IRISH DRILLING-1: Study analyzes downtime of exploration wells

A recent engineering study of downtime analysis of all exploration wells drilled to date in Ireland provides indicative drilling time-depth curves that can be used for estimating budgets for summer drilling in different sectors offshore Ireland.

The study was commissioned by Ireland’s Petroleum Affairs Division (PAD), part of the Irish Department of Communications, Marine and Natural Resources. In 1997, PAD set up the Irish Petroleum Infrastructure Program to promote hydrocarbon exploration and development activities in Ireland.

Downtime analysis produces recommendations to improve drilling performance offshore Ireland. The first part of this series includes discussion of basins off the eastern, southern, and northwestern coasts of Ireland: Central Irish Sea; Kish Bank; Celtic Sea; Fastnet basin; Donegal, Erris, and Slyne basins. The far western and southwestern basins, including the Porcupine basin, Goban Spur, and Rockall basin, will be covered in the conclusion next week.

None of the Irish Shelf drilling areas presents serious hole problems. Where overpressure was encountered, it did not result in significant downtime. Through lessons learned there has been a definite improvement in drilling performance achieved over the years. Furthermore, Ireland is not a particularly remote or costly location for drilling when compared with North Sea operations.

Drilling operations

Exploratory drilling in Irish waters started in 1970. Of the 154 wells drilled by mobile drilling units (151 unique wells plus 3 planned sidetracks), 80 are in the North Celtic Sea. An additional 14 platform production wells were drilled on the Kinsale Head gas field. In the late 1970s and early 1980s there was significant drilling activity in the Porcupine basin where a total of 30 wells plus 1 planned sidetrack have been drilled since 1979.

Elsewhere, activity has been somewhat intermittent, with some notable activity in and around the Corrib gas field in the Slyne basin.

Drilling offshore Ireland has tailed off since reaching a peak of 15 wells spudded in 1978. Appraisal and development of several small gas fields in the vicinity of Kinsale Head gas field resulted in increased activity in recent years.

But outside the North Celtic Sea, exploration has been quite limited given the large prospective acreage. This is despite encouraging finds such as the Connemara field in the Porcupine basin and Corrib gas field in the Slyne basin.

Downtime analysis

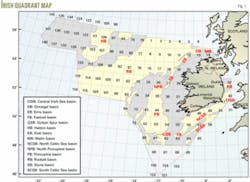

The wells were grouped for analysis into five geographical areas that had similar metocean and subsurface conditions (Fig. 1).

The first three geographical areas are discussed in this article; the last two areas will be published in the concluding part.

Central Irish Sea, Kish Bank

These basins lie off the east coast of Ireland in relatively shallow water, typically 20-80 m. Although bad weather can cause operational delays, there is shelter from the worst of the Atlantic weather.

Jack ups and semisubmersible drilling rigs have been used for past drilling. Potential reservoir in both basins is Triassic or older in age. This area has had the fewest wells drilled in the past and there has been no activity for more than 6 years.

North, South Celtic Sea, Fastnet

Off the south coast of Ireland, wells have been drilled in the Celtic Sea and Fastnet basin in water depths between 75 and 135 m.

Floating rigs have been used exclusively. Moored drillships were used in the earlier wells with standard moored semisubmersibles predominantly used from the mid-1970s.

Although the North Celtic Sea is relatively close to the Irish coast, it is exposed to the prevailing southwesterly winds, and weather can be extreme, especially in winter. The South Celtic Sea and Fastnet basins are further offshore and subject to similar weather conditions.

Potential reservoir formations are generally of Cretaceous, Jurassic, or Triassic age. Cretaceous chalk is often found very close to seabed, particularly in the North Celtic Sea. It is in this area that Ireland’s only producing gas fields are situated, and in which by far the most wells have been drilled.

Erris, Slyne, Donegal

These basins lie off the northwest coast of Ireland and, while they are much closer to shore than the Rockall basin, there is no shelter from the prevailing Atlantic weather systems. Water depth varies from just more than 100 m to around 400 m.

Geologically the regions also vary. Top hole drilling is often difficult due to shallow Tertiary volcanics, and drilling progress can be very slow whenever the Jurassic Broadford Beds formation is present. Potential reservoir is Triassic (Corrib field) or possibly Jurassic.

The Slyne basin has seen some recent activity primarily on the Corrib gas field. Erris and Donegal basins have seen little activity, although there was one very recent exploration well drilled on Erris.

Porcupine; Goban Spur

These are the deepwater drilling regions off the southwest coast of Ireland in the Atlantic Ocean. Wells have been drilled in water depths from 250 m in the shallowest parts of the northern Porcupine basin up to a maximum water depth of nearly 1,000 m in the Goban Spur basin. Moored and dynamically positioned drillships and semisubmersibles have been used in this area.

Geologically, the deepwater regions west of Ireland tend to have a greater thickness of Recent and Tertiary sediments than elsewhere off Ireland, and wells are generally drilled to greater total depths. Potential reservoir formations are Tertiary, Cretaceous, or Jurassic (Connemara field).

The Porcupine basin is second to the Celtic Sea in terms of total wells drilled, although activity has dropped in recent years. There has been only one well drilled in the Goban Spur basin. This area will be discussed in the concluding part of this article.

Rockall basin

This is the ultradeepwater region to the west and northwest of Ireland in the Atlantic Ocean beyond the Erris, Slyne, and Donegal basins. The maximum water depth drilled in Irish waters to date was 1,623 m in the Rockall basin. The number of wells drilled in the Irish sector of the Rockall basin is small (two wells plus one sidetrack), and therefore three wells from an adjacent part of the UK sector were included in the analysis of drilling downtime, which will be discussed in the next issue.

Methodology

The well histories and mud logging data for each of the 154 wells, mostly provided by PAD was reviewed and key data for each well recorded on a spreadsheet. Each spreadsheet contains:

• Key well statistics.

• Estimated timings for various well phases.

• Estimated downtime under various categories.

• Data to allow simple drilling efficiency measure.

• Comments on downtime and general well design and performance.

This information was then tabulated for all wells within each of the geographical areas and charts produced in order to:

• Determine most significant areas for drilling downtime.

• Identify if improvements have been made over the 30 years since the start of drilling off Ireland.

• Establish some very general duration vs. depth curves for each area.

Table 1 gives a summary of the engineering downtime breakdown for all of the five areas.

Central Irish Sea, Kish Bank

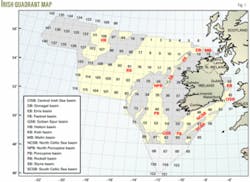

Fig. 2 shows a summary of the drilling times in the Central Irish Sea (CIS) and Kish Bank. Due to the clear change in performance since 1990, the data have been plotted separately for pre and post-1990 wells, with trend lines fitted to both data sets.

The green trend line could be used as a reference for estimating budget times to drill wells in the CIS and Kish Bank from spud to TD. Durations are very similar to the average times being achieved on vertical wells drilled from jack up rigs in the Morecombe Bay area and wells drilled from semisubmersibles in relatively shallow water in areas such as the Moray Firth.

The significant improvements made over pre-1990 wells are due to a combination of slimmed down well design, elimination of intermediate logging through use of LWD and superior bit performance.

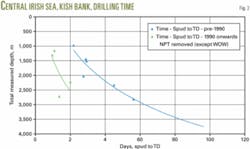

Fig. 3 shows the drilling downtime breakdown.

An analysis of downtime information produced the following conclusions:

• Weather conditions in the Central Irish Sea and Kish Bank, while less severe than the Celtic Sea and Atlantic Ocean, remain an important factor in overall well cost.

• Winter drilling is feasible at the expense of increased potential for weather related downtime.

• Water depths in the area range from too shallow for a semisubmersible to too deep for a standard jack up. Water depths over much of the area are suitable for both types of drilling unit.

• Rig selection will depend on water depth, timing, availability, day rates, and cost of mobilization and demobilization.

• The greatest single source of downtime has been associated with top-hole drilling. It is this area that would merit the most planning attention for any future wells to be drilled, particularly in Blocks 41 and 42.

• Beneath the troublesome shallow sediments, formations are competent and generally stable. There is no evidence of any significant overpressure.

• Vertical wells can be drilled with water-based mud without problems.

• Strong currents need to be considered in selection of equipment (ROV, surface casing, etc).

• Significant improvements in drilling performance have been made. One bit/hole section is a realistic objective.

Celtic Sea, Fastnet basins

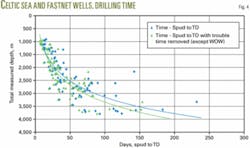

Fig. 4 shows the drilling times in the North and South Celtic Sea basins and the Fastnet basin. The durations include all flat spots (casing and BOP installation, intermediate logging, etc.) together with all nonproductive time.

Unlike the other four Irish offshore drilling areas, there has been no clear step-change in drilling performance over the years in the North and South Celtic Sea and Fastnet basins. There have been definite improvements in drilling performance in terms of bits and well designs, but the benefits in the very shallow wells are not as marked as has been seen in other areas.

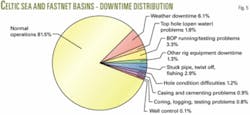

Fig. 5 shows a breakdown of drilling downtime. An analysis of downtime information led to the following conclusions:

• Weather conditions in the Celtic Sea and Fastnet basins are severe, particularly in winter. Historically, weather has been the greatest source of downtime in this area.

• Seasonal drilling has become the norm. Winter drilling is feasible but will greatly increase the likelihood of severe disruption to operations.

• All recent wells in the area have been drilled with standard semisubmersibles.

• The water depth is such that heavy duty jack-up rigs could operate, although the cost of this type of rig and mobilization issues would make it uneconomic for single well drilling.

• Top-hole drilling can be a persistent problem in this area. Improvements could be made in equipment and techniques to improve efficiency of conductor installation.

• Wells targeting the Cretaceous reservoir formations can be drilled with very simple and low-cost casing design.

• The shallow depth and ability to drill with minimal casing strings permit the installation of very efficient production well completions with horizontal tree technology.

• A number of subsea development wells has now been successfully completed in the Celtic Sea. The greatest cost savings for such wells will come from improving reliability of the completion equipment and eliminating downtime.

• Cretaceous formations in the area are generally stable, normally pressured, and apart from some hard surface drilling conditions, they do not present major difficulties.

• Once drilling reaches into the Jurassic, shale stability can become a problem and overpressure can occur, especially in deeper wells in this area.

Donegal, Erris, Slyne basins

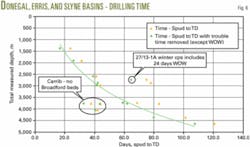

Fig. 6 shows drilling times in the Donegal, Erris, and Slyne basins; the data points show a very interesting correlation.

There is a cluster of three wells, which were drilled significantly faster than the others-these were three Corrib appraisal wells in which Broadford Beds were either not present or very thin. The other well lying off the trend is the 27/13-1A, which was drilled in winter and therefore has a disproportionately large element of weather downtime included.

Disregarding these four wells, a very good curve fit has been achieved as shown by the green line, which could be used as a reference for estimating budget wells times for summer drilling in the area.

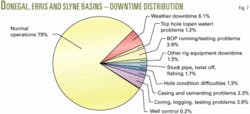

Fig. 7 shows the drilling downtime breakdown for the three basins. An analysis of downtime information led to the following conclusions:

• Weather conditions are a major factor in overall cost of the drilling operation. Weather has been the greatest single source of downtime in the Donegal, Erris, and Slyne basin areas.

• Winter drilling is unlikely to be economic given the likelihood of prolonged downtime.

• Winter weather conditions may exceed the design criteria for some rigs.

• Many standard semisubmersible rigs are suitable for summer operations in this area.

• Close attention must be paid to BOP and mooring equipment specifications and operational history.

• Well design must take into account the shallow sediments, in particular the presence of basalt near seabed.

• Geology plays a critical role in drilling performance in this area. Where thick Jurassic Broadford Beds formation is present, overall well duration is likely to be significantly increased. The Triassic Sherwood sandstone reservoir can also prove difficult to drill.

• PDC bits are widely applicable, although to date have been unsuccessful in Broadford Beds or Sherwood sandstone. Further advances in PDC cutter design could provide a significant breakthrough in drilling performance.

• Well testing in moderately deep water can be problematic. Lessons learned from the hydraulic fracture job carried out on the Corrib field could be useful for future wells.

• Within this area, based on previous wells, there is a risk of encountering minor overpressure, which could result in a well control incident. Past well control incidents have been handled relatively easily. ✦

The author

Nick O’Neill ([email protected]) is a director and project manager at CSA Group Ltd., Dublin. He has also worked in the Middle East as a drilling engineer and base manager with Geoservices SA. Before joining CSA in 1994, O’Neill worked as an independent consultant in operations geology. He holds a degree in geology from Trinity College Dublin (1977) and an MSc in petroleum geology from University College Dublin (1987). O’Neill is a board member of the Institute of Geologists of Ireland and a member of the American Association of Petroleum Geologists and the Energy Institute.