Appalachian basin’s Devonian: more than a ‘new Barnett shale’

Recent reports on the successful development of Devonian organic shale reservoirs in southwestern Pennsylvanian and adjacent West Virginia have raised the speculation about this reservoir.

Both the nonindustry media and investment brokers and money managers have recently promoted the notion that the Appalachian Devonian is the “new Barnett Shale.” The purpose of this article is to refute this claim and to explain why development of the Devonian holds potential beyond that seen in the highly successful Barnett shale.

Geologic setting

The Catskill Delta of the northern Appalachian basin is composed of a complex of predeltaic and deltaic sedimentary rocks of Devonian age.

Lower Devonian rocks are generally considered to be pre-Catskill Delta. They consist of interbedded limestone and sandstone reservoirs; the most famous of these reservoirs is the Oriskany formation. The Oriskany has gone through numerous phases of development and most recently has been developed for natural gas storage.

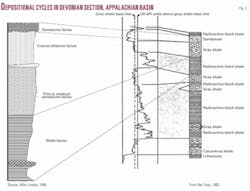

Traditionally, the Catskill Delta consists of Middle and Upper Devonian black shales. The stratigraphy of this interval is shown in Fig. 1 along with a location map that identifies the areas of interest in Pennsylvania and New York.

Part of the problem in evaluating the Devonian of the northern Appalachian basin is that many local names for the reservoirs have been imported from Ohio and West Virginia; this causes regional correlation to be confused.

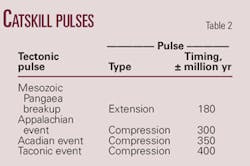

Essentially, there were four pulses of deposition associated with the Catskill Delta (Table 1). Natural gas production is found in both the Middle and Upper Devonian. In previous papers, the author has described where production in New York is found. Van Tyne1 provides a detailed discussion of the potential of Devonian reservoirs in New York.

Most recent developments in Pennsylvania (and West Virginia) involve the Marcellus member of the Hamilton Group. In these areas, erosion or nondeposition has caused much of the Upper Hamilton Group (or equivalent) to be lost; only the Marcellus member remains to be successfully developed.

The core of the Catskill Delta (and its Pennsylvania coequivalent) is found in the eastern third of the respective states. The members of each depositional pulse are thicker and more developed as one travels eastward, increasing the potential for source rock and reservoir horizons to form.

Recent work by Linsley2 and others has suggested that there is a cyclical nature to each pulse of deposition (Fig. 2). Each general cycle includes organic shale overlain or interbedded with siltstones and sandstones; this coincides geologically with the types of sediments that should be found with an emerging delta.

It also suggests that sandstones and siltstones (with reservoir potential?) lie in proximity to organic shale source rock. This is dissimilar to the lithology and sedimentology of the Barnett shale. It implies that different reservoirs will be found in the Devonian of the Appalachian basin.

The author understands that the Barnett ranges from 200 to 800 ft thick at depths of 5,000 to 15,000 ft.3 Both Upper and Middle Devonian rocks of the northern Appalachian Basin vary in thickness, depending especially upon location relative to the delta. Middle Devonian rocks can vary in thickness from 500 ft in along the western edge of deposition to 3,000 ft closer to the delta.

Depth to pay can range from less than 1,000 ft to more than 5,000 ft relative to the position of the delta. This implies that lower drilling costs for Devonian wells should be expected. Fracturing or artificial stimulation is necessary to produce the Barnett; special programs have been developed specifically to enhance production in this reservoir. Remote sensing studies completed by the author have identified four tectonic pulses that have created natural fracturing (Table 2). Each of these events caused tectonic stress that created secondary porosity and permeability in both source rock and reservoirs.

While the bulk of the compression/extension was located to the east of today’s basin (i.e., the area of interest), it did enhance reservoir development and could aid recovery and reduce postdrilling engineering costs.

In addition to geologic and engineering conditions, there is one other important difference between the Barnett and the Devonian plays. The Barnett is one of a number of Midcontinent plays that supplies gas to a relatively limited marketplace.

The Devonian of the Appalachian basin, when fully developed, has the potential to supply gas to an area from Boston to Richmond. This represents 60% of the population of the US, and is generally speaking an area in which gas is not the primary choice for residential and industrial heating (i.e., there are plenty of marketing opportunities).

Further, when the resource is developed, New York gas will service New York City and its suburbs through intrastate pipelines that avoid FERC pricing and transportation charges. The same can be said for Pennsylvania gas distributed through eastern Pennsylvania. This suggests that traditional economic models based upon large volume reserves would not be applicable to this play.

Instead, lower volume long-lived reservoirs could be quite profitable. A number of producers in the northern Appalachian basin operate low volume wells that have been around for over 75 years, and they show profit above operating costs.

The relatively simplistic analogy of the Devonian shale being the “new Barnett” is wrong. This may be a promotion to encourage investment, but technically it is not true and in fact could be purposely misleading. The Devonian of the Appalachian basin is a complex geologic interval that hosts potential for the future.

Some analysts suggest that the Appalachian basin could hold in excess of 200 tcf of gas in place. Development of the reservoir will require astute geologic analysis, basin specific engineering, and the ability to create knowledge of the subsurface by drilling wells. There are no shortcuts here.

The reservoir potential is present, the infrastructure is in place, and the marketplace awaits success. In this author’s opinion, the Devonian of the Appalachian basin isn’t the new Barnett; it’s better!

References

- Van Tyne, Arthur M., “Natural gas potential of the Devonian black shales of New York,” Northeastern Geology, Vol. 5, Nos. 3-4, 1983, pp. 209-216.

- Linsley, David M., “Coarsening-up cycles and stratigraphy of the upper part of the Marcellus and the Skaneateles formations of Central New York,” in “Dynamic stratigraphy and depositional environments in the Middle Devonian Hamilton Group of New York,” Part 1, New York State Museum Bull. 457, 1986.

- Riestenberg, D., Ferguson, R., and Kuuskraa, V., “New and emerging unconventional gas plays and prospects,” OGJ, Sept. 24, 2007, p. 48.

Bibliography

New York State Energy Research and Development Authority, “Shale gas in the south central area of New York,” Vols. 1, 2, and 3, 1981.

Pyron, Arthur J., Viellenave, Jim, and Fontana, John, “New York Devonian black shale: A Barnett-like play in waiting,” OGJ, Jan. 13, 2003, p. 36.

Pyron, Arthur J., “What Exactly Is Happening in the Appalachians?,” SIPES Newsletter, Vol. 39, No. 2, 2001, p. 1.

The author

Arthur Pyron ([email protected]) is sole proprietor of Pyron Consulting, Pottstown, Pa. He has 28 years of geological and business expertise in a variety of exploration and development programs. He has an MS in geology from the University of Texas at El Paso.