wellbore is properly isolated from the aquifer to prevent contamination. Neighboring wells also must be shown to be properly shut in to prevent communication with the aquifer as formation pressure changes with injection.

In other cases, a new well may be drilled. This process ensures proper isolation from local aquifers and provides a proper casing structure for the life of the disposal well. To date, RRC is actively restructuring its rules for disposal wells, and this process may see regulatory changes within the next several years.

On the surface, increased traffic provides a substantial risk for Frio County. Groundwater could be affected in the event of a collision. Malfunction at a disposal site also could lead to contamination of surface water. In addition to water contamination, other emergencies such as explosions, fires, and air quality issues are viewed with caution.

"The eye opener for us was an explosion and ensuing fire that caught us off guard in Pearsall," said Frio County Judge Carlos Garcia. In January 2012, a disposal well outside of Pearsall exploded when workers were welding near a storage tank. Located about 50 miles southwest of San Antonio, the town's volunteer fire department responded to the fire, which continued to burn for more than an hour. Three people were injured. With assistance from three nearby fire departments, the fire was extinguished with water and foam, requiring the efforts of 12 trucks and 33 firefighters.

"The lack of training for our emergency personnel put them at risk because the county had no experience fighting this type of fire," Garcia said, "and we were not equipped as first responders for this type of emergency." It was later discovered that the disposal well was privately owned and operated. RRC completed an initial investigation and determined that several ignition sources were close to gas-containing water. "This is one of the reasons we are working to raise awareness for these issue. We owe it to our constituents," Garcia said.

Finding middle ground

Water disposal is an operational expense. While virtually no revenue is attached to waste from oil and gas development from an operator's perspective, there is an essential cost for counties where this water is disposed. Private ownership of disposal wells can be problematic in the event of a catastrophe, yet the process is purely manageable if proper safety guidelines are followed. Both from a personal and environmental safety standpoint, water injection wells can be managed responsibly.

Meanwhile, the county must contend with the underlying issue of educating itself on the topic of wastewater disposal. "Waste is a curse word in any business," Graf said. "All waste is not necessarily toxic, but it's waste and, as such, it can contaminate." The goal for Frio County is to find oil and gas companies that are willing to talk about the issue. "It is better to prevent something from happening than to try and repair a major problem after it has already occurred," Graf said. "As leaders of the community, we have to be responsible. We have to say that we have done everything in our power to provide remediation if a major catastrophe were to take place."

Business generally aims to maximizing profit. In Frio County's case, its ability to maximize profit is hindered as counties in Texas typically have no statutory power or zoning authority to generate revenues with increased activity. For the disposal well market, landowners are in control of the process. But in general, the Eagle Ford boom has provided the county with similar benefits as its neighboring, producing counties. Retail surpluses, hotel and RV park rentals, and local job opportunities have grown.

"We've got nothing against the industry, but there are some negative sides to this issue that need to be addressed," Garcia explained. Risks associated to exponential growth of wastewater disposal capacity have placed undue pressures on the county's budget. Training first responders to fight chemical fires, keeping the roadways safe and in good repair, and putting aside funding to provide effective remediation in the event of a major catastrophe are issues that the county commissioners are actively pursuing. "Funding a major crisis would be difficult at this point. The county doesn't have the resources to deal with a major problem should something happen, and the state and federal governments say they don't have the resources either," Graf said. "So, who's going to help us to resolve an emergency situation?"

Frio County has proposed a county-based service fee on water disposal at a rate of 1¢/bbl to meet it budgetary concerns. This move has not garnered the county much assistance from the industry as impact fees are often bad for business.

"There is an extensive amount of disposal going on in this county," Graf said. "Whether we have drilling rigs or not, we have just as much traffic as any of the other counties from disposal." The goal, as stated by Frio County officials, is not to penalize its entrepeneurs. "As a commissioner we have to take note of the economic benefits of increased oil and gas activity, but we also must pay close attention to the environmental quality of our surroundings," Graf said.

Collaborative expansion

The Eagle Ford shale is anticipated to be productive through the next 20 to 25 years. "The water produced from here has to go somewhere—there is no question about that. But how much of this waste is going to be pumped into Frio County?" Graf asked. There are other counties that also have a good number of disposal wells.

As the Eagle Ford play continues to expand, more drilling and production activity will most likely enter Frio County, which could compound its problems should the trend of adding new disposal wells continue.

Frio County wants better monitoring for its disposal activity. Knowing what is being pumped, and at what pressures, could alleviate some of the concerns the commissioners currently have. "Some energy companies have volunteered to help with certain things," Graf said. "It takes the counties, cities, the local entrepreneurs, and the industry itself to deal with problems that we can't fix on our own," he said. "We have to find the best method to deal with these issues without becoming adversarial."