China seeks oil security with new tanker fleet

To guarantee its oil supply during times of crisis, China is building a national tanker fleet with which it aims to haul nearly three fourths of its oil imports within the next 15 years.1 China’s tanker-building program appears to be driven by a complex mix of commercial and national security factors as it seeks control over its entire oil supply chain.

The impact of this fleet-building program on world tanker rates and shipbuilding costs merits the attention of tanker operators worldwide. Paradoxically, however, the buildup of a state-controlled, Chinese-flagged tanker fleet may actually increase that country’s vulnerability to energy supply interdiction.

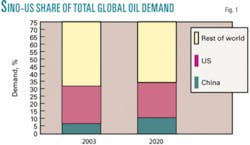

US, Chinese oil demand

Maritime oil transport will be increasingly important for both the US and China in coming decades. As oil demand grows in each country, most of the increase in supply will be met via seaborne imports. As Fig. 1 shows, China’s percentage of world oil consumption is set to more than double in the next 15 years, and combined US and Chinese oil requirements will represent 35% of total global demand by 2020.

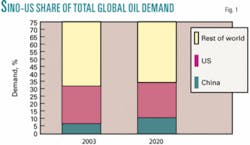

The two countries have very different oil security strategies. The US and most Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development nations emphasize the role of the private sector, whereas China favors a state-led energy policy. Fig. 2 illustrates this divergence, which is a key driver of China’s effort to create a large national tanker fleet.

On the whole, Chinese state oil carriers appear to be following the path of its state oil and gas companies. In peacetime, they will operate for profit. Yet, in an oil crisis, state-owned vessels would stand ready to be pressed into service.

Beijing’s tanker fleet

By 2010, China intends to transport 40-50% of its oil imports in government-owned tankers. By 2020, it hopes to carry 60-70%.2 Chinese analysts predict that by 2010 the country will need as many as 40 very large crude carriers (VLCCs) and a fleet capable of transporting more than 700 million bbl/year.

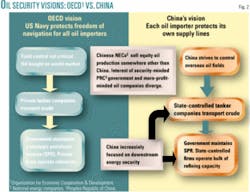

China currently owns 21 VLCCs that cumulatively account for about 30% of its tanker tonnage. Most of the remaining vessels are small or old tankers better suited for the coastal trade than for international oil carriage. Meng Qinglin, a senior manager at Dalian Ocean Shipping Co., estimates that Chinese tankers are on average 30% older than their international counterparts and much smaller, averaging only 20,000 dwt (compared with a typical 300,000 dwt VLCC).3 Fig. 3 shows China’s current oil carriers and their VLCC fleets.

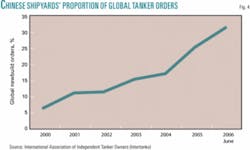

As it upgrades its fleet, China’s aggressive tanker-building campaign has made it one of the world’s leading tanker builders. It also builds smaller tankers, but this article focuses primarily on VLCCs because most Chinese oil imports come from distant areas that require VLCC transport to remain economically competitive. As shown in Fig. 4, Chinese shipyards’ share of new global tanker contracts has grown at an average annual rate of roughly 30% over the past 6 years.

Two primary national security factors drive Beijing’s tanker fleet construction: insufficient overland oil supplies and the fear that terrorists, pirates, or the US Navy could bottleneck its sea lanes.

Overland supplies

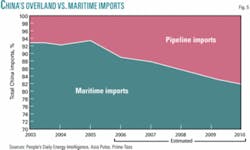

Oceanic oil transportation has become one of Beijing’s chief strategic concerns. Despite a highly touted new pipeline from Kazakhstan and planned lines from Russia, China for the foreseeable future will receive most of its oil by sea. Indeed, many Russian observers believe that without immediately launching a full-scale exploration and production program in Eastern Siberia, Russia likely will be unable to fulfill its oil and gas commitments to China.4

Moreover, although private Russian companies such as TNK-BP are ready to supply China, assertive Russian state-controlled companies hold projects up until they can gain complete control. Russia also fears a repeat of its experience with the Blue Stream gas pipeline, which ran under the Black Sea to Turkey in 2003. Once gas began flowing, Turkey promptly refused to take further deliveries until Gazprom slashed its price, causing the Russian side serious financial losses.

Thus, while overland oil imports from Russia and Kazakhstan likely will continue to grow, they will not solve China’s dependence on seaborne oil. Fig. 5 offers an estimate of trends in China’s pipeline imports that assumes Russia will be able to build and fill a pipeline from Eastern Siberia by 2008.

Chinese leaders find it unsettling that only 10-12% of the country’s imports are carried by Chinese flagged vessels, compared with Japan, which can haul 80% of its oil, and South Korea, which carries 30% of its crude imports.5 Japanese oil transport companies are among the world’s largest, while South Korean and Japanese shipyards have for the last few decades been the world’s premier tanker builders.

Chinese officials are especially concerned that Chinese tankers haul almost none of the cargoes that come from the Middle East and West Africa, which between them supply roughly 70% of Chinese imports.6 In 2002, Chinese tankers carried less than 4% of China-bound cargoes from the Middle East and none at all from West Africa. Some analysts believe that Chinese-operated tankers can better secure oil shipments from unstable areas such as Africa and the Middle East.

Choke-point worries

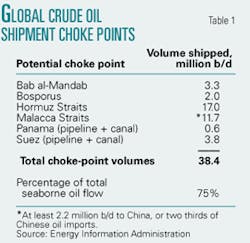

China worries about its present inability to militarily protect the sea lines of communication (SLOCs) and choke points through which much of its oil imports flow, especially the Hormuz and Malacca straits (Table 1).7 Chinese energy security experts have dubbed this the “Malacca Dilemma.”8 They fear that terrorists or pirates could easily cork these bottlenecks, as could the US Navy in the event of conflict over Taiwan or some other serious Sino-American crisis.9

Chinese officials believe that whoever controls the Malacca Strait between Malaysia and Singapore also controls China’s oil and economic security (see map, OGJ, Oct. 18, 1999, p. 23). They concede that in the event of a security disturbance, such as a conflict over Taiwan, China’s inability to secure the strait could be “disastrous” for its security.10

Moreover, the US Navy is not the only threat to China’s maritime energy supply lines. Chinese planners worry that the rapidly modernizing Indian navy could use its naval superiority vis-à-vis China in the Indian Ocean to gain strategic leverage.11 Beijing also casts a suspicious eye on the Japanese Maritime Self Defense Force (JMSDF) because Japan competes with China for energy resources in Russia and the East China Sea and because the JMSDF cooperates with both the US and Indian navies. Japan is interested in the Indian Ocean because most of its oil imports must also transit the Malacca Strait. Japan and Korea both appear comfortable relying on the US Navy to secure their sea lanes, however.

The “Malacca Dilemma,” on the other hand, reportedly is receiving significant high-level attention in Beijing. President Hu Jintao himself advocates revising China’s oil import strategy because “some big countries attempted to control the transportation channel at Malacca.” This strategy could mean a pipeline through Myanmar to China’s Yunnan Province or a “Malacca bypass” pipeline across southern Thailand’s Kra Isthmus.12

Chinese analysts also advocate strengthening the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Navy so that it is capable of “long range rapid responses and interventions in trouble spots” such as Malacca.9 Indeed, Wu Lei, a prominent Chinese energy expert, said, “The fear that the US might cut [energy shipments] off as a result of the deterioration of Sino-US relations over the Taiwan issue drives much of Beijing’s modernization of its navy and air forces.”13

Commercial motivations

Beijing has powerful economic incentives to bolster its shipbuilding sector as well. A large-scale shipbuilding program aids domestic shipyards and the steel industry. It also boosts China’s metallurgical and machine tool sectors. Some Chinese analysts estimate that every 10,000 dwt of tanker capacity built in a Chinese shipyard will create 100,000-200,000 man-hr worth of employment.6 This means that building a single 300,000 dwt VLCC could create up to 6 million man-hr of work. On this basis alone, China’s leadership has a strong argument for supporting its shipbuilders.

A clear indicator that China’s tanker fleet expansion is at least partially driven by commercial interests and concerns is that a significant number of VLCCs are being built in China for foreign operators. These countries thus far include Norway, Iran, Germany, Japan, Venezuela, and Algeria (Table 2). The fact that foreign operators are hurrying to buy Chinese-made tankers also appears to be a vote of confidence in China’s shipbuilding abilities.

Yet, while Chinese shipyards are poised to churn out large numbers of VLCCs and smaller tankers, many Chinese worry that an overly aggressive tanker-building program could raise shipbuilding costs and depress tanker rates. Although China’s oil shippers are state-owned, they appear to operate much like the Chinese national energy producers, many of whom show a strong inclination to emphasize profits over political interests.

Accordingly, a number of analysts propose buying or renting existing tankers in order to save money and reduce the possibility of creating overcapacity in the maritime oil transport market.14 Assuming that China hopes to profit from tanker operations, second- hand ships are indeed a better bet than newbuilds. For example, a second-hand 280,000 dwt VLCC operating on the Saudi Arabia-China route pays out in 9.8 years at World Scale 65 charter rates, while a newbuild tanker would require 14 years to pay out.15 The second-hand ship option seems to be gaining strength, as state-owned Sinotrans Ltd. and other Chinese tanker operators are said to be actively scouring the VLCC market for second-hand ships.16

Fleet structures

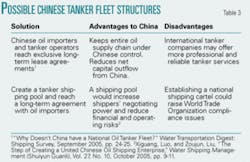

As shown in Fig. 3, seven Chinese companies now possess government-issued crude oil shipping licenses.5 All but two of these license holders are state-controlled.17 The tanker companies may be likened to China’s state oil producers because they compete among themselves yet are collectively expected to act in the Chinese national interest.

Like the state oil companies, it is unlikely that the shippers will be entirely driven by a comprehensive state policy that orchestrates their every move. Some Chinese analysts even suggest that a lack of coordination among the state energy producers and the state energy shippers is partially to blame for the low proportion of crude imports carried on Chinese ships.6 In response, they suggest some potential structures for a national tanker fleet, which are shown in Table 3.

The Chinese government will probably have to give economic incentives such as low-interest loans to Chinese tanker owners to entice them to work more closely with China’s national energy companies. At present, an estimated 90% of China’s oil shipping capacity, or more than 10.8 million dwt, is being used to serve foreign clients.18 This number is significant in absolute terms but would not help China’s long-distance oil transport situation because few of these ships are the VLCCs needed to bring crude from the Middle East, Africa, and other distant locales.

Political obstacles hinder efforts to build a Chinese tanker pool. Bringing Hong Kong shippers into any mainland consortium would help China expand its crude shipping capacity. Yet China’s three main oil producers have so far refused to sign deals with Hong Kong ship owners, claiming that their fleets are “too small.”19 In reality, of Hong Kong’s 72 registered tankers, at least 7 can carry a million bbl or more of crude oil.20 Such ships could economically make long-distance crude hauls that are beyond the reach of the small coastal and shuttle tankers that comprise the bulk of mainland China’s tanker fleet.

How much security?

It appears that, without a substantial blue-water naval capability (likely decades away), China may be painting a bull’s-eye on itself by constructing a state-controlled Chinese-flagged tanker fleet.

China is strengthening its oil transportation capacity to ensure “smooth and uninterrupted” oil deliveries in times of crisis. Yet national tanker fleets do not protect oil importers from the internal security risks endemic to many oil exporting countries. Such instability generally does not affect oil shipments once they get offshore. Rather, many Chinese analysts fear that in a showdown over Taiwan or other crisis, the US Navy and its allies might blockade energy shipments to China.21 However, blockading oil shipments to China would likely only occur if a shooting war had already broken out. A blockade of China would adversely affect the global economy and trigger economic, political, and military alienation of the blockading power.

One way a national tanker fleet might increase oil supply security would be for the PLA Navy (PLAN) to escort Chinese tankers through contested areas. Chinese “hawks” believe that the PLAN must modernize because its ability to secure vital SLOCs and ensure the safety of China-bound oil shipments “seriously lags” behind China’s growing import demand.22 The idea of sending naval forces to escort tankers is hardly unprecedented. When the Iran-Iraq “tanker war” heated up in 1987, the US Navy guarded tankers bringing oil out of the Persian Gulf.

However, without complete PLA naval and air superiority in a given sea zone, carrying oil on Chinese flag ships actually makes the People’s Republic of China (PRC) more vulnerable to energy supply interdiction in the event of a conflict because foreign navies would know precisely which tankers are headed to China. The PRC’s best option might be to rely on private third party tanker operators, whose deliveries could be effectively stopped only by a close blockade of Chinese ports. Such action would expose the blockading state’s naval forces to a wide range of military threats and would almost certainly spark a larger conflict.

An attacker theoretically could try to close Indonesia’s Lombok and Sunda Straits as well, but after a temporary disruption energy shippers would likely find bypass routes to key East Asian markets. By interdicting key choke points, the attacking party might be sacrificing its Asian allies’ well-being and by straining global tanker capacity would also drive up tanker rates for oil consumers around the world. Japan and South Korea have strategic oil stockpiles that, depending on the blockade’s duration, could help them avoid supply shocks. Japan has 92 days’ oil supply in its Strategic Petroleum Reserve, but the Asian and global diplomatic, economic, and political fallout of closing Malacca would be very serious.

Interdicting private tankers at sea also would be tough because it is difficult to determine the true end destination of an oil cargo. In normal commerce, cargoes may be bought and sold several times while still on the high seas. Finally, unless it risked environmental disaster by firing on uncooperative tankers, a blockader would lack the military assets to board and assume control of such ships, as 210 oil tankers/day pass through the Malacca Strait alone.23

Commercial implications

If China builds new VLCCs rather than leasing them, its tanker fleet growth likely will depress global tanker rates and raise shipbuilding costs. This would occur through expansion of the world fleet and increased demand for both shipyard berths and necessary raw materials such as high-grade steel.

The shipbuilding industry will be affected in other ways as well. Chinese shipyards are rapidly gaining operational experience and will be able to tap into China’s vast labor pool and employ thousands of engineering graduates that Chinese universities produce each year.24 China also appears interested in recruiting and training ship crews. Dalian’s Qinglin advocates training a cadre of Chinese mariners to man its tanker fleet.25

Beijing may have to decide whether rapid oil tanker construction is worth the opportunity cost in military shipbuilding. If all the state shipyard spaces are filled with container ships, tankers, and other commercial orders, construction of warships may have to be put on hold.

It is unlikely that China will try to work outside the world oil shipping market because the opportunity costs of doing so are very high. Tanker operations driven by economic opportunity are more profitable than those driven by state directives, and they leave tankers accessible to Beijing in the event of a supply crisis. Similarly, Chinese shipyards’ commercial deals with foreign tanker operators are likely to drive further Chinese integration into the global oil-shipping sector.

The precedent set by China’s national energy companies also favors the adoption of a largely commercial approach to tanker fleet operation. Although China has spent billions of dollars on overseas equity oil acquisitions, state firm China National Petroleum Corp. sells the majority of its equity oil on the international market.26

Further supporting this case, oil from China National Offshore Oil Co. Ltd.’s new Akpo field in Nigeria likely will be sold in Atlantic Basin markets rather than shipped back to China. In sum, China appears to be pursuing a strategy of profiting from shipbuilding and tanker operation during peacetime but hedging its bets against future threats to oil shipments.

Security implications

So long as energy supplies flow uninterrupted, the Chinese tanker fleet will likely operate in a normal commercial fashion. Yet if a terrorist attack or other event disrupts oil production and the Chinese tanker fleet goes out to secure supplies for China accompanied by PLAN escorts, the possibility of naval conflict between China and other countries such as India, Japan, or the US would rise dramatically. Not all Chinese oil security contingencies would involve a Taiwan conflict. An attack on a Saudi export terminal that suddenly tightens world oil markets might be enough to trigger a government “call” on state-run tankers, which would then be given PLAN escorts.

Nonetheless, Chinese worries are substantially misplaced. Unless the US completely closed the Malacca Strait to oil shipments, affecting all East Asian oil consumers and possibly triggering a global oil price spike, there would be virtually no way to interdict private China-bound tankers at a distance from China. The global oil market is highly fungible, ship destinations are unclear because cargoes are often resold at sea, and oil can be transshipped to China through third ports in the region. The same logic applies to the Strait of Hormuz and other oil shipment choke points.

In addition, the number of tankers transiting key choke points would most likely far exceed any potential blockader’s physical ability to control uncooperative ships with means short of disabling fire.

It is hoped that these realities will come to inform energy security policymaking in Beijing and Washington. Global energy security can improve if China overcomes its mercantilist inclinations and relies on the world oil market to fulfill its oil and oil transportation needs. A minority of Chinese analysts, such as Zha Daojiong, now advocates a greater reliance on global energy markets and a turn away from mercantilism.27 Washington would gain by giving China a place at the table through International Energy Agency membership, advising China as it creates a full-fledged energy ministry and strives for a sustainable energy future.

In the meantime, China’s growing oil tanker fleet stands to substantially affect the global oil transportation sector.

References

- Enyan, Qiao, “Petroleum Enterprises and Their Use in National Oil Security Strategy,” Modern Chemical Industry, July 2005, pp. 9-12.

- Ping, Luo, “National Oil, Nationally Hauled: China’s Energy Security Insurance Line,” Maritime China, February 2005, pp. 38-40.

- “Major Chinese Operator Calls for Maritime Oil Transport Development,” BBC, Mar. 10, 2006, Lexis-Nexis, (http://web.lexis-nexis.com).

- “Understandable Expenditures, Non-Existent Profits,” Neftegazovaya Vertikal, No. 7, 2006, (http://www.ngv.ru/magazin/view.hsql?id=3091&mid=119).

- “China taking a firmer grip on energy transport,” Lloyd’s List International, Mar. 3, 2006, (http://web.lexis-nexis.com).

- Xiao, Qin, “China’s Energy Security Strategy and the Energy Transport Problem,” China Energy, Vol. 26, No. 7, July 2004, pp. 4-7.

- Xixing, Lin, “Examining China’s Energy Transport Strategy,” Southeast Asian Studies, No. 2, 2005, pp. 46-50.

- Deqin, Su, Zhang Yongxin, and Huang Lei, “The World Oil Shipping Market and China’s Energy Security,” World Shipping, Vol. 28, No. 1, February 2005, pp.11-14.

- Jie, Li, “China’s Oil Demands and Sea Lane Security,” Jianquan Zhishi, September 2004, pp. 10-13.

- Shaojun, Li, “Mahan’s Sea Power and Its Influence on China’s Oil Security Strategy,” International Forum, Vol. 6, No. 4, July 2004, pp. 16-20.

- Angang, Chen, “Malacca: America’s Coveted Strategic Outpost,” Modern Ship, December 2004, pp. 11-14.

- “China Gives Green Light to Myanmar Oil Pipeline,” Agence France Presse, Apr. 18, 2006, (http://www.uofaweb.ualberta.ca/chinainstitute/nav03.cfm?nav03=45306&nav02=43617&nav01=43092).

- Lei, Wu, Shen Qinyu, “Will China Go to War Over Oil?” Far Eastern Economic Review, April 2006, Vol. 169, Issue 3, p. 38.

branchenverbaende/website_china_state_shipbuilding_corporation;

internal&action=buildframes.action).

Editor’s note: The views set forth in this article are the author’s own and in no way reflect the official views and policies of the US Navy or any other US government entity.

The author

Gabe Collins ([email protected]) is a research fellow in the Strategic Research Department at the US Naval War College in Newport, RI. He is proficient in Russian and Mandarin Chinese, and his main focus areas are Chinese and Russian energy policies, shipbuilding, and Chinese naval modernization. A native West Texan, Collins is a 2005 honors graduate of Princeton University with a BA in politics.