Horizontal wells find varied applications in Saudi fields

M.S. Al-Blehed, G.M. Hamada, M.N.J. Al-Awad, M.A. Al-Saddique

King Saud University,

Riyadh

Horizontal-well applications in Saudi Arabia have many objectives, such as controlling oil and gas coning in relatively thin remaining oil columns, improving waterflood sweep efficiency, improving productivity rates from thin and tight reservoirs, and saving development costs.

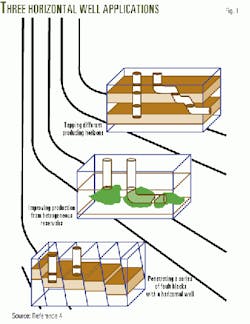

At yearend 1999, about 200 horizontal wells had been drilled in Saudi oil fields.

Horizontal wells

Horizontal wells are recognized as one of the most important technical advances in the oil and gas industry in the last 20 years.

At first, the industry considered this technology to be an exotic way of drilling, and reservoir and production engineers were skeptical of its economical feasibility. But industry has produced a variety of new techniques for horizontal drilling that have made this technology applicable in many cases.

The downhole turbodrill and bent-sub combination for direction drilling was a major breakthrough in horizontal drilling. Other advances include advancements in directional steering tools, new tools such as resistivity at bit (RAB), and measurement while drilling (MWD) tools.1 2 These advances have allowed the industry to drill horizontal laterals greater than 29,000 ft.

From 1980 to 1984, only one or two horizontal wells were drilled annually worldwide, but by 1988 the number of horizontal wells had increased to over 200/year. Projections indicate that by yearend 2000 more than 5,000 wells/year will be drilled horizontally.

The productivity improvement of a horizontal well compared to a vertical well in the same reservoir is controlled by the horizontal section length, target layer thickness, and permeability heterogeneity.

In the Saudi Arabia-Kuwait Neutral Zone, a 2,000-ft horizontal well completed in the upper layers of a 40-year-old depleted reservoir can produce, over 5 years, seven times more than a vertical well at the same location.

The potential of horizontal wells has been recognized throughout the Middle East. At yearend 1994, horizontal wells numbered more than 200 in Oman, 80 in Saudi Arabia, 50 in Abu Dhabi, 20 in Kuwait, and 6 in Egypt.3

Well applications

Horizontal wells should be considered for many exploration and development programs. The main goals of horizontal wells are to maximize ultimate recovery, maximize economics for recovering reserves, sustain a high production rate for as long as possible, and characterize and evaluate the reservoir.

Certainly not all reservoirs need horizontal wells, and some reservoirs could be developed with both vertical and horizontal wells. Increased production rates from horizontal wells can reduce the number of wells required for developing a field. For offshore fields, fewer wells reduce the number of platforms or other structures required.4-6

The industry primarily has restricted horizontal wells to production applications, but exploration can also benefit from horizontal drilling, not as the primary tool but as a secondary tool.

In other words, once conventional vertical drilling has proven the reservoir and structure, horizontal wells can improve the lateral knowledge to better-define the reservoir characteristics between vertical wells.

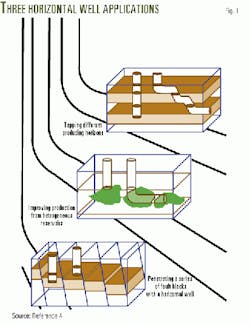

Horizontal wells can dramatically improve production by providing a greater contact of the reservoir to the wellbore. A horizontal well may also offer other advantages such as decreased pressure drops and fluid velocities around the wellbore, minimized water and gas coning, and accelerated production.

These wells can significantly increase production from several types of reservoirs, such as naturally fractured reservoirs, thin reservoirs, heterogeneous reservoirs, reservoirs under urban areas or offshore, vertical permeability homogeneous reservoirs, reefs or isolated sand bodies, and faulted reservoirs.

Fig. 1 shows three scenarios where horizontal wells can prove to be ideal.

In active waterflood and enhanced oil recovery (EOR) fields, horizontal wells can provide the following five advantages, as follows:

- Increase lateral sweep efficiency.

- Increase drainage and swept volume in severely faulted or heterogeneous reservoirs.

- Reduce heavy oil viscosity via efficient steam injection.

- Reduce heat loss during steam injection.

- Reduce the number of infill wells required for waterflood or EOR program.

Horizontal drilling has paved the concept of drainage architecture. Today, it is possible to drill many types of well geometries inside the reservoir and therefore to create various flow patterns.

The reservoir engineer must define the proper drainage architecture adapted to the fluids, the production mechanism, and the formation characteristics, while the drillers must implement the architecture economically.7

Saudi applications

Saudi Arabia contains the largest concentration of oil reserves in the world, including the world's largest onshore field, Ghawar, and the world's largest offshore field, Safaniya.

Saudi Arabia has more than 50 fields that contain a total of about 250 sandstone and carbonate reservoirs.8

Saudi Arabia's estimated remaining proven reserves are more than 257 billion bbl of oil, or about 25% of the world's proved reserves.

In Saudi Arabia, horizontal well technology has been applied to improve reservoir performance, to implement development projects cost effectively, and to explore for and recover hydrocarbons from difficult-to-produce oil and gas accumulations.

Fig. 2 shows the estimated horizontal wells drilled in the world and Saudi Arabia. In Saudi Arabia, horizontal wells have been used in both offshore and onshore fields to solve various problems.8-11

Offshore fields

Berri field is both onshore and offshore along the western edge of the Arabian Gulf. Its 1994 daily production rate was about 300,000 bo/d. Berri was the first field in Saudi Arabia to include horizontal wells. (The year 1994 is the latest for which full production data for Saudi Arabia are available.)

The carbonate reservoir has good hole stability and allows for openhole completions. The horizontal well completions have two or three times the producing rates of conventional wells because the horizontal wells increase exposure to the wellbore of thin oil columns or tight rock sections.

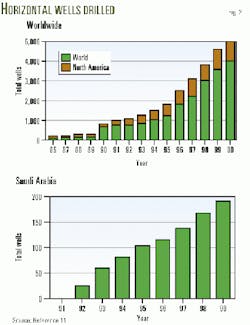

Fig. 3a shows a horizontal section of more than 1,500 ft, drilled along the top of the reservoir above the oil-water contact and away from the water cone. The well has since produced very little water.

Marjan field (Fig. 3b), 9 miles offshore in the Arabian Gulf, produced at rates of 400,000 bo/d in 1994.

The field consists of four main areas: Marjan, Lawhah, Maharah, and Hamur. These areas have 13 oil-bearing reservoirs. The Khafji reservoir is the only one on production.

The reservoir has a strong water drive and a large gas cap. The objective of the three horizontal wells drilled in this zone was to reduce gas and water coning and to double production rates, compared with conventional wells.

All three horizontal wells are in the Khafji thin stringer sands. These wells have shown that horizontal wells can be cost-effective for improving productivity in thin reservoirs.

Zuluf field, one of the northernmost fields in Saudi Arabia, is about 35 miles offshore in the Arabian Gulf. In 1994, it produced 500,000 bo/d. The field has eight oil and gas-bearing reservoirs.

Khafji, the main reservoir, has a strong water drive and gas cap. Three horizontal wells have been drilled in the Khafji main sand to control gas and water coning, and the productivity of these wells is four times that of nearby vertical wells.

Another three horizontal wells have been drilled to exploit thin sands in the Khafji (Fig. 3c). Production from these is more than twice that of offset vertical wells.

Safaniya, the world's largest offshore oil field, is divided into three areas: North, Central, and South. It has eight producing reservoirs and, in 1994, produced about 960,000 bo/d.

The main producing reservoirs are the Safaniya and Khafji. The objective of the horizontal wells in this field was to reduce water coning in areas with a thin oil column and to improve the mobility ratio (Fig. 3d).

Two horizontal wells are in the Khafji reservoir and four are in the Safaniya reservoir. These wells have outperformed conventional vertical wells by a factor of two.

Onshore fields

Ghawar, the largest producing field in the world, had a 1994 daily production of about 5 million bo/d. Ghawar has several producing reservoirs. All reservoirs are carbonates, and the main producing formation is the Arab-D sequence.

Most horizontal wells in the Ghawar field aim to increase waterflood efficiency by improving sweep efficiency and injection performance. The drilling of horizontal producing wells has just begun. Fig. 3e shows a horizontal well at the top of Arab-D sand reservoir in an area with a thin oil column.

Water injection wells have enabled Ghawar producing wells to continue to flow without the need for artificial lift.

Abqaiq, the most mature oil field in Saudi Arabia, was discovered in 1940. Production began in 1946 and in 1994 it produced about 650,000 bo/d. Abqaiq contains four producing bearing sequences.

Arab-D horizontal wells in areas with a thin oil column aim to increase waterflood efficiency and recover additional oil. Vertical wells in these areas produce with high water cuts and restricted rates to avoid water coning. Horizontal wells, on the other hand, can be produced at greater rates.

Fig. 3f shows a horizontal well traversing different producing layers of the Abqaiq field's Hanifa reservoir.

Horizontal well benefits

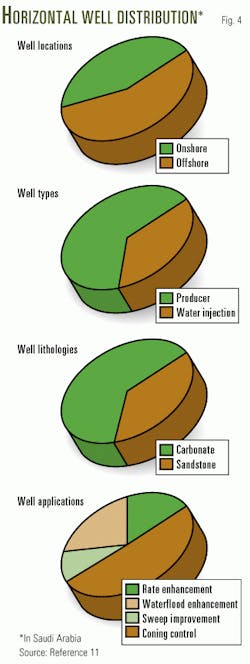

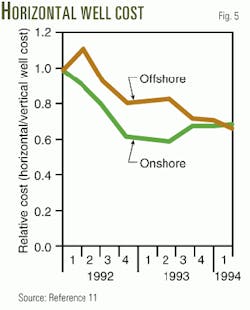

Figs. 4 and 5 illustrate the drilling cost and the distribution of the Saudi horizontal wells according to the type of field, nature of the well, lithofacies of the producing zones, and reason for drilling the horizontal well.

Horizontal wells in Saudi oil fields have yielded the following benefits:

- Improved well production capacity by 150-400%.

- Reduced the number of wells needed by 30%.

- Reduced water and gas handling costs by up to 50%.

- Reduced drilling, flowline, and facilities cost by 20-25%.

- Controlled well and reservoir performance problems.

Saudi Aramco is committed to horizontal well technology because of its cost-effectiveness and its ability to enhance reservoir performance.

The relative cost curve of a horizontal well to a vertical well is about one to one in offshore and offshore fields in the period 1992-1994 (Fig. 5).

References

- Ginnesini, J.F., "Horizontal Wells: An Overview," OAPEC-IFP Workshop on Horizontal Drilling and Application, Paris, June 23-25, 1992.

- Petit, H., and Lesage, G., "Adapted Screening Procedure, Key to Successful Horizontal Well Engineering Projects," OAPEC-IFP Workshop on Horizontal Drilling and Application, Paris, June 23-25, 1992.

- "Horizontal Well Technology," Horizontal Well Technology Seminar, Schlumberger Oil Services, Cairo, Feb. 10-12, 1991.

- Hamada, G.M., "Horizontal well Technology in Egypt," EGPC Seminar on Horizontal Well Technology, Cairo, July 26, 1996.

- Hamada, G.M., and Al-Blehed, M.S., "Emerged Horizontal Drilling Technology and Its Applications in Saudi Oil Fields in the Last Ten Years," Paper SPE No. 57322, Asia Pacific Conference, Kuala Lampur, Malaysia, Oct. 25-26, 1999.

- Renard, G., and Sabathier, J.C., "Integration of Horizontal Drilling into Reservoir Management Practice," OAPEC-IFP Workshop on Horizontal Well Drilling and Application, Paris, June 23-25, 1992.

- Legros, E., "A Technical Success for Elf Aquitaine: Horizontal Drilling," Intl.Petrol. Gaz, Chim, April 1983, pp. 56-59.

- El-Malik, M., "Notes on Petroleum Engineering," King Saud University, 1998

- Al- Buraik, K.A., "Application of Long Radius Horizontal Drilling Technology in Saudi Arabia; a Case History," OAPEC-IFP Workshop on Horizontal Well Drilling and Application, Paris, June 23-25, 1992.

- Ogawa, N., and Minh C.C., "Log Interpretation and Partial Solutions in Horizontal Wells Drilled Offshore-Neutral Zone," Paper No. SPE37775, 10th MEOS, Bahrain, Mar. 15-18 1997.

- "Horizontal Drilling in Saudi Arabia," Saudi Aramco, Summer 1995.

The authors-

Mohamed S. Al-Blehed is an associate professor at King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. His interests are petroleum economics, energy modeling, and reservoir evaluation. Al-Blehed holds a BS in petroleum engineering from Riyadh University and an MS and a PhD in petroleum engineering from the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

Gharib M. Hamada is a professor of well logging and applied geophysics at Cairo University, Egypt. He is currently with King Saud University. Previously, he was with the Technical University of Denmark, and Sultan Qaboos University, Oman. Hamada holds a BS and an MS in petroleum engineering from Cairo University and a DEA and a DIng in applied geophysics from Bordeaux University, France.

Musaed N.J. Al-Awad is an associate professor at King Saud Unversity, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. His interests are drilling engineering and petroleum-related rock mechanics. Al-Awad holds a BS and an MS in petroleum engineering from King Saud University and a PhD from Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh.

Mohammed A. Al-Saddique is assistant professor in the petroleum engineering department of King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. His research interests include reservoir characterization, well testing, and reservoir performance. Al-Saddique holds a PhD in petroleum engineering from Texas A&M University, College Station.