Refinery upgrades essential to Russian recovery

Properly upgrading Russian refineries and eliminating damaging myths are keys to turning around the Russian refining industry and economy.

Western technical advice focuses on large project construction and ignores the enormous gains that can be achieved quickly and cheaply on smaller projects. Several myths about the Russian industry, propagated by both Westerners and Russians, have prevented an understanding of the industry needs and have blocked progress.

Dispelling these myths is necessary to develop a profitable, functional fuel sector:

- Myth 1. Many refineries should be shutdown because there is too much refining capacity.

- Myth 2. Reconstructing or closing each Russian refinery will cost hundreds of millions, if not billions of dollars, and this money does not exist.

- Myth 3. Ruble devaluation has made the Russian fuel industry (and the economy as a whole) more competitive.

The undertaking of smaller projects compared to most of those undertaken today represents Russia's best hope for recovery. These projects will provide a cheaper and more balanced fuel supply.

Such projects should be a priority for both the Russian government and major Russian oil companies. Western credit agencies, banks, and engineering companies can assist this process by exercising better judgment and more flexibility in choosing which projects and companies to finance.

The problem

Russian oil refineries were built to satisfy the demands of Soviet industry: large volumes of fuel oil, low-quality diesel, and low-octane gasoline. They no longer produce what the market requires, an increasingly acute problem as Russian product demand is undergoing a fundamental and permanent transformation.

The refineries' equipment and processes are often outdated and inefficient. Additionally encumbered with disproportionate tax, payroll, social burdens, and often incompetent or corrupt management, Russian refineries find themselves on the very edge of survival. Equally threatened are the regional budgets, labor force, industry, and agriculture that heavily depend on them.

Two factors exacerbate the problem: Refineries process too much crude and they produce the wrong products. Since export pipeline capacity limits crude exports to about 40% of production, the rest must be domestically refined.

This excess crude goes to refineries with a severe lack of conversion capacity. Many Russian refineries exhaust their hydrotreating and reforming capacities when the crude unit is at 40% of capacity. Other refineries have limited or no conversion facilities.

Russian refineries inadvertently provide a multibillion dollar subsidy to Western economies because they can't extract light fractions from the crude. They export 25 million tonnes/year (tpy) of low-value fuel oil to the West, where the fractions are extracted and used. Instead of fuel oil, these products could be high-value diesel or gasoline exports.

Lack of secondary processing capacity limits the average gasoline yield to 16% or less. To meet total Russian gasoline demand of 24 tpy, refineries need to process a minimum of 160 million tonnes. The resulting surplus of low-value products will be about 30 million tonnes of fuel oil.

Worse yet, as nearly all the naphtha fraction is required for gasoline production, the Russian petrochemical industry is starved of a primary feedstock.

Myth 1

According to Myth 1, there is too much refining capacity, and therefore, many refineries need to be shut down. Although there is too much refining capacity in Russia, the focus on shutdowns should be on inefficient refining units, not on entire refineries.

Total primary refining capacity is 300 million tpy, and the country requires only 100 million tpy of products.

The proposed solution to close refineries to reduce capacity is neither totally wise nor realistic. Most Russian refineries were built over many years. Therefore, they possess both very old and quite modern units. A refinery typically has three to five primary atmospheric-vacuum distillation units (AVTs).

Fully closing a refinery means loss of both old and modern units. As a result, the overall efficiency of the industry would not increase and might even decrease.

The solution to overcapacity is not the closure of complete refineries. Rather, the oldest and least efficient units in each refinery should be closed, primarily the AVTs. Newer, more efficient units should be operated at close to full capacity.

Bringing the distillation capacity in closer balance with the secondary processing capacity will substantially increase efficiency and result in a higher degree of conversion.

The problem is exacerbated by both Russian and Western specialists who focus on hypothetical economies of scale. They tout that increased crude runs means decreased cost per barrel of product.

How can it be logical, however, for a Russian refinery to run full-throttle to capture a 10% average cost reduction when it can't even profitably sell the last 40-50% of production? Yet much emphasis has been placed on achieving virtual economies of scale rather than real economic value.

In addition to persuasive economics, down-scaling refineries is the only realistic political and social option. In many towns, refineries provide the major source of employment and revenue. Fully closing such refineries would be destabilizing and entail unacceptable social and environmental costs for the next 10-15 years.

Myth 2

Many believe that reconstructing or closing each Russian refinery will cost hundreds of millions of dollars. On the contrary, several quick and cheap upgrade projects can increase refining productivity.

The actual sums required for refinery upgrades have been exaggerated on all sides.

Western engineering companies are seeking billion-dollar supply contracts, and Russian refinery management is seeking gold-plated (but suboptimal) projects on credit. Also, Western export credit agencies are trying to maximize export volumes.

The result has been a distorted focus on building new, expensive Western units, not on cost-effective reconstruction of existing ones. Russian management has been compliant on this point; after all, why should it bother to fix its old refinery when someone is offering to finance a new one?

Egos and corruption on the part of refinery management also heavily influence project choices. Signing a $500-million agreement provides more publicity and potential kickbacks than a $50-million deal.

The resulting plans are usually a hodgepodge of questionable projects that, if ever completed, would saddle Russian refineries with large additional foreign debt. In a country struggling to meet foreign debt obligations, this is disastrous for all sides.

This pressure has unfortunately obscured one fact: Huge gains in refining productivity can be achieved cheaply and quickly through minor upgrade projects.

Such upgrades create, in turn, a competitive, value-adding refinery that can self-finance all future projects with little or no debt burden. Additionally, such a refinery can pay its workers' salaries and taxes and play a key role in revitalizing Russian industry and agriculture.

Three Samara refineries fit the profile of plants with potential for minor upgrades that positively impact profit:

- The Samara refinery.

- The Novokuibishev refinery.

- The Syzran refinery.

The Samara region is a major Russian industrial center for oil production and refining, aerospace, machine building, metal working, chemicals and petrochemicals, agriculture, and food processing.

Although much of the economy is depressed, the progressive and vigorous efforts of the region's governor, Konstantin Titov, are making the region increasingly attractive to both Russian and foreign investors.

The region has 3.3 million inhabitants. Yet it is home to three oil refineries with a total primary distillation capacity exceeding 28 million tpy. Attempts by refinery management to deal with this huge overcapacity have yielded few results. Attempts have varied from pursuing the wrong projects to doing nothing at all. High fuel prices have also caused the region's economic recovery to suffer.

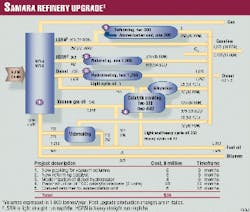

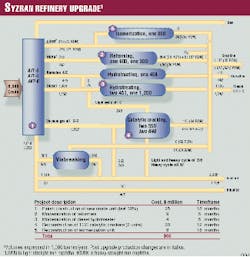

But this does not have to be the case. Figs. 1, 2, and 3 illustrate a plan to upgrade the Samara refineries to make the region a leading economic powerhouse by providing low-cost fuel and electricity to regional industries and agriculture.

In the Samara refinery, a $38 million upgrade over 18 months will increase gasoline and diesel production by 25% (Fig. 1). Project upgrades include new packing for vacuum columns, new reforming catalyst, modernization of a diesel hydrotreater, reconstruction of two catalytic crackers, and conversion of a reforming unit to an isomerization unit.

For the Novokuibishev refinery, Fig. 2 shows that $146 million in 24 months will bring about a 54% increase in gasoline and diesel production and an almost seven-times decrease in fuel oil production. If timing and money are more limited, a mere $36 million in 12 months will bring about a 27% increase in gasoline and diesel production.

In the Syzran refinery, a $66 million upgrade in 18 months will increase gasoline, kerosine, and diesel production by 30%. The suggested upgrade consists of completion of new AVTs, modernization of two reformers and a diesel hydrotreater, and reconstruction of two catalytic crackers and an isomerization unit.

If all three projects are implemented, gasoline and diesel production will increase by 48% and fuel oil production will decrease by 43%. This creates additional annual value of $450 million (Table 1).

The plans increase the tax base for Samara and provide new jobs. Provision of low-cost feedstock will also facilitate the recovery of the local petrochemical industry.

Samara refineries are uniquely positioned to become among the most efficient in Russia and dominate the Volga and Central Russian fuel markets.

For example, in comparison to Samara's needed upgrades, Tyumen Oil Co.'s Ryazan refinery upgrade will cost $285 million and take 3 years just to achieve a 68% depth of refining.

Depth of refining, a term used primarily in Russia, is the sum of the products, less fuel oil, less refinery fuel, and less losses, expressed as a function of crude capacity. Each Samara refinery can achieve a 75% depth for between $35 and $70 million and within 18 months.

With little or no debt burden, a central location, and Russia's best refining economics, the Samara refineries could become a dominant force on the Russian fuel market.

When will the sleeping Samara giant awaken, however?

Myth 3

The belief that the ruble devaluation has made the Russian fuel industry more competitive is a dangerous delusion. While the ruble has been devalued, the price for gasoline in Russia is still higher than average world prices.

The real problem, which remains unsolved, is that Russian refineries produce the wrong products and do not add value to the market. The refineries export large volumes of low-value products across thousands of kilometers of rail at dollar-based tariffs into a competitive world market. They still pay port charges in dollars, finance large dollar debts, and import critical equipment in dollars.

Russia cannot sustain this game for long. Domestic inflation is taking prices back to predevaluation levels. Fuel shortages have appeared as oil companies export products to capture higher profits abroad. And recently enacted administrative controls and price-fixing will, as in Soviet times, only prolong the agony.

Refineries will continue to produce the wrong products. They will continue to export at a loss, passing on their inefficiencies (in higher prices) to already-insolvent domestic customers such as heating and power plants, heavy industry, and farms.

For example, despite a 300% devaluation of the ruble, the wholesale ex-works price for Russian A-92 gasoline (92 octane) in October 1999 exceeded $300/tonne, while world prices were around $250/tonne. At these price levels, is economic recovery or growth even possible?

Hard-pressed federal and local budgets will pretend to subsidize. With no real funds available, however, the government will levy new taxes right back on the energy complex, whose taxes already represent a staggering 40% of all budget revenues.

The heat and power plants, unable to raise residential tariffs, will increase the already-suffocating industrial rates. Combined with a collapsed banking system and a choking web of mutual debts, this is hardly a recipe for Russian economic revival.

Temporary relief comes from today's high world prices for crude oil and refined products. But if this window of opportunity is squandered and the Russian fuel sector does not make significant investment now, then the next downturn in oil prices will likely trigger another Russian crisis and devaluation with a far worse outcome.

Solution

This vicious circle of Russian crises can and must be broken. All the necessary resources already exist: available investment capital, rational, high-return refinery projects, and qualified Russian-Western project implementation teams. What is lacking is enlightened leadership willing to directly address the problem.

One possible approach is to develop a realistic model for long-term refining in Russia and make each refinery economically self-sufficient in the short term:

First, a realistic model for economically sustainable refining in Russia should be based on processing economics, transport costs, potential for reconstruction, and social factors for each region and refinery.

The big challenge is to identify the key economic and geographical factors that will determine the future of Russian refining and prepare for these changes. Although Russia cannot change its size or control world oil prices, it can use its productive assets much more efficiently.

A working group comprised of specialists from Ministry of Fuel & Energy, private refinery representatives, and Western experts with extensive experience in financing and implementing reconstruction at Russian refineries could execute this phase quickly and inexpensively.

Second, each refinery should be economically self-sufficient in the short term with inexpensive projects that sharply improve performance. Closure of old AVTs and modernizing the remaining AVTs with new trays and packing and heat transfer systems will improve performance.

Also, refiners should replace catalysts in naphtha reformers, catalytic crackers, and diesel hydrotreaters where economically justified. Conversion of spare reforming capacity to isomerization is ideal. Upgrading catalytic cracking capacity, if it can be done quickly and cheaply, is also desirable.

Maximum use of domestic engineering, technology, and equipment can reduce project costs by taking advantage of the ruble's devaluation.

Taking such steps will create reasonably efficient and profitable refineries that are capable of self-financing or securing outside financing. Outside financing allows for capital-intensive projects, such as new catalytic cracking and hydrocracking units, which are necessary for modern, efficient refineries.

In the longer term, market economics will influence which refineries get fully upgraded, maintained, or closed.

Financing, as always, will play a key role. Russian oil companies should use the current windfall from high world oil prices to upgrade their refineries immediately. Federal and local governments should offer tax incentives to stimulate real investment projects.

Role of the West

Western engineering companies and financing sources such as the World Bank, International Finance Corp., and various export-import banks, can play a key role in Russia's recovery by financing concrete programs in the refining sector. But to do so, they must change their approach.

These financing sources must stop promoting the projects based on a purely Western technical solution. They should provide more support to smaller, high-yield projects. By supporting small, profitable projects, lenders can help Russian refineries achieve gains with their own assets and avoid loading refiners with huge external debt.

The West should finance more Russian content as it is cost-effective, rather than force the use of costly Western analogues. Where concern exists regarding the quality and efficiencies of Russian organizations, experienced Western firms could be hired to supervise their work.

What must be eliminated are the typical Western "white elephant" projects.

By working together with Russian oil companies and regional governments to identify and finance key projects with a direct benefit to the Russian economy, the West could achieve far more than it ever did with aid to Russia.

The Authors

Steven L. Geiger is a director with Anglo Petroleum & Mining. Previously, he held senior management positions with oil companies Total, Mitsui, and Yukos. He has developed energy projects in the Russian region for over 10 years. Geiger holds a BS in Economics from M.I.T., Cambridge, Mass., and an MBA from the Wharton Business School, Philadelphia.

Timothy W. Bibbs is a director of Euro Technical Services Ltd., a consulting company which provides engineering services to the oil, gas, and petrochemical industries in the former Soviet Union. Prior to establishing this company, Bibbs worked for Bechtel and UOP. He has been involved in the oil industry for 20 years and has worked in the FSU for the past 10 years. Bibbs holds an honors degree in chemical engineering from Imperial College, London.