CENTRAL ASIAN OIL AND GAS-1 - China competing with Russia for Central Asian investments

Central Asia has traditionally fallen within Russia’s sphere of influence, but as China seeks oil and gas to fuel its energy-hungry economy the growing level of Chinese energy investment in Central Asia is challenging Russia’s economic dominance in the region.

A worldwide search for oil and gas reserves has returned to China’s own neighborhood, with Chinese oil companies stepping up their involvement in Central Asia in 2005.

China’s increasing attention to Central Asia has the potential to threaten Russian preeminence in its “near abroad,” but Russian oil and gas companies are responding to the challenge by increasing their own investments in Central Asia.

Competition between Russian and Chinese oil companies for oil and gas reserves in Central Asia is on the rise, but collaboration on several projects, as well as direct bilateral cooperation between the Russian and Chinese governments, could help ensure that the nascent rivalry remains benign.

Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan should benefit from the rising levels of investment in their energy sectors by Russia and China, but the overall effect may be to marginalize the US and European governments in their attempts to bring about political and economic reforms in the Central Asian countries.

Not in my backyard

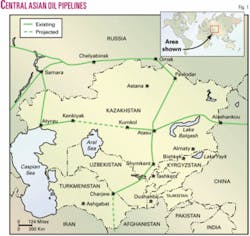

With the December 2005 commissioning of an oil pipeline connecting Kazakhstan to China, the missing link in China’s chain of investments in Central Asia was put in place, both literally and symbolically.

The launch of Kazakh oil flows toward China along the Atasu-Alashankou stretch of the pipeline represents the culmination of a strategy that has seen China increasingly target the Central Asian republics of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan for energy sector investments.

China is looking far and wide for access to oil and gas reserves to fuel its booming economy, but the focus on Central Asia’s oil and gas in China’s backyard is a relatively recent phenomenon.

The fact that China has begun to look to invest in energy resources closer to home is not earth-shattering in itself-after all, transportation costs should be lower than importing oil and gas from more distant locales-but the particular focus on former Soviet Central Asia is certainly newsworthy.

Over the course of the past 130 years, the region has been chiefly Russia’s domain. From the tsarist period and Soviet annexation to Stalin’s haphazard drawing of republic borders through to the collapse of the Soviet Union, the “stans” have traditionally fallen under Russia’s sphere of influence.

Even though the Central Asian republics became independent in 1991, Russia has continued to wield significant authority in the region, which Russians consider the “near abroad.”

Russia has maintained a strong say in the affairs of the Central Asian republics, in large part due to its control over the region’s oil and gas export exports, which are a major source of revenue for Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan, in particular.

Until 1997, when a gas pipeline linking Turkmenistan to Iran was put into operation, the Central Asian countries were completely dependent on Russia as a market or a transit state, as all oil and gas export pipelines from the region were routed via Russia.

The risk of this dependency was made clear in the 1997 dispute between Turkmenistan and Russia over gas prices when Gazprom refused to take any Turkmen gas from the Central Asia-Center (CAC) gas pipeline, causing Turkmenistan to shut in gas production and exports. The result of the price row was a 25% contraction in Turkmenistan’s economy, although the Korpezhe-Kurt Kui pipeline linking Turkmenistan to Iran was also born out of the dispute.

Turkmenistan remains almost entirely dependent on Russia as an outlet for its gas exports, both as a destination and a transit state, and Gazprom has effectively blocked Central Asian gas exporters from accessing the lucrative European market.

Turkmenistan does have a gas supply deal with Ukraine (albeit a deal marked by animosity) that depends on Gazprom compliance as a transit partner, but the Russian energy giant has reclaimed the Caucasus markets for itself, cutting Itera, which had carved out a niche for itself as a gas trader supplying Turkmen gas to Georgia and Armenia via Russia, out of the market.

Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan have also sought to monetize their gas reserves by emphasizing exports, but both countries have been essentially thwarted by Gazprom in attempting to expand to markets beyond the Central Asian region.

A deficiency of pipeline infrastructure means that the vast majority of Central Asian gas is piped into the CAC pipeline, which feeds into the Gazprom network, while the lack of market options means that Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Kazakhstan are forced to sell their gas at cut-rate prices into the Russian market in order to secure any value from their gas reserves.

Uzbekistan also sells some of its gas to Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan as well as southern Kazakhstan, but these deals are typically paid at least partially in kind, and the cash value of the deals is well below the actual “market” value.

Likewise, Russia exerts considerable leverage over Central Asian oil exports, with the bulk of the region’s growing volume of oil production directed via the Russian pipeline system.

Until the launch of the Kazakhstan-China pipeline, Kazakhstan was reliant on Russia for its two major oil export routes, the Atyrau-Samara pipeline and the Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC)’s Tengiz-Novorossiisk pipeline. A small amount of oil from Kazakhstan, as well as Turkmenistan, is shipped by barge across the Caspian for further transshipment by rail across Azerbaijan and export from Georgia’s Black Sea ports.

The disadvantages of Kazakhstan’s dependence on Russia as a transit state were made plainly evident with Russia’s refusal to allow the CPC to expand from its initial 565,000-b/d-capacity to the planned 1.34-million b/d until shareholders consented to a Russian-demanded increase in the transit tariff for the pipeline.

Even though the other CPC shareholders agreed to a transit tariff increase, Transneft, the Russian oil pipeline operator that holds a 24% stake in the CPC on behalf of the Russian government, is now holding the other pipeline shareholders hostage with a demand to make any expansion of the CPC contingent on shareholders’ support for a plan to build a “Bosphorus bypass” pipeline to connect Bulgaria and Greece.

Transneft’s refusal to transport crude from Kazakhstan to Lithuania despite a transit agreement cast Kazakhstan’s predicament in sharp relief.

Thus, Russia’s effective control over Central Asia’s oil and gas export infrastructure has translated into substantial leverage over the economic development of the “stans” in the post-Soviet era. Russia’s historical dominance of Central Asia has become a somewhat self-perpetuating concept, with the European Union (EU) and the US largely shying away from substantial involvement in Central Asia in the 1990s lest they be accused of seeking to invade Russia’s sphere of influence.

Turkey briefly sought to challenge Russia by highlighting the religious and linguistic ties with the Muslim states of Turkic Central Asia, but Turkey’s own preoccupation with the EU and its drive to orient itself to the West left Russia as the main power broker in Central Asia.

However, the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks in the US forced a change in the status quo, making Central Asia suddenly relevant on a global scale. The impact of those attacks-and the determined retaliation by the US against the Taliban and al-Qaeda in Afghanistan-essentially opened Central Asia to competition for influence, especially with the establishment of US military bases in Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan.

Although Russia initially consented to the US air bases, their continued presence in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan-along with an enhanced interest by the US and European governments in Central Asia’s political development-has made Russia increasingly nervous and uncomfortable about intruders in what it considers to be its backyard.

Enter China

In the context of a nascent attempt by the West to engage in Central Asia and loosen the Russian stranglehold on the region, a separate challenge from the East has flown under the radar.

In the past few years and particularly in 2005, China has stepped up its involvement in Central Asia, in particular by investing in energy projects in the region. China’s increased attention to the countries on its western border can partly be explained by the war on terror and a focus on ethnic issues with the Uighur population, but China’s obsession with securing oil and gas resources to feed the country’s growing demand has made Central Asia an even more attractive target for investment.

China has taken a largely state-led approach to investing in Central Asia’s energy resources, and its government has signed a series of bilateral energy sector “cooperation” deals in the region. These general state-to-state agreements, however, have served to build a foundation of intergovernmental trust upon which Chinese state-owned companies have successfully carried out investments in several major upstream hydrocarbon projects, especially in Kazakhstan, but also increasingly in Uzbekistan.

Moreover, China and Turkmenistan are poised to strengthen their ties and establish the basis of a relationship that could see Turkmen oil and gas eventually delivered east to China.

Kazakhstan

Considering that it borders on China and has the largest proven oil reserves in Central Asia, it is not surprising that Kazakhstan has been the main focus of Chinese energy investment thus far.

Until 2005, the largest Chinese venture into Kazakhstan’s energy industry was Aktobemunaigaz, a western Kazakhstan production company in which the China National Petroleum Corp. (CNPC) has amassed an 88.25% stake.

CNPC-Aktobemunaigaz produced 106,000 b/d of oil in 2004, and in 2005 the joint venture announced the discovery of Umit oil field after extensive seismic exploration. CNPC-Aktobemunaigaz also has the rights to the Zhanazhol and Kenkiyak deposits.

China National Offshore Oil Corp. (CNOOC) and China Petroleum & Chemical Corp. (Sinopec) each made a bold bid in 2003 to gain entry into the massive Kashagan offshore project in the Kazakh sector of the Caspian Sea. However, after securing separate deals to buy equal 8.33% stakes from BG for $615 million each, CNOOC and Sinopec were blocked from joining the international consortium developing the elephant field when Western members exercised preemption rights.

Although the move by the international oil companies to shun CNOOC and Sinopec provoked a fierce stand-off with the Kazakh government, the Chinese companies remained on the outside of the Kashagan project looking in.

In its place, Sinopec, CNPC, and CNOOC have instead gone about their business mostly under the international radar screen, steadily acquiring acreage in western Kazakhstan and on the Caspian shelf.

In September 2003 CNPC acquired the rights to North Buzachi field, which while disappointing in its output nevertheless represented another producing asset.

As the Chinese companies accumulated actual and potential oil production, the concept of a potential trans-Kazakhstan oil pipeline to China previously dismissed as uneconomic gained credence. When CNPC agreed to fund and fill the planned 400,000-b/d-capacity pipeline, work quickly moved ahead on the link.

The 1,000-km, $700 million Atasu-Alashankou pipeline, which links central Kazakhstan to the Kazakh-Chinese border, was officially launched in December 2005, less than 16 months after construction began.

The pipeline, actually Phase Two of a three-part pipeline that will eventually connect Caspian shelf oil production to China, provides Kazakhstan with a non-Russian oil export alternative route for the first time. However, the Atasu-Alashankou conduit is not expected to reach its initial export capacity of 200,000 b/d until the end of 2007, while the third phase of the pipeline, to link Kenkiyak in western Kazakhstan to Kumkol in central Kazakhstan, is not slated to kick off until 2011.

In the interim, CNPC has made sure that it will have enough oil to supply to the pipeline through its acquisition of PetroKazakhstan, the 150,000-b/d Canadian-based producer. However, the deal was nearly derailed as the Kazakh government moved to assert greater control over its hydrocarbon industry, including limiting the transfer of property rights-even between foreign companies-to “strategic” energy resources in Kazakhstan.

CNPC rescued the transaction by consenting to sell a 33% stake in PetroKazakhstan to Kazmunaigaz, the Kazakh state oil and gas company, as well as agreeing to up a 50-50 joint venture with Kazmunaigaz to operate PetroKazakhstan’s Shymkent refinery in southern Kazakhstan.

The launch of the Kazakhstan-China oil pipeline and the acquisition by CNPC of PetroKazakhstan have by no means satiated the Chinese appetite for energy investments in Kazakhstan. Indeed, the Kazakh and Chinese governments are continuing to explore the possibility of laying a gas pipeline linking the two countries in parallel with the oil pipeline.

CNPC and the other Chinese state oil companies remain on the hunt for additional Kazakh oil assets, and reports have already surfaced linking CNPC to a potential bid to acquire 50,000-b/d Canadian producer Nations Energy.

Moreover, joint plans by Kazakhstan and China to build a $4 billion coal-fired power plant at Ekibastuz near the Russian-Kazakh border show that China’s energy interests in its neighbor stretch beyond merely oil and gas.

Next: China and Russia compete and collaborate on Central Asian oil and gas projects, possibly marginalizing US, European influence. ✦

Updated from “Central Asia: Whose Backyard? China Competes with Russia for Central Asian Energy Investments,” by Andrew Neff, Global Insight, Jan. 9, 2006.

The author

Andrew Neff ([email protected]) is a senior energy analyst at Global Insight, focusing on the Commonwealth of Independent States, the Baltics, and Balkans, with special emphasis on Russian and Caspian Sea oil and gas. Before joining World Markets Research Centre (now Global Insight) in 2002, he worked as an international energy analyst, first from Washington, DC, then from Kiev, Ukraine, for a contractor to the Energy Information Administration, the statistical division of the US Department of Energy. He holds an MA in international affairs and environmental policy from George Washington University’s Elliott School of International Affairs.