India eyes coalbed methane to supplement gas supply, but much more study needed

India's developing economy implies a spur in demand for new sources of energy, and coalbed methane is being pursued to supplement the gas supply and partially cover demand.

New projections indicate a huge coal resource on the order of 636 billion tonnes in Gondwana and Tertiary age. The majority of the Gondwana coal resource lies at shallow (mineable) depths, and the resource that may be available for CBM exploration lies predominantly in the 'inferred' and 'indicated' categories.

The production profile of Gondwana coals is typical of any CBM well. The coal reservoir, however, is heterogeneous due to its banded nature and lithotype, while the permeabilities encountered so far are low. The coal also seems to be "dry," resulting in early breakthrough of gas.

More exploratory inputs are required to evaluate the CBM potential of Indian lignites, which occur mainly in Tertiary basins.

Marketability of CBM in the states of Jharkhand and West Bengal may not pose problems, while in the state of Gujarat it will supplement the high demand for natural gas.

Introduction

Ever since announcement of India's new economic policy in 1991, the country has made rapid strides in development. This has led to increased demand for energy, creating a large gap due to limited supply.

To mitigate the burgeoning demand-supply gap, various indigenous and imported sources of energy are being considered to ensure the country's energy security and further economic development. Exploration is under way for CBM.

The scanty data available suggest Indian coals, like their Australian counterparts, to be low permeability, layered, and thus heterogeneous reservoirs. Such coals would require effective stimulation techniques and closer well spacing for achieving optimum production.

There is also a need to locate the 'fairways' for CBM as exploration proceeds. This article attempts to bring out the likely challenges that lie ahead in exploitation of the oft-quoted CBM resource of 1 tcm from coal and lignite and its marketability.

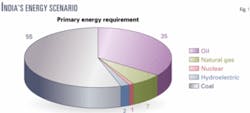

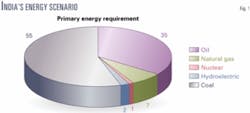

Coal is predominant among the multiple sources that feed India's energy requirement (Fig. 1). Natural gas production is on the order of 78 MMscmd, while its demand is 110 MMscmd, expected to grow to 230 MMscmd in 2006-07 and 390 MMscmd in 2025 (Fig. 2).1 This would require that other sources such as CBM and gas hydrates bridge the increase in gas demand.

Since CBM has matured from the R&D phase to the exploratory phase, it is now considered to be a strong option to supplement gas demand.

India embarked on evaluating its coal bearing sedimentary basins for CBM potential in the early 1990s.2 India's largest integrated petroleum concern, Oil & Natural Gas Corp., is the frontrunner in this activity. ONGC put India on the world CBM map in September 1997 when it successfully tested methane from a well in Jharia coal field.

The government of India has announced lucrative terms and conditions to attract investment in CBM exploration and production.3 4

A few contemporary private operators like Great Eastern Energy Corp., Reliance Industries Ltd., and Essar Oil Ltd., have indulged in some activities for CBM evaluation in Raniganj and Sohagpur coal fields and the Cambay basin, respectively.

India's coal resource

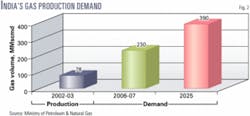

India has 240 billion tonnes (BT) of coal reserves, predominantly of Gondwana origin (Fig. 3).

In addition to these, 141+ BT are quoted as prognosticated resources.5 Several workers6 7 have also estimated lignite resources in the deeper Tertiary basins to be of the order of 254 BT. Total coal and lignite resources of the country may therefore be to the tune of 636 BT.

Coals in the Gondwana grabens with suitable rank have indicated CBM prospectivity. Gondwana grabens occur in aborted rift grabens along the Rajmahal-Damodar, Son-Mahanadi, Wardha-Godavari, and Satpura-Narmada river valleys from Satpura in the west to Raniganj in the east. Some of these Gondwana grabens like Jharia, East Bokaro, Raniganj, Karanpura, and Sohagpur are known for quality coals in the country.

A substantial amount of surface and shallow depth coal characteristic data is available for the coal fields that occur in the Gondwana grabens (Fig. 4), while data in the Tertiary basins are usually lacking on account of greater depths of occurrence and lack of exploration for methane in the lignites.

On the bases of rank, physico-chemical characteristics, prospective area available, depth of occurrence of coal seams, geological age, and present level of knowledge, the coal fields of India have been segregated into four categories (Table 1).8

Category I coal fields such as Jharia, Bokaro, North Karanpura, and Raniganj with huge coal thickness, high rank, and maturity compare well with global CBM producing coal fields in terms of gas content and adsorptive capacity.9

Category II and III coal fields predominantly occur in the Damodar and Mahanadi valleys (Fig. 3 and Table 2) but have a progressively lower rank of coal. The present level of knowledge is inadequate to upgrade these coal fields into a higher category.

Tertiary coal occurrences in India are known from the Cambay basin, Bikaner-Nagaur, and Barmer basins, Assam-Arakan basin, foothills of Jammu and Kashmir, and Neyvelli in the Cauvery basin. For the purpose of CBM exploration these have been placed in Category IV, as their CBM prospects are largely unknown.

It is unequivocally believed that large resources of coal are a prerequisite for a viable CBM venture. The following presents a critical review of the Indian coal resources that lie in Gondwana coal fields and their relevance from the CBM standpoint:

Total coal resource to a depth of 1,200 m: 240 BT.

Total coal resource to a depth of 600 m: 27%.

Total inferred and indicated resource: 73%.

It is thus evident that a majority of the proven coal resource lies at mineable depths, and since India is not presently practicing coal mine methane (CMM) and abandoned mine methane (AMM) activities, the coal actually available for virgin coalbed methane (VCBM) projects lies in the inferred and indicated categories.

Therefore, it becomes imperative for CBM operators to first prove the existence of coal in this category (inferred and indicated) before carrying out a full-fledged CBM project. Ample scope exists for exploring and proving/upgrading the lower categories of coal and lignites in the future in the interest of CBM exploration.

Quantifying the potential

Once the concept of CBM came to India, several agencies and researchers10-12 have attempted to 'quantify' their CBM potential.

Such figures vary from 0.8 tcm to 8 tcm for the coals of India, and this wide variation is attributed to paucity of specific CBM data and almost lack of coal exploration in the deeper plays. However, most of the workers tend to believe 1 tcm of CBM resource to be a realistic figure.

Optimistically about 50% of the same is considered recoverable, hence the CBM reserves could be considered to be of the order of 0.5 tcm as compared to conventional natural gas reserves of 0.76 tcm. Therefore it is felt that the CBM reserves could play a bridging role to supplement gas demand.

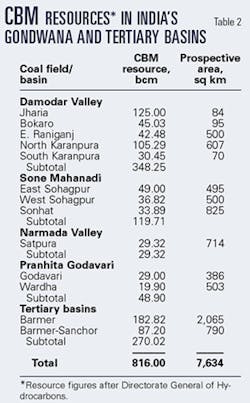

With the government's announcements of bidding rounds CBM I in 2001 and CBM II in 2003, a quick estimate of the country's CBM resource can be made, as both these offers have encompassed major parts of the areas that may be available for CBM exploration. The Damodar Valley is understandably the most preferred sector comprising the country's best quality coals, while the Barmer-Sanchor sector has gained importance on account of large acreage available (Table 2).

The total CBM resource offered in the above bidding rounds is 0.8 tcm. A quick estimate of other important coal fields like Talcher, Ib River, and Rajmahal Group indicates that another 0.2 tcm of CBM resource may also be available. The total CBM resource thus available in the market is of the order of 1 tcm and the acreage 7,600 sq km (Table 2 and Fig. 5).

India's CBM experience

Although theoretically CBM potential evaluation in India began in the early 1990s, it was Essar Oil Ltd. that drilled the first three wells for evaluating the CBM potential of Cambay basin.13

This was followed by ONGC drilling two wells in the Durgapur depression of the Raniganj coal field. Success eluded ONGC until it drilled the first well in the Jharia coal field, which tested CBM in 1997.

ONGC's modest beginning and perseverance in the field of CBM exploration has led to the understanding that for converting the above resources to reserves and putting them on production, several geological and technological challenges confront the domestic CBM industry.

In the case of Gondwana coals, their heterogeneity, thick multiple coal seams encountered in a long stratigraphic column, combined with hard and abrasive interseam partings could cause drilling and completion problems. Since Gondwana coal fields exhibit complex geology because of intricate fault systems, this could lead to small-scale compartmentalization and correlation and well spacing problems.

Chemical characteristics, especially high ash and moisture contents, could adversely affect the coals' storage capacity as these coals are allochthonous, while excess igneous activity has devolatized large areas of Gondwana coals which could result in poor CBM yields. It is also observed that nearly half of the total area and CBM resources available for CBM exploration fall in low category coal fields that would need necessary exploratory inputs prior to any CBM activity (Table 1).

Large quantum of lignite occurs in Indian Tertiary sedimentary basins (Fig. 3), the largest being in the Cambay basin. Very limited subsurface information on these lignites, specific to their methane potential, is available. The coal beds are intricately associated with hydrocarbon bearing horizons in the Sobhasan and Kalol area of the North Cambay basin.

From coal core studies it has been observed that cleats are uncommon in the lignito-bituminous seams. Incipient cleat development is noticed in a few bands, which have vitreous luster. These cleats are developed in orthogonal sets, are 1/2 cm to 1 cm apart, and are restricted to bands not exceeding 1 cm in thickness. The lack of cleats could possibly be compensated by fractures, which could develop near faults.

The coal normally occurs at a depth of more than 1,200 m. On the basis of sparse physiochemical data of the lignito-bituminous coal, Rao13 estimated the gas content to be 2-6 cu m/ton and the total CBM resource of about 0.2 tcm.

In view of the above, and also in view of the fact that this energy source would substantiate/replace the existing feedstock to different industries in Jharkhand and West Bengal states and complement the supply of gas in Gujarat, we discuss three critical parameters, i.e., permeability of Indian coals, production behavior of CBM wells, and marketability of the gas.

Permeability in Indian coals

Permeability is a critical factor in the extraction of methane from coal seams. It is a combination of micro porosity14 of the coal and the porosity generated by factures or cleats.

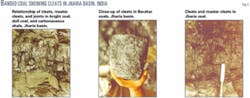

Megascopic examination of the coal from Damodar valley grabens shows banded coal (Fig. 6) with thin to thick laminae of vitrain. Lithotype is commonly clarain to dull clarain with development of open unmineralized cleat systems in vitrain bands. In consonance with their age, cleats have developed on two scales, i.e., with cleat frequencies of 3-4 cleats/cm (wide spacing) and 6-7 cleats/cm (close spacing).

There appears to be good development of cleat porosity in Category I coal fields (at least on megascopic scale). However, in Category III and IV basins such cleatings are not observed. Total core porosity in Middle Barakar coal and Lower Barakar coals in drilled wells in Jharia vary from 5.82% to 11.30% and 4.74% to 6.94%, respectively. A fairly high value (1.43% to 4.15%) of matrix porosity has been encountered in Jharia coal.

Air permeability is in the range of 0.23 md to 2.88 md and 0.03 md to 0.78 md for Middle and Lower Barakar seams, respectively.15 India's Gondwana coals, being layered reservoirs, have recorded low permeability like their Australian counterparts.

Even though the data are quite sparse, the younger Tertiary coals of the Cambay basin have also recorded low permeability in the range of 1-2.5 md at 1,350 m.7 It is thus imperative to identify fairways in Indian coal coal fields before the substantial resource locked up in them can be extracted.

Production behavior

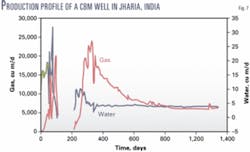

Only a few wells have been tested and have produced CBM successfully in the Jharia coal field, and their production behavior is discussed here.

Five objects were tested from the Barakar formation in a depth range of 545-806 m. The production profile over a period of three years is given in Fig. 7. This profile is akin to a typical CBM well where initially the rate of water production is high with low gas production. With time the gas production increases and water production declines, and stabilized flow rates are 5,000-6,000 cu m/day and 3-4 cu m/day, respectively.

The initial contribution of gas during commingled production of five objects was very high, and finally the production achieved stabilization when the gas flow was reduced to one-fifth (Fig. 7). This could reflect the impact of hydrofracturing in the initial stages of production when connectivity within the reservoir around the wellbore was adequate.

The increased production in the initial stages could also be attributed to production of free gas within the cleats/fractures in the coal seams. The subsequent lower gas production is attributed to poor connectivity farther from the well bore on account of moderate to poor matrix permeability. The remedy for such low permeability coal reservoirs lies in effective stimulation techniques for achieving greater "half-fracture length" and closer well spacing.

A similar production profile exists for the first CBM well in the Jharia coal field16 corroborating the above.

From this it appears that the Gondwana coals are relatively "dry" when compared to global examples. In this case, gas breakthrough takes place within a few days, while in the US there are examples of dewatering continuing for several months before the gas "breaks in."

In the case of the Tertiary coals/lignites of the Cambay basin, production testing was inconclusive because of large volumes of water and coal fines during testing.13

Marketing coalbed methane

With CBM activities gaining momentum in the Damodar Valley coal fields in Jharkhand and West Bengal states and in the Barmer-Sanchor basin in the north Cambay basin Rajasthan and Gujarat states, CBM may partly replace the conventional fossil fuel like coal in the former while it would augment the existing gas supply in the latter.

In Jharkhand and West Bengal, industries hard pressed for their energy requirements would respond enthusiastically to the idea of energy replacement, especially to an environmentally friendly source like CBM. The major industries are steel, power, and refractories.

Preliminary market survey indicates that all the above sectors are keen on this energy replacement if CBM is made available in the quantum required and at a comparable price. A gas demand of 5 MMscmd has been estimated for the industry and domestic sectors alone in Jharkhand, while in West Bengal both these sectors would require about 6 MMscmd.

The Gujarat government has an ambitious plan for accelerating the state's industrial growth. Gas demand is expected to reach 44 MMscmd by 2007 from the current level of 27 MMscmd. Presently about 9 MMscmd of gas is produced in Gujarat, and this figure is expected to increase to about 28 MMscmd by 2007.17

The CBM campaign would infuse new life and usher in an era of enhanced industrialization in this part of the country. Thus, it is evident that there is a vast market for CBM with its favorable economics and ecofriendly properties.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mr. Y.B. Sinha, Director (Exploration), and Dr. D. Ray, Executive Director-Head KDMIPE, ONGC for permitting the publication and presentation of this article. The authors are grateful to Mrs. N.J. Thomas, GM KDMIPE, for critically reviewing the manuscript. Views expressed herein are of the authors and not necessarily of the organization they work in.

References

1. Ministry of Petroleum & Natural Gas, "Hydrocarbon Vision, 2025," New Delhi, 2001.

2. Patra, T.C., Pandey, A.K, and Datta, H.C., "Potential areas of India for CBM," ONGC unpub. rep., 1993.

3. Directorate General of Hydrocarbons, "Bidding rounds for CBM—I," Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas, Government of India, New Delhi, 2001.

4. Directorate General of Hydrocarbons, "Bidding rounds for CBM—II, Ministry of Petroleum & Natural Gas, Government of India, New Delhi, 2003.

5. Geological Survey of India, "News," Coal Wing, GSI, Calcutta, Vol. 21, No. 4, 2003.

6. Sharma, D.D., "Review of coal resources in India and their exploration strategy," Jour. Geol. Society of India, Vol. 61, 2003, pp. 387-402.

7. Singh, S.K., Punjrath, N.K., Chakraborty, A., and Peters, James, "Perception of Lignite Bed Methane (LBM) in India," Jour. First APG Conference and Exhibition, Mussoorie, Vol. II, 2002, pp. 317-321.

8. Peters, James, Punjrath, N.K., and Singh, S.K., "Development of coal bed methane resources—challenges in the new millennium," Ind. Geol. Cong, Mar. 16-18, 2001, KDMIPE, Dehradun.

9. Hajra, P.N., Chaudhury, A.T., Biswas, D., Sen, P., and Prasad, A., "A critical assessment of CBM potential of India," Proceed. Petrotech-2003, Vol. 4, KDMIPE, New Delhi.

10. Biswas, S.K., "Prospects of CBM in India," Indian Jour. of Pet. Geol., Vol. 4, No. 2, 1995, pp. 1-23.

11. Bastia, R., Sankaran, V., and Srinivasan, S., "Coal seam methane—its potential in India," Proceedings of Petrotech-1995, Vol. 4, New Delhi, pp. 291-309.

12. Peters, James, and Jamal, Sajid, "CBM potential and prospects in India—A case for diversification," Petrotech-1997, New Delhi, pp. 155-162.

13. Rao, K.L.N, "Resource assessment of coal beds on the Northern Cambay basin, Gujarat, India," International Coalbed Methane Symposium, May 12-16, 1997, Tuscaloosa, Ala., pp. 383-395.

14. Lamberson, M.N., and Bustin, R.M., "Coal bed methane characteristics of Gates formation coals, NE British Columbia: Effects of maceral composition," AAPG Bull., Vol. 77, No. 12, 1993, pp. 2,062-76.

15. Mehta, V.K., "Petrophysical characterization of Barakar CBM Reservoirs of Jharia Basin," Proceed. Petrotech-2003, Vol. 4, KDMIPE, New Delhi.

16. Peters, James, "Evaluation of Coal Bed Methane Potential of Jharia Basin, India," SPE Asia Pacific Paper 64457, Oil and Gas Conference & Exhibition, Brisbane, Australia, 2000.

17. Ministry of Petroleum & Natural Gas, Annual Report, 1997-98.

The authors

James Peters (james_peters@ ongc.net) joined India's state owned Oil & Natural Gas Corp. in 1977. He heads the geology division of KDM Institute of Petroleum Exploration (KDMIPE), the nodal agency for carrying out geological laboratory work for catering to ONGC's exploration and operational needs. He is an M. Tech in applied geology from Roorkee University (now IIT Roorkee).

S.K. Singh ([email protected]) started his career in February 1985 as a geologist in ONGC. Since then he has worked as a sedimentologist and generated data for geological modeling in India's frontier, Bengal, and Assam-Arakan basins. He has an MSc in applied geology from IIT Kharagpur and a doctorate of philosophy in sedimentary geochemistry from Jawaharlal Nehru University.

N.K. Punjrath (nkpunjrath@ rediff.com) joined ONGC in 1983 as a field geologist. He has performed surface mapping and basin analysis in Vindhyan, Satpura, and the Himalayan foothills and has worked as a wellsite geologist in the Assam-Arakan and Cambay basins. He is presently posted in KDMIPE. He has a masters in geology with specialization in petroleum geology from DBS College.