Norway remains active, UK seeks change

Tayvis Dunnahoe

Exploration Editor

Like most offshore regions, the North Sea is experiencing a temporary slowdown in exploration and development (E&D). Predominant activities in the near term include development drilling and some minor seismic work. While Norway's production has remained relatively stable, output from the UK Continental Shelf (UKCS) has continued to decline.

Although E&D opportunities remain offshore Europe, low oil prices are testing the industry's resilience. The North Sea's status as a mature basin draws operators wanting to take advantage of the certainty in developing discoveries near existing fields and infrastructure. Limited profitability and the lack of investment in the region, however, are leading operators to venture outside such areas to test regions with more viable development potential.

Offshore activity in Europe remains concentrated in Norway and the UK. But as drilling has slowed in the last few years, no major discoveries have occurred in the North Sea. Smaller countries in northwest Europe, such as Ireland and the Netherlands, are maintaining their assets during the down cycle, but it is likely that major exploration programs will remain deferred until the industry realizes stable, higher prices for oil and natural gas. In the Mediterranean, Greece and Cyprus have giant offshore gas deposits with future E&D potential. But given current pricing, operators have postponed these developments until further notice.

According to analyst Ben Wilby of Douglas Westwood, shorter term activity in the region is moving forward as operators follow through on commitments, but this may not be an indication that the market has improved. "Offshore Europe will look busy, but in practice, most of the current activity was ordered before the price decline," he told OGJ.

Norway

In 2013 global exploration yielded 142 discoveries. The number of discoveries dwindled to 62 in 2015, of which 15 were offshore Europe and most were small deposits discovered in Norway near existing fields. "Norway's existing fields and infrastructure makes this region better suited for development drilling than elsewhere offshore Europe," Wilby said. "Companies have moved to where they know they can find success."

Norway's offshore activity will remain stable, but discoveries are often small. "The average discovery size in the Norwegian North Sea from 2011-15 was just 34 MMboe," Ed Shires, senior consultant with London-based consulting firm StrategicFit, told OGJ. "In the 5 years before this (2006-10), the average was 145 MMboe," he added. This number includes the 1.9 billion boe Johan Sverdrup field (OGJ Online, June 6, 2016). Excluding this discovery, the average was 50 MMboe/field.

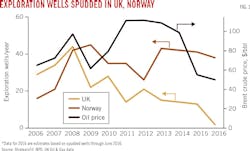

Operators have spudded 18 exploration wells offshore Norway so far in 2016. "If this rate carries into the second half of the year, this will be in line with trend," said Chris Jones, senior consultant with StrategicFit. Since 2008, with the exception of 2012, Norway has seen 35-45 wells spudded each year (Fig. 1).

The Northern North Sea (Quads 31, 32, 34, and 35) has been the most active area on the Norwegian shelf with 12 of the 18 wells drilled this year (OGJ Online, June 10, 2016). "This is a relatively mature area in easy reach of infrastructure at the Oseberg, Troll, and Gjoa fields," Shires said.

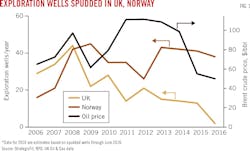

In Norway, the tax system is set up so that companies only pay 22% of their exploration costs. The rest is refunded by the state. This, along with greater yet-to-find volumes, makes exploration in Norway more attractive than other regions, including the UK.

Norway suffers from high capital costs. But some newer and larger fields, along with numerous subsea installations, will make operating costs more competitive over time.

Norway sometimes struggles to attract exploration investment when companies compare the country to other regions, according to Shires. Operators often evaluate opportunities on a pretax basis. Norwegian opportunities become favorable only after factoring in the exploration tax rebate: finding costs were $8/boe pretax, $1.7/boe after tax (2011-15). "When considering developments, the tax drag on full-cycle returns may still reduce the region's attractiveness," Shires said.

Meanwhile, "frontier drilling has dropped off the map completely," Wilby said. Development may lag in the Barents Sea Arctic region as economic success requires a stable oil price of $80/bbl. Long lead-times (10+ years) for Barents Sea Arctic projects will likely allow companies to benefit from the evenatual price recovery.

The recent 23rd Licensing Round in the Norwegian Barents Sea showed frontier opportunities are attracting interest despite low oil prices. The Norwegian Barents Sea produced four of the five largest discoveries in Norway during 2011-15. There were four firm wells committed in the newly offered acreage in the East Barents (on the Russian Border), despite high commerciality thresholds of 0.5 billion boe of oil or 6 tcf of gas.

"Some explorers are taking a long-term mindset, and are looking to find large discoveries in relatively undeveloped areas of Europe despite no quick commercialization pathway," Jones said. The companies who were awarded licenses in the region are experienced Barents Sea operators (Statoil ASA, Det norske oljeselskap AS, Lundin Petroleum AB) and supermajors (ConocoPhillips, Chevron Corp.).

"It is not yet clear if any of these discoveries are large enough to warrant new infrastructure," Shires said, referring to four of the five largest discoveries in the region. The Johan Castberg discovery (0.6 billion boe) is subject to delays and development remains uncertain (OGJ Online, Mar. 6, 2015).

"Projects are not being sanctioned now, leading to a decline in spend in the last few years of the decade," Wilby said, but 2019 could see an increase in newly sanctioned projects. Aasta Hansteen, Europe's first spar platform, is one of the largest projects headed for first production in the near term. But this development was committed to before oil price fell.

Statoil in August 2015 completed construction of the 482-km Polarled pipeline to connect to Aasta Hansteen (OGJ Online, Aug. 21, 2015). The operator cancelled its contract in May 2016 for Seadrill Ltd.'s West Hercules semisubmersible drilling rig, which was scheduled to begin drilling on the Aasta Hansteen license in 2017 (OGJ Online, May 23, 2016). Statoil has pushed Aasta Hansteen's start up to first-half 2018.

Norway's economy has been hit hard as oil provides 22% of the country's GDP and 67% of its exports. "The price drop is having a bigger impact than the 2008 financial crisis," Shires said.

UK

The oil and gas industry in the UK is struggling to remain competitive. High operating costs, aging infrastructure, and a lack of recent discoveries contribute to the region's problems. Only one exploration well has spudded in the UK in 2016 (Fig. 1). "Exploration drilling in the UK has not recovered from the last oil price dip during 2008-09," Shires said. Well spuds fell to 22 in 2009, down from 44 in 2008. Since 2011, well spuds have remained at 15-20 per year. The impact of lower prices was not fully realized in 2015 as the UK saw 13 wells spudded. "These were probably planned and approved before the full price drop, which is now reflected in the lack of drilling in 2016," Shires said.

The UK North Sea decline is not a new problem. ConocoPhillips drilled 10 UK exploration wells in 2006 and a single well in 2011. Shires attributed this to the company's strategy of focusing on its onshore operations in other regions. Total viewed the UK as a high growth area in 2011-12, but its high risk exploration strategy was unsuccessful. "Now only one of more than 30 of Total's high impact wells (2016-18) is in the UK," Shires said.

Producing oil and gas in the UK comes at a higher cost per barrel than in other offshore regions (Fig. 2). Operating costs are driven by aging infrastructure with low throughput and capital costs are compounded by high labor and engineering costs combined with typically small fields.

Operators historically have worked to extend the life of offshore fields in the UK. Redevelopment continues to be an option but maintenance costs, new recovery techniques, and upgrades can become expensive. Operators in the UK may shut in production below $50/bbl. "Rig rates are cheaper now, and infill drilling may be advantageous for some UK fields," Wilby said.

According to IHS's Upstream Capital Cost Index, global cost base fell 21% between the fourth quarters of 2014 and 2015. Rig rates for northwest Europe jack ups are down to $100,000/day from the mid-2014 high of $175,000/day. "These effects will be felt globally so northwest Europe may remain comaparitively expensive," Shires said.

Some UK projects are moving ahead. EnQuest PLC expects first production from its Kraken fields in first-half 2017. The development includes a floating production, storage, and offloading vessel with 25 development wells (OGJ Online, Feb. 22, 2016).

Capital constraints will continue to affect new development as part of UK North Sea operations. "Less than $1 billion of new capital is expected to be committed in the UK in 2016," Shires estimated. The $8 billion/year average since 2011 shows the extent to which projects are now being deferred.

In Norway, third-party access to infrastructure is guided by commercial negotiation, with voluntary practices and an ability to refer disputes to the secretary of state. This is not the case in the UK, which makes it difficult for companies to agree on commercial terms. The establishment of UK's Oil and Gas Authority (OGA) may foster more collaboration, which will be required to sustain the country's offshore industry.

The UK changed its fiscal regime in the wake of the price decline. "The Petroleum Revenue Tax for pre-1993 fields, which was 50% at the start of 2015, has been effectively abolished," Shires said. Additionally, the supplementary charge companies pay above corporation tax has been cut to 10% from 32%.

"The impact of these tax changes is questionable, given the tax is levied on profits," Shires said. Only three companies operating in the UK were profitable in 2015. Companies also have losses to offset future profit, which will defer tax payments once profitability returns. The benefits of the UK's new tax regime will not be felt in the near term. "Norway's effective exploration rebate has been more effective in sustaining drilling," Shires said.

By contrast, where the price decline has negatively impacted Norway's economy, the UK's economy is expected to benefit from "lower-for-longer" oil prices, which will lower the cost base for other industries.

Development vs. decommissioning

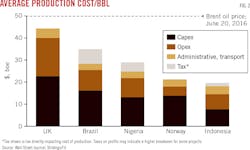

For aging assets in the UK and Norway, lower oil prices are forcing operators to decide whether to redevelop mature fields or shut in current production in preparation for decommissioning (Fig. 3).

"The UK dominates in fixed platforms with around 300 of these assets compared to Norway, which has around 100," Wilby said. "UK production is mature and companies are not producing the same amounts of oil and gas they were 10 years ago," he added.

The UK is expected to be the first major petroleum province to see widespread decommissioning. "Five fields have already been announced to cease production in 2016," Shires said. More than 140 fields could follow in the next 5 years if prices remain low and cause older fields to become uneconomic.

"The UK will need to strengthen its parameters on decommissioning to avoid additional expense as this trend continues," Wilby said. The country currently offers a 50% rebate on decommissioning. A ramp up in decommissioning to 2020 could further burden the UK tax base. "Now is the time to decommission," Wilby said.

Decommissioning initially costs more than maintaining a facility, but it's a onetime expense. If the price for oil remains low for an extended period of time, maintenance and overhead could override the lump sum attributed to decommissioning.

Development continues in Norway and decommissioning may not occur to the same extent as in the UK.

Turning around

PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP (PwC) surveyed leading executives and academics associated with the North Sea's offshore oil and gas industry in its report "A Sea Change: The Future of the North Sea Oil & Gas," which was released June 2016.

Respondents agreed that the window of opportunity to transform North Sea business is slowly closing. Alison Baker, leader of PwC's UK and EMEA (Europe, Middle East, and Africa) oil and gas team, said, "The North Sea is one of the oldest producing basins in the world and has contributed to the European economy for more than 50 years." Companies must determine how, or if, they will work together as they either decommission or maintain aging infrastructure and move forward with further extraction while competing for capital with lower-cost basins having greater returns.

"Norway is a different play, and participants were more optimistic, as opportunities exist in this region," Baker said. The South and Central North Sea are the regions losing momentum in the current downturn. In reference to the window of opportunity, Baker said, "The impetus is on the speed at which the industry transforms. Collaboration needs to occur more often and more quickly."

The major concerns from the UK perspective, according to the respondents in the Sea Change report, are access to capital and getting costs under control, including improved technology and innovation. "The UK has produced 42 billion bbl of oil, and there are some 20-30 billion boe of undiscovered resources," Baker said. Opportunities exist, but financing has become constrained. For UK exploration, equity financing "dried up around 5 years ago," she added.

The concept of "super joint venture (JV)" was introduced by several respondents in the report. "The concept relies on looking at other basins and industries where operating models were reinvented through crisis," Baker said. Cost sharing, improved supply chains, and sustaining access to infrastructure are key objectives of the concept.

UK operators and field partners must carry the full cost of servicing or decommissioning. A super JV could develop cost-sharing mechanisms to maintain current production assets in exchange for future access.

"We believe the UK represents an opportunity to build a new model for commissioning the final cycle in a mature basin," Baker said. Finding new methods of collaboration can transfer knowledge to other basins. "Tried and tested ways of working together in the final phase of UK North Sea development will provide a model for other regions in the future," she added.

The recent Brexit referendum has added a layer of uncertainty to UK North Sea operations given the oil and gas industry's global nature, raising confidence in the UK economy to the fore (OGJ Online, June 27, 2016). According to Baker, "The industry has remained resilient and wants to work together to maintain it's activities in the UK."

Opportunities, outcomes

The offshore industry across Europe is struggling in the current down-cycle. The UK sector has lost more than 100,000 jobs. Job loss is at 40,000 in Norway (OGJ Online, June 20, 2016). Despite the increased demand for natural gas in Europe, both oil and gas projects are struggling. Operators are generally exploring for oil over gas, and in frontier regions such as the Barents Sea and West of Shetland, initial infrastructure for gas is cost prohibitive. "All but the biggest projects are uneconomic," Shires said.

Despite the situation in the UK North Sea, frontier basins in other portions of the European Continental Shelf are generating interest.

Frontier drilling is down in the near term as companies cut back costs, but many operators see frontier regions as a source of material discoveries in northwest Europe. As a result, offshore acreage is being picked in areas like the Barents Sea and Ireland as interest in exploration remains high among companies with capital to invest.

The 2015 Atlantic Margin licensing round had the highest number of applications for any Irish offshore round (43) and 28 new licenses were awarded. The offer of awards involved 11 companies: AzEire Petroleum Ltd., Capricorn Ireland Ltd., Europa Oil & Gas (Holdings) PLC, Faroe Petroleum Ltd., Petrel Resources PLC, Predator Oil & Gas, Providence Resources, Ratio Petroleum, and Scotia Oil & Gas Exploration Ltd., as operators, along with Theseus, which will partner with Predator, and Sosina Exploration Ltd. which will partner with Providence.

The first half of this round, announced February 2016, included Woodside Energy (Ireland) Pty. Ltd (OGJ Online, Feb. 15, 2016). The operator began seismic work on its Granuaile prospect (Petroleum Production License (PPL) No. 2/16) with the Ramford Vanguard (Fig. 4). The vessel was expected to shoot 1,600 sq km of 3D seismic through late June. An additional seismic shoot is slated for Woodside's Breanann prospect, the Ramford Vanguard scheduled to acquire 2,400 sq km of 3D seismic over Frontier Exploration Licenses (FEL) 3/14 and 5/14 (Fig. 5). Weather permitting, the acquisition is expected to be completed in late August 2016. The blocks are in the Porcupine basin 150 km off the west coast of Ireland.

No exploration wells have been committed, but the attraction to Ireland's 2015 round indicates that commitments may be on the horizon. Operators have drilled 159 exploration and appraisal wells offshore Ireland since 1970. There have been four commercial gas discoveries and 11 oil and gas condensate discoveries. None of the latter discoveries have led to commercial development.

In the UK, more than 4,000 wells have been drilled, resulting in more than 350 producing oil and gas fields. In Norway, more than 1,200 wells have been drilled. The contrast highlights the underexplored territory offshore Ireland.

The deepwater West of Shetland and North Sea high pressure, high temperature (HPHT) plays present additional opportunities. But the HPHT environment increases exploration costs. "This area could present a counter cyclical opportunity," Shires said, "but this would require a unique risk-appetite and access to capital."

The need for such an appetite is highlighted by the reality that exploration budgets have shrunk. "A number of exploration managers believe the HPHT play has great petroleum potential, and many operators would have liked to explore there," Shires said. Despite falling rig rates, however, most operators cannot justify this play's well costs.

One benefit of this down cycle and the onslaught of deferred offshore projects is the closer attention operators have paid to spending. Costs tend to sky rocket in a stable oil price environment and by early 2014 were too high for development once the price declined.

"Companies are now looking at standardization as a means of lowering costs," Wilby said. In addition to standardization, the lull in offshore activity has given operators and service contractors opportunities to revisit newer production designs and reengineer projects within current cost constraints.

The most recent example of this is Statoil's Snorre field (Fig. 6). In 2013, the operator ordered an additional tension leg platform (TLP) to increase recovery from the field (OGJ Online, Oct. 28, 2013). After the price shock of mid-2014, the TLP field expansion became uneconomic and earlier this year was scrapped and exchanged for a subsea development plan (OGJ Online, Apr. 25, 2016). The change is expected to save 30-40% and boost recovery from Snorre field to 2040.

Lack of investment in North Sea infrastructure and near-field exploration now could lead to lost opportunities in the future. Hubs and pipelines may become uneconomic before surrounding prospects have been exploited. "This is especially so in the UK, where much of the infrastructure is interlinked," Shires said. "A 'domino effect' might occur where production ceases on one field forcing others further down the infrastructure chain into early abandonment."

Near-term operation

The current downturn has led to returns of offshore licenses, globally. Asset swaps are becoming more common as larger companies look to rationalize their portfolios and reduce European assets. Many small- to mid-sized companies will enter the offshore market in Europe in the next few years.

The region benefits from active regulators and regularly occurring license rounds, which provide frequent opportunities for organic growth. "License commitments are followed up, which churns viable exploration acreage and avoids dormancy," Shires said.

UK's OGA is working to ensure maximum recovery from it's offshore areas. But the country stands as the most critical area in the current price climate. Decommissioning will ramp up in the near term, but further collaboration among UK operators and an improved regulatory system could sustain its longer-term offshore market.