US refining flexibility sustains export opportunities, profitability

Steven F. Crower

SDR Ventures Inc.

Denver

A lower crude oil price environment has sparked concerns that projected reductions in US light, tight oil (LTO) production will lead to reduced profitability for US refiners as readily available supplies of low-cost feedstock and natural gas dwindle. Domestic LTO and associated gas production have served as stable cost-advantaged feed and energy sources in the last few years. But steady growth in refined product exports during the last decade, alongside substantial investments in downstream processing before the US light crude production boom, have left US refiners well-positioned to maintain near-term profitability.

Finished product exports

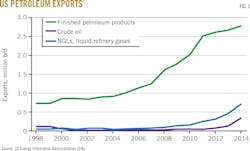

Incremental reductions in US demand for finished petroleum products (diesel, naphtha, and gasoline) amid growing global demand have prompted a trend of dramatically higher exports of finished products from US refineries.

The decline in US domestic demand for products was prompted by consumers seeking more fuel-efficient transportation, including ride-sharing and alternative-fueled vehicles, as gasoline prices followed crude prices higher starting in February 2009. US government data show, however, that US consumers have continued to use less finished product per capita despite recently lower pricing (Fig. 1).

With domestic demand for petroleum-based fuels projected to continue falling, US refining and midstream companies have made substantial investments to expand both processing capabilities and transportation infrastructure to meet broader global demand for refined products.

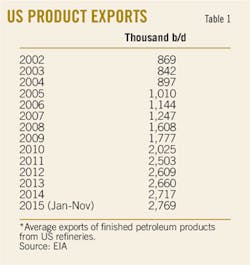

Since 2005, US finished product exports have increased 270% to more than 2.7 million b/d as of end-November 2015, marking the fourteenth consecutive year of increased product exports from US refineries to destinations abroad (Table 1).

Currently, about 50% of exports move to South America and Latin America, with Europe, Asia-Pacific, and Canada receiving about 13% each, according to statistics from the US Energy Information Administration (EIA).

Exports of US-sourced crude also are occurring, but account for only 2% of domestic daily production, according to EIA. The lifting of the 40-year ban on US crude oil exports in December 2015 likely will increase domestic crude export levels, but by how much, to which destinations, and how soon remain uncertainties.

Fig. 2 shows 1998-2014 trends in US exports of finished products, NGLs, liquid refinery gases, and crude oil.

Crude qualities, throughputs

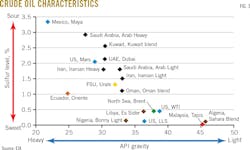

The value of a particular crude is based primarily on its American Petroleum Institute (API) gravity, or density, and its sulfur content. Because refineries price crude based on the next best available option, high-API, low-sulfur (light, sweet) crudes frequently are priced relative to low-API, high-sulfur (heavy, sour) grades. Any particular crude will be more or less valuable to a refiner based on that refiner's specific location, configuration, and ability to process varying types of crude quality.

US operators historically built and designed refineries based on proximity to regional crude supplies and demand for finished products. While ongoing consolidation and realignment efforts have contributed to a reduction in the total number refineries in the US to 121 from 161 in 1995 (OGJ, Dec. 7, 2015, p.24; Aug. 3, 2015, p. 58), a large portion of US refinery closures since the 1970s resulted from an inability to receive and process a variety of crude slates at reasonable costs.

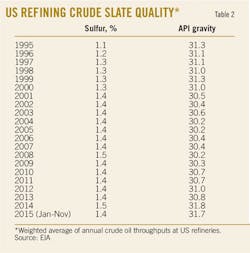

US shale development, however, has changed the domestic refining and energy transportation landscapes. While higher domestic LTO production has increased overall light crude throughputs at US refineries and encouraged future investments to accommodate projected increases in US LTO production,1 the overall average quality of processed crudes at US refineries since 1995 has remained relatively stable (Table 2).

Before the surge in domestic LTO production, declining output and rising costs of conventional light, sweet crude prompted many US refiners to invest billions of dollars in technology to process heavier, high-sulfur, and bitumen-based crudes from nearby producers such as Mexico, Venezuela, and Canada.

Between 1995 and 2015, US refiners added nearly 250,000 b/d of coking capacity, as well as more than 200,000 b/d in catalytic cracking and hydtrotreating combined (OGJ, Aug. 3, 2015, p. 58).

Even with consolidations and shutdowns in the refining space, overall US crude distillation capacity has risen to 18 million b/d from 15.0 million bpd in 1989, while the average refinery size has more than doubled to 130,000 b/d from 60,000 b/d in 1990 as domestic refiners have increased their ability to handle an array of crude qualities.

In addition to giving refineries the flexibility to process a wider variety of crudes, upgrades increased plant efficiency, reduced operating costs, and increased the ability to vary production slates in accord with seasonal and regional demand for finished products.

This combination of effects has made the US refining system uniquely qualified to profitably export refined products to meet rising global demand.

Fig. 3 shows the API gravity and sulfur content of selected domestic and imported crudes frequently processed by US refineries.

Transportation, pricing

Early indications from recent EIA weekly petroleum statistics suggest a downturn in late-2015 and early-2016 US product exports. Refiners that have access to low-cost transportation (rail, pipeline, or water) and are equipped to process a diverse crude slate likely, however, will continue profitable exports as global consumers once again adjust to cyclical dynamics typical of an oversupplied crude market.

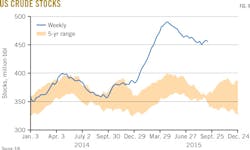

In 2010 as US shale production began to increase without adequate infrastructure to reach refineries, crude stocks started to build at WTI's Cushing, Okla., price point.

The US crude bottleneck allowed domestic refiners that had options to buy stranded US crude supplies to do so at deep discounts relative to WTI, prompting Brent-based crudes to trade up to a 28% premium above WTI (Fig. 4).

Lower WTI prices, however, did not immediately result in lower US gasoline prices because, as a globally priced and traded commodity, gasoline remained more closely tied to the international Brent marker (Fig. 5). US refiners were initially able to process increased volumes of discounted WTI-tied crudes to produce finished products that could fetch significant profits via export to global markets.

While investments in US crude-focused inland and port infrastructure (rail, storage, and pipelines) over the last 5 years have closed the price gap between WTI and Brent, they also have minimized bottlenecks and increased deliverability of LTO to refineries. These investments, combined with heightened operational flexibility, have increased refiners' ability to choose feedstock suppliers, both domestic and international, shielding them from interruption to domestic LTO production.

North American refineries have maintained considerably higher profitability than European refineries on an earnings/bbl-processed basis.

While many factors contribute to refinery profitability (power requirements, feedstock costs, access to high-value end markets, etc.), North American refiners' earnings/bbl processed tend to be higher than international competitors as a result of their greater ability to process a wide variety of crudes, according to an EIA analysis of 26 publicly traded companies based in North America and Europe.

Of these 26 companies, the 10 with nearly all refining capacity in North America consistently maintained higher earnings/bbl processed since 2011, beating their overseas-centered counterparts' by as much as $6/bbl in 2012 (Fig. 6).

Refiner to the world

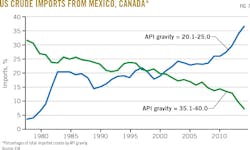

Imports of heavier, harder-to-process crudes from Canada, Venezuela, and Mexico, have gradually increased during the last decade and remain stable despite large drops in imported volumes of lighter, more expensive foreign grades.

As crude prices remain low and theoretically discourage further discretionary spending on capacity expansions or additions in countries exporting the heavy barrels to the US, this dynamic will continue to offer favorable returns to US refiners equipped to process these heavier grades into finished products for export back to these countries.

Heavy crude imports into the US from Canada and Mexico have steadily increased as both countries compete for capacity at US refineries (Fig. 7), even as it requires slashing prices to secure that capacity. At the same time, Mexico was the largest importer of US finished gasoline, according to EIA data, bringing in 287,000 b/d in November 2015. Its total products imports from the US were also the largest at 691,000 b/d. Canada was second at 609,000 b/d.2

State-owned Petróleos Mexicanos regularly has lowered the constant term, or K factor, included in monthly price formulas for Maya, Isthmus, and Olmeca crudes to decrease costs to the US in an effort to provide economic incentives for refineries there to displace Canadian crude feedstock with Mexican heavy options.

Light crude imports, however, have steadily dropped alongside rising US shale production. With heavy crude imports due to rise this year, light crude imports will continue to lag despite projections for average domestic oil production to fall to 8.9 million b/d from 9.32 million b/d in 2015 (OGJ, Jan. 4, 2016, p. 22) (Fig. 8). These foreign imports likely will continue to come from Canada, Saudi Arabia, Venezuela, Mexico, and Colombia, which were the top exporters to US refiners in 2015.

The combination of additional crude imports with ongoing domestic production should allow US refiners to continue to secure ample feed at reasonable costs for the foreseeable future.

Storage conundrum

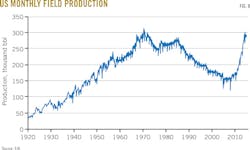

While an oversupplied crude market created sizeable profit margins for US refiners, crude storage capacity has not kept pace with increased US production (Fig. 9).

Projections indicate crude in domestic storage will drop in 2016, but only modestly, to 440 million bbl by yearend from 475 million bbl at the end of 2015. Crude in storage at Cushing has far exceeded its 5-year range despite several projects designed to alleviate system bottlenecks.

The 760-mile, 400,000-b/d Seaway pipeline which previously shipped oil north (to Cushing) from the US Gulf Coast was reversed in 2012 in an attempt to draw down excess inventories stranded at the WTI pricing hub. This reversal, however, only temporarily reduced storage problems. By 2014, Canadian crude imports to Cushing via the 600-mile, 600,000-b/d Flanagan South Pipeline from Chicago were pushing Cushing inventories to even higher levels (Fig. 10).

The timeframe for completion of additional debottlenecking remains uncertain in the current low-price environment. Should a temporary increase in US demand for finished products amid lower fuel prices sustain increased refining throughputs, debottlenecking projects likely will be executed more quickly.

References

1. LeRoy, Charles, "Refining US petroleum: A survey of US refinery use of growing US crude oil production," American Fuel & Petroleum Manufacturers, March 2015.

2. US EIA, "Petroleum and other liquids, Data, Exports by Destination," www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/pet_move_expc_a_EPP0_EEX_mbblpd_m.htm, accessed Feb. 5, 2016.

The author

Steven Crower ([email protected]) is director of energy at SDR Ventures Inc., where he provides merger and acquisition advisory services to all sectors of the industry. He also serves as adjunct professor at the University of Colorado at Denver, where he teaches courses on global refining and terminalling. Crower holds a BS (1991) in civil engineering from the University of Michigan and an MBA (1997) in finance from Rice University, Houston.