Financial sanctions impact Russian oil, equipment export ban's effects limited

Daniel Fjaertoft

Sigra Group

Indra Overland

Norwegian Institute of International Affairs

Oslo

In reaction to Russia's involvement in the conflict in Ukraine, the European Union and the US have launched two-pronged sanctions against the Russian oil sector. The equipment export ban will have limited effect during the next 10 years because it targets shale, deep water, and the Arctic, and few such projects are planned to come on stream before 2025. But the effect of financial sanctions is immediate and significant.

This conclusion stems from modeling Russia's oil production outlook in three scenarios. These encompass a range of possibilities, from a 2.5% fall by 2018 followed by recovery on one end, to a more long-term decline leading to 7% lower production by 2025 on the other. These estimates are conservative and do not fully account for the impact of sanctions and lower oil prices on companies like Gazprom Neft and Lukoil. They also do not take into account possible side effects of the equipment ban, the blurred boundaries of which may cause it to affect projects outside the targeted environments.

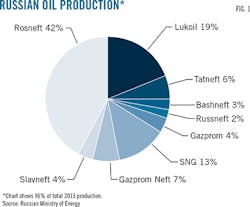

The expected fall in Russian oil output is linked to the decline in production from existing fields, the substantial investment needed to counter this decline, and the dominant role in the industry of state-controlled Rosneft. Rosneft produces more than 40% of Russian oil and its debt burden, in combination with sanctions-limited access to finance, make it unlikely that the company will be able to commit the resources necessary to maintain current production levels (Fig. 1).

The fall in oil prices aggravates the predicament of the Russian oil sector, but for Rosneft-which has low production costs, especially after the drop in the value of the ruble-sanctions are the main problem. Also other oil companies, among them Russia's largest private oil company Lukoil, are revising investment budgets, suggesting more new production is likely to be shelved.

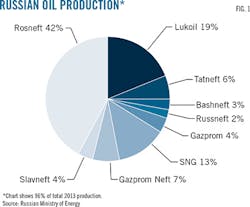

Russia is the world's second largest oil exporter, and developments in the Russian oil sector affect international markets, both for supplies and services and for the oil itself. The effect (or not) of sanctions (Table 1) is therefore significant for both Russia and the global petroleum sector.

Production

Exports of oil and gas make up around two thirds of Russian export income and half of Russian government revenue. In attempting to put pressure on the Russian state, sanctions therefore target the Russian state-controlled oil companies, Rosneft and Gazprom Neft in particular.

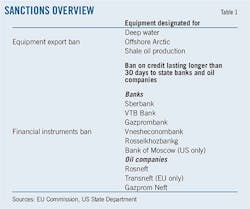

As Fig. 2 shows, however, Russian oil production has so far kept up, and both second-half 2014 and first-quarter 2015 showed year-on-year growth of 0.4% and 0.8%, respectively. These more modest growth rates reflect a slowdown that started well before sanctions, suggesting they have had little immediate impact on Russian oil production. The question is what effect they will have in the longer run.

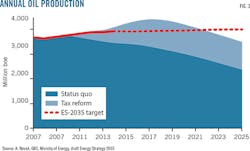

The Russian Ministry of Energy warned already in 2010 that 90% of greenfield and 30% of brownfield resources would be uneconomic under the existing fiscal and legislative framework and that production would therefore decline unless taxes were reduced.1 Energy Minister Alexander Novak reiterated the warning in a government discussion on tax reform in 2012: production remained comfortably high, but maturing fields introduced vulnerability, and increased investment was needed to avoid decline (OGJ Online, Aug. 12, 2013).

Novak introduced two scenarios, both reflecting the main ideas in the General Oil Scheme of 2010, a government strategy document that was drafted but never adopted:

• Do nothing and watch oil production drop.

• Introduce tax stimuli and prompt its rise.

Peak production could be postponed to 2017 and 2010 production levels maintained until past 2022, according to this scheme. The government launched a massive tax break program and production growth stayed on course (Fig. 3).

Novak's report also put forward a list of new fields that would have to come on stream in order to avoid production declines. Should current sanctions impede these projects, the consequence would be reduced production.

Fig. 4 links the Energy Ministry's planned projects and current sanctions. Only one project, Shell and Gazprom's Bazhenov exploration at the Salym fields, is affected by the export ban. The two planned offshore projects are either already in production (Prirazlomnoe) or in shallow water, and therefore largely unaffected by the sanctions (Filanovskogo).

Rosneft and Gazprom Neft, however, which now face credit constraints due to the sanctions, respectively operate 10 and 1 of the 19 fields planned for production. These fields are also the largest, accounting for more than 75% of the total planned new fields' output.

The overview of planned projects in Fig. 4 is not exhaustive (Lukoil for instance has tight-oil projects not listed), but it is clear that Russia does not have any other giant fields short-term. Do Russia's oil companies-and Rosneft in particular-have the financial resources to keep projects on schedule? Or, will they start to slide?

Debt vs. investment

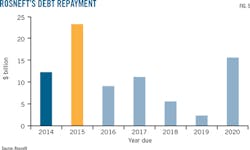

Russia's production outlook appears to hinge on Rosneft and the company's financial ability to sustain its field development program. But the acquisition of TNK-BP in 2013 left the company with significant debt, a large repayment chunk of which is due this year (Fig. 5). This payment normally might have been manageable, but Rosneft is both barred from refinancing in Western markets and faces a substantial revenue shortfall due to the lower oil prices. Rosneft Pres. Igor Sechin stated in February that capital expenditure (capex) would be cut by 30% from 2014 (in US dollars).

Table 2 recalculates key financial statistics for Rosneft for 2015. Assuming production stays at 2014 levels, Rosneft's revenue for 2015 is adjusted so that the relative revenue reduction (in US dollars) from 2014 to 2015 matches the decline of the oil price from the average $98.90/bbl in 2014 to an estimated $60/bbl for 2015. The exchange rate is adjusted to 50 rubles/$ to reflect the oil price's effect on the value of the ruble.

Costs are assumed to be 100% sourced from Russia and subject to zero inflation, keeping nominal operating expenditure (opex) constant in the same way production values were. The exception is gross taxes, which are reduced in line with the oil price and boosted in line with the exchange rate to reflect current gross tax-rate calculation practices.

Converting dollar revenue to rubles and subtracting ruble costs yields earnings before interest, tax, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA). Since gross taxes constitute the vast majority of taxes payable and are already subtracted, this is essentially the money Rosneft retains after selling its products and paying the direct costs of production, which it may then channel to debt servicing or capital investments, for instance in new fields.

According to this example there will be a 50% slide in EBITDA from 2014 to 2015 and a more than 60% reduction as measured in dollars. Rosneft will have $10 billion left after paying production costs, making it difficult to finance both a debt repayment of $23 billion and a planned capex budget of close to $10 billion.

Rosneft has applied several times for investment support from the Russian National Welfare Fund in an effort to close this gap. In September it applied for 1.5 trillion rubles to cover its capital needs for the coming year. Rosneft subsequently raised its application to 2 trillion rubles, refused by the Ministry of Finance, which pointed to a total fund size of only more than 3 trillion rubles, 60% of which was ear-marked for national infrastructure investments.

Rosneft returned early this year with a revised request for 1.3 trillion rubles. But the government is holding back, and it seems Rosneft can expect no more than 300 billion rubles, enough to still make it the welfare fund's largest single investment.2

This level of support will leave a large enough deficit that limiting capex reductions to 30% seems optimistic. Standing $7 billion short of just repaying its $23 billion dollar debt, it is unclear how Rosneft will afford any field development investments at all.

China could serve as an alternative source of financing for Russian oil and gas companies. Gazprom expected to receive $55 billion in the form of advance payment for the $400-billion natural gas pipeline deal with China, but this condition was omitted in final price negotiations.

Tangible results for Rosneft from the Chinese connection have been limited. China National Petroleum Co. and Rosneft have concluded a framework agreement on the former acquiring a 10% stake in Vankor Neft (holding the licenses for Vankor, Suzunskoe, Tagulskoe, and Lodochnoe fields), with unnamed Chinese investors also said to be interested in investing in enhanced oil recovery (EOR) in Rosneft's fields in Ingushetia.

The Vankor deal may provide some relief, but quantifying its effect is problematic. The sales price was not disclosed, nor were updated investment plans for the fields encompassed. Rosneft's Chinese connection can therefore only be loosely assessed and is kept out of the calculations in this article. It is clear, however, that even a 10% Vankor Neft buy-in from China still would not resolve the imbalance between Rosneft's obligations and income.

Outlook

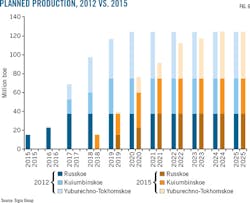

With access to capital markets barred, Rosneft is in dire straits. Without spending 30-50% of the National Welfare Fund to support field development, projects will be postponed. Rosneft has already signaled that development of Russkoe and Yurubechno-Takhomskoe (the two largest fields in Fig. 4) will be postponed until 2019 and 2018. These delays mark 2 and 1-year adjustments to a schedule that had already been revised and may not be the last reschedulings.

Even with government support, therefore, it is hard to see where Rosneft will find sufficient funds for any capital expenditure in 2015. The company also has considerable debt maturing in 2016 and 2017. If the current income situation persists, Rosneft may have to hold back planned investment in those years as well.

The following three scenarios will guide the rest of this article:

• Scenario 1 shows the effect of postponing Russkoe and Yurubechno-Takhomskoe fields for 2 years and 1 year, respectively, as Rosneft has already announced, and also Kuiumbinskoe field for 2 years.

• Scenario 2 presents a more restricted investment outlook than that so far proffered by Rosneft, postponing the same three fields for a full 5 years.

• Scenario 3 demonstrates the effect on Russian oil production should Rosneft choose to stick to its revised investment plan for the three fields in question but do so at the expense of all other investments in new production.

Since Gazprom Neft is also subject to sanctions, it could be included when calculating postponed production in the second scenario. But its modest size compared with Rosneft limits its impact and to highlight Rosneft's importance, Gazprom Neft is excluded.

Scenario 1

Along with Russkoe and Yuburechno-Takhomskoe fields, Vostochno-Messoiakhskoe and Kuiumbinskoe are among the largest in the Energy Ministry's plans for the near future and are also subject to sanctions. Gazprom Neft has also asked for funding from the National Welfare Fund for Kuiumbinskoe (a joint development with Rosneft), and we assume it will also be postponed, for 2 years from 2017 to 2019. Vostochno-Messoiakhskoe appears to be in full development already and is assumed to remain on schedule.

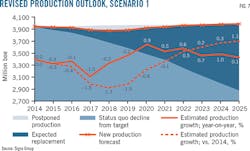

Applying these adjustments and Rosneft's already warned postponements (Fig. 6) yields 370 million bbl of postponed production from 2015 to 2023 compared with the Energy Ministry's 2012 projections, roughly 10% of total 2014 production. Fig. 7 combines the postponed production with data from the Ministry of Energy's 2012 forecast and the draft 2035 Energy Strategy's production forecast (Fig. 3).

The production forecast in the draft 2035 Energy Strategy is chosen as a baseline for the production outlook rather than the ministry's tax reform scenario because the former is more recent and in line with the actual production trend over the last 2-3 years. Production was above target in 2014, however, so that the starting point has been revised to match actual figures and annual growth has been revised to keep 2025 production in line with the forecast.

The decline in production envisioned in the ministry's status quo scenario is interpreted as inherent decline from existing fields that must be replaced to maintain production levels and subsequently subtracted from the revised forecast to derive expected production replacement.

Production in Fig. 6 is also postponed to reflect changes in timing for the three projects shown, leading to a 9-year dip below targeted production. Production will decline every year until 2018, when it will be 1.7 % below 2014 (Fig. 7).

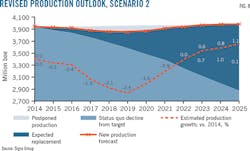

Scenario 2

Once a project has been postponed, it often gets postponed again. Given Rosneft's capital constraints, it would not be surprising if this happened to Russkoe, Yuburechno-Takhomskoe, and Kuiumbinsko.

Fig. 8 presents a scenario in which production at these three projects is delayed for 5 years until 2020. Production will decline year-on-year up to 2018 and by 2019 be at least 2.5% lower than 2014 production. This still rather conservative adjustment yields a total postponed production of roughly 530 million bbl, 44% more than in Scenario 1 and equivalent to 13% of Russia's 2014 production.

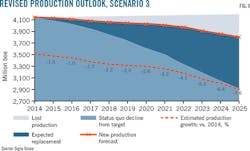

Scenario 3

Both Scenario 1 and Scenario 2 assume that Russian production will return to targeted levels after production from postponed fields reaches planned levels. But for this to happen, production growth must be stronger after postponed fields come on stream than if they had not been postponed at all.

This presumes that other planned developments continue at full speed in addition to the developments that were postponed, implying increased investment capacity after the postponement. Given that the rationale for postponing projects in the first place is limited investment capacity, it seems counterintuitive that the investment capacity should be greater than planned later, particularly after a period of lower revenue due to production decline and a lower oil price.

A more plausible outcome is that when resuming development of the postponed fields, Rosneft will sacrifice other investments. These could include the remaining seven Rosneft fields in Fig. 4 as well as EOR and other smaller developments not included in the ministry's 2012 plans.

In Fig. 9, Rosneft continues work on Russkoe, Yuburechno-Takhomskoe, and Kuiumbinskoe fields according to the schedule in Scenario 1, but to do so it sacrifices all other investments until 2025. In this scenario, limited investment capacity causes the sanctions-induced field postponements to bring Russian production into long-term decline, 2 years earlier and starting from a substantially lower level than envisioned in 2012 (Fig. 3). From 2014 levels, Russian production decreases on average 0.7 %/year, resulting in 7% lower production by 2025.

Actual decline, however, may turn out to be greater. Gazprom Neft's request for government support suggests it is facing similar problems, and Lukoil has also signaled that capital expenditure will be cut 20-25%.3 In sum, more fields and EOR projects are likely to be delayed, increasing the amount of postponed (and potentially lost) production.

Lower oil prices also contributed to these effects. For companies with limited debt such as Gazprom Neft or companies not subject to sanctions such as Lukoil, the oil price in fact may be the main driving force. But for Rosneft, sanctions are the biggest difficulty. If Rosneft could refinance its maturing debt, it would have sufficient operating income to support its revised investment program. With capex and opex both near $5.00/bbl,4 supporting investments through credits would have been possible even at $50-60/bbl crude prices.

References

1. "General Development Scheme, Oil Industry of the Russian Federation for the Period Until 2020," Ministry of Energy, Russian Federation, June 2010.

2. Lyutova, M., Papchenkova, M., and Starinskaya, G., "Government decides how much money Rosneft needs from FNB," Vedomosti, Apr. 14, 2015.

3. Fedun, L., "Financial Results, First-quarter 2015," Lukoil, Moscow, June 2015.

4. "Q4 2014 IFRS financial results presentation," Rosneft, Mar. 4, 2015.

SANCTIONS OVERVIEW

Sources: EU Commission, US State Department

Table 1

ROSNEFT 2015 FINANCIAL OUTLOOK1

1At $60/bbl crude. 2Analysis from: Conerly Consulting LLC, University of Stavanger, Oil-Price.net, Nordea, Barclays, DNB Markets, and ABN AMRO.

Sources: Rosneft, Sigra estimates

Table 2

TECHNOLOGY

The authors

Daniel Fjaertoft ([email protected]) is managing director at Sigra Group, Oslo. He previously served as a petroleum analyst at Econ Poyry and advisor on petroleum and maritime issues at the Barents Secretariat. He holds a MS in economics from the University of Oslo.

Indra Overland ([email protected]) is head of the energy program at the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs, Oslo. Before that he headed the Russia, Eurasia, and Arctic Department at the same institute and was a senior advisor to Nordforsk. He holds a PhD from the faculty of earth sciences and geography at the University of Cambridge.

More Oil & Gas Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com