Study urges early Iraqi welcome of foreign investment

Iraq can accelerate reconstruction and boost its economic growth if it promptly welcomes foreign direct investment (FDI) to its oil industry and establishes a stable fiscal regime.

The fiscal format most appropriate to such a regime, says a study by the International Tax & Investment Center (ITIC), Washington, DC, is the production-sharing agreement (PSA).

Guidance on PSAs can come from other countries' experiences, the study points out. Although Iraq's political fragility means risk for investors, "international experience shows that political uncertainties need not deter core investments from getting under way."

Specialists from the Centre for Global Energy Studies, Oxford Economic Forecasting, and Transborder contributed to the study.

Need for capital

Having reestablished the ability to produce 2.5 million b/d of oil, Iraq needs to invest nearly $4 billion to raise capacity to the 1990 level of 3.5 million b/d. And pushing capacity to 5 million b/d requires investment of at least $25 billion during 2004-10.

Two thirds of that requirement would be for rehabilitation and development of oil fields and the rest for maintenance, logistics, and downstream operations. According to the ITIC study, 30-40% of the upstream funding could come from investors outside the country.

"This level of FDI enables Iraqi oil production to be at least 1.5 million b/d higher by 2010 than would otherwise transpire," the study says.

The study apportions potential spending like this: exploration, 3%; maintenance of production capacity and expansion of logistics, partly funded by FDI, 15%; new field and reservoir development, 17% funded by Iraq and 36% funded by FDI; damage repair and increase of production capacity to 3.5 million b/d, 15%; and refining, petrochemicals, and natural gas, 14%.

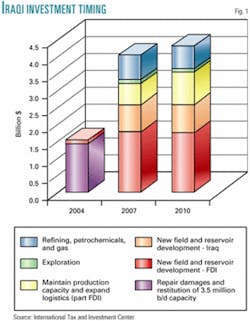

The producing sector of Iraq's oil and gas industry needs investments of $3.4 billion/year. The downstream segment's investments will vary between $100 million/year and $1 billion/year. Fig 1. shows when the investments might occur.

If Iraq doesn't welcome FDI, it will have to finance expansion of the oil production on which future economic growth depends with debt and oil revenues needed elsewhere.

Debt already is high. Depending on how much forgiveness creditors grant, Iraq owes foreign lenders $79-128 billion. If the eventual total is $90 billion, debt service would be $1 billion/year at first, rising to $2 billion/year by 2010.

The burden makes Iraqi finances vulnerable to low oil production and low oil prices and makes financing oil investments with debt difficult.

The FDI advantage

In addition to the higher oil production it could make possible, FDI thus would free Iraqi oil revenues for other essential uses.

But the production gain alone would be important: The ITIC study says every $1 gain in oil revenues can provide the basis for an extra $2 in GDP.

For example, ITIC says, raising Iraqi oil production to 5 million b/d from 3.5 million b/d with partial FDI financing would boost overall GDP by $14-45 billion 5 years after the initiation of FDI, depending on the oil price. The study says that if production doesn't expand and oil exports settle at 2-2.5 million b/d, GDP might reach $45-50 billion/year with the oil price at $25-30/bbl.

Financing oil expansion with FDI rather than from the Iraqi government's own resources would raise GDP by an additional $1.6 billion in the first year of FDI financing and a cumulative $8.5 billion by the fifth year, according to ITIC modeling based on an oil price of $25/bbl.

The government-revenue advantage of FDI-financed expansion would be $1.4 billion in the first year and $4.2 billion in the fifth year. The employment boost from FDI would be 100,000-150,000 jobs in the first year and 150,000-200,000 jobs in the fifth year (Fig. 2).

Investment conditions

If the government decides to allow FDI, the study says, it will have to clarify constitutional issues and adopt a format attractive to international investors.

The interim government lacks legislative power, and agreement on the new constitution "is unlikely to result in a quick resolution of the constitutional issues that must be settled before Iraq can establish a viable regime for foreign investment in the petroleum sector," the study says. It points out that the status of agreements between the previous regime and foreign companies remains unclear.

But the constitution gives the government title to oil and gas through a provision that should allow the establishment of a fiscal regime for foreign participation without private ownership of resources, the study argues.

If Iraq accommodates no foreign or nongovernment equity participation in current production, rehabilitation will have to be funded by government revenues with foreign participation handled by contracts.

Other possible options for Iraq include partial or full privatization of producing fields. An immediate problem with partial privatization would be ensuring the validity, after the interim government ends, of agreements made now. Full privatization by a future Iraqi government would raise challenges of asset valuation and the potential for scandal.

More likely are formats for agreements with foreign investments such as those Iraq used or discussed before 2003: PSAs, development and production contracts, and risk service contracts. The study considers PSAs preferable to the others.

"PSAs would result in an attractive investment environment, protect the interests of the state, but at the same time function more robustly in the face of changed circumstances and permit optimal recovery of petroleum from all fields," it says.

And it says that an Iraqi financial scheme, like those everywhere, should balance two sets of considerations.

"On the one hand, the package should minimize the additional risk (beyond pretax risk) to the investor of absolute loss; i.e., the tax should be profit-related.

"On the other hand, the package needs to offer the prospect of stability of contract terms." That means it should ensure the government won't change the contract to the investor's disadvantage if a project becomes especially profitable, the study says.

"It will do this only if it offers the prospect of a revenue yield that is perceived by government and the public as reasonable in the context of overall fiscal conditions and policy."