Energy reform could unlock Mexico's shale resource potential

Rachael Seeley, Editor

The oil and gas industry is watching with great interest as energy reforms unfold in Mexico. The country has taken the first steps toward opening its energy industry to outside investment that could unlock the potential of its massive unconventional resource. Constitutional reforms, enacted in December, ease investment restrictions and tax obligations for state oil company Pemex and open a path for investment from outside the country for the first time in 75 years.

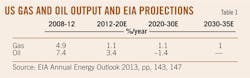

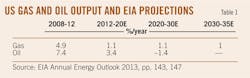

Mexico holds a sizable unconventional resource base. With an estimated 545 tcf of technically recoverable shale resources, the country ranks sixth in the world in terms of shale gas potential, behind China, Argentina, Algeria, the US, and Canada (Table 1).

The country ranks eighth in the world in terms of oil and condensate technically recoverable from shale, estimated at 13.1 billion bbl by the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) in January 2014 (Table 2).

The greatest known shale potential exists in the portion of the Eagle Ford shale that extends into Mexico's Burgos basin from South Texas.

"Oil and gas-prone windows extending south from Texas into northern Mexico have an estimated 343 tcf and 6.3 billion bbl of risked, technically recoverable shale gas and shale resource potential," EIA said.

Pemex—which has for decades held a constitutional monopoly on development of Mexico's oil and gas reserves—is the only company that has tested the Eagle Ford in the Burgos basin. Pemex has drilled four exploratory wells and released initial production data for two of these.

The first well, the Emergente-1, was drilled in late 2010 a few miles south of the Texas-Coahuila border along a continuation of the Eagle Ford trend from South Texas.

The initial horizontal well, drilled in the dry-gas window of the formation, reached a true vertical depth of about 8,200 ft with an 8,366-ft lateral. Pemex completed it using a 17-stage fracture stimulation treatment. It tested at a modest initial production rate of 2.8 MMcfd of gas. EIA estimates the well cost $20-25 million to drill and is uneconomic at current gas prices.

Results were also released for Pemex's Habano-1 in the Eagle Ford's wet gas window. The well had an nitial production rate of 2.771 MMcfd of gas and 27 b/d of crude. Initial production rates are not available for the Nomada-1 well drilled in the oil window or the Montanes-1 well drilled in the wet gas window. Pemex plans to drill up to 75 shale exploration wells in the Burgos basin through 2015.

A fifth Eagle Ford shale exploratory well, the Percutor-1, tested the formation in the more geologically complex Sabinas basin to the southwest. That well, drilled in a dry gas area, had an initial production rate of 2.17 MMcfd.

Reforming exploration

One of the biggest hurdles to developing Mexico's unconventional resources was removed in December 2013 when Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto signed a landmark energy bill that encompassed several key constitutional changes—including the removal of a prohibition against private investment in the oil and gas industry.

The reforms are the most dramatic made in the Mexican oil and gas industry since its nationalization in 1938.

Benjamin Torres-Barron, a partner in the Mexican offices of law firm Baker & McKenzie, called the reforms a true game changer. "No one ever really believed that it was ever going to happen. We've been aiming for this for decades and throughout several federal government administrations."

Now that the constitutional reform has passed, work has begun on a legal framework for oil and gas development and draft contract models for private investment. Many lingering questions will be answered when Congress finalizes the secondary legislation, due for release by Apr. 19.

Contract preparation

Torres-Barron recommends that exploration and production companies interested in investing in Mexican oil and gas begin preparing now for the first state contract tenders, likely in 2015.

Bidding will occur soon after the first tender. Torres-Barron said doing early research will give companies an advantage. "Once the tender is launched you have a very narrow timeframe to incorporate a Mexican entity, to understand the rules, to have them translated for the language barrier, and to analyze the tax structure," Torres-Barron told UOGR at an industry conference, hosted by Baker & McKenzie, in Houston.

He recommends companies begin researching now—analyzing the fields likely to be offered, getting a sense of the competition, and becoming familiar with local authorities. It would also be prudent, he said, to begin building relationships with local contractors. This will help operators take advantage of opportunities when they arise.

"Do your homework," Torres-Barron said. "First you need to know the rules of the game. You will need a group of advisors who will help you."

Before tenders are announced, Torres-Barron recommends assembling a local team of legal and tax advisors familiar with Mexico's regulatory framework and tax structure, as well as advisors from abroad familiar with the contract models likely to be introduced. Companies that can understand the terms of contract tenders before they are announced will have an advantage, he said.

New contract models for exploration and production companies could include a combination of profit-sharing or production-sharing agreements with Pemex or the federal government, license agreements with the federal government, and service agreements with Pemex involving only cash payments.

Pemex's challenge

The reforms also call for reducing the tax burden on Pemex and restructuring the company. Pemex will soon have the ability to enter into partnerships with private parties that could aid in providing the expertise, equipment, and capital needed to explore and develop the country's shale resources, as well as other areas of high resource potential—such as deepwater.

Reform was underpinned by Pemex's declining production numbers. The company is a key part of Mexico's economy, with oil revenues accounting for 8.6% of gross domestic product, and tax revenues covering roughly 30% of the federal government's expenses in 2013, according to analysis by Barclays.

The bulk of Pemex's production comes from legacy oil and gas fields that are in decline, and the company's ability to invest in new production has been hampered by high taxes. Michael Cohen, an analyst with Barclays, said Pemex paid roughly 65% of its revenues in taxes in 2012. "Tax obligations have almost eliminated Pemex's net income, making it very difficult for the company to replace reserves fully over the past 3 years," Cohen said. The company posted a reserves replacement rate of 96% in 2012.

Torres-Barron, of law firm Baker & McKenzie, said Pemex was subject to a variable income tax rate that could reach 70%.

Limited investment by Pemex has hurt production. Crude oil output declined by 1 million b/d over 10 years, Enrique Ochoa Reza, the Mexican energy ministry's undersecretary of hydrocarbons, told a Dec. 19 discussion at the Atlantic Council. The International Energy Agency estimates the country produced 2.5 million b/d in November 2013.

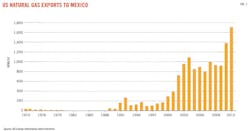

Natural gas production has also slipped. Analysis by Barclays shows that Pemex's gas production averaged 5.6 bcfd in July 2013, down from a peak of 6.5 bcfd in January 2010, resulting in a growing reliance on imported gas. Natural gas imports climbed to meet 30% percent of demand in 2012 from 3% in 1997.

EIA reports that Mexico imported a record 2.1 bcfd of natural gas in 2012, up 21% from 2011. Eighty percent of gas imports came via pipeline from the US (Figs. 1-2).

Torres-Barron told UOGR, "Pemex and the federal government realized they could not sustain current production levels to meet the country's demand."

Mexico has taken the first steps toward revolutionizing its oil and gas industry, but unlocking its vast resource potential is bound to take time and requires more legislative pieces to fall into place.

Cohen said secondary laws need to be enacted in the first half of 2014, and an implementation process should occur throughout the second half of 2014 extending into 2015.

"The first contracts could materialize by then (2015), and the first flows of investment could be seen in 2016," Cohen said.

MEXICO REFORM: CONTRACT MODELSNew contract models for E&P activities include:

Source: Baker & McKenzie |