Tajikistan: Pamir pipedream or new Central Asian exporter?

Gabe Collins

Bo White

University of Michigan Law School,

Ann Arbor

Tajikistan is energy starved—a situation that results in up to 70% of the population suffering from severe power outages each winter, imposes an estimated annual economic hit of around 3% of GDP,1 and causes unsustainably high rates of indoor air pollution and deforestation due to overreliance on fuelwood.

On top of all of this, over the past year, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan's primary gas source, has repeatedly disrupted its supply to Tajikistan as a result of increased demand from China.

Yet, this small impoverished country's energy woes could become history. A recent deal that saw China National Petroleum Corp. (CNPC) and Total SA farm into Tethys Petroleum's exploration project in southwestern Tajikistan suggests that over the next 5 years Tajikistan could potentially become a major exporter of gas and possibly oil.

Will Tajikistan become Central Asia's new PetroTitan, or will the current gas resource promise prove to be a pipedream in the Pamirs?

The evidence increasingly suggests that the country has the geology to be a titan, but it will face steep challenges to produce and bring gas to market.

There are also many uncertainties in regard to how the country will be able to manage the socio-political challenges that can accompany huge revenue inflows into a small economy.

Current state of play

Gazprom and Tethys Petroleum are the primary firms conducting oil and gas exploration in Tajikistan.

Tethys focuses on oil and gas exploration and production in Central Asia and the company's shares trade on the Toronto, London, and Kazakhstan stock exchanges.

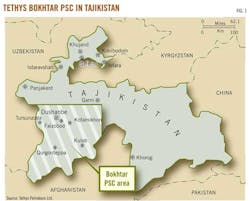

Gazprom has nearly finished drilling the Shakhrinav-1P gas well, which at 6,300 m total depth will be the deepest in Central Asia. Part of the reason the well is so deep is that gas in the Bokhtar region where both companies are exploring is believed to lie beneath a thick salt layer. The Bokhtar area is large, occupying 35,000 sq km in southwestern Tajikistan (Fig. 1).

In December 2012, Total and China National Oil and Gas Exploration and Development Corp. (CNODC), a subsidiary of CNPC, agreed to farm into Tethys' Bokhtar production sharing contract, with each holding a 33% stake. The fact that Tethys has been able to bring in these major international players suggests that the project is very compelling, despite the various geological, regional, and country risks.

Reserves likely large, wells challenging

Independent estimates from Gustavson Associates currently place Bokhtar's unrisked mean prospective recoverable resources at 114 trillion cu ft of gas and 8.5 billion bbl of crude oil and-or condensate.2

As such, Tajikistan's gas and oil reserve base could ultimately prove to be on par with that of the world class offshore discoveries being made in Mozambique and Tanzania.

The depth of Tajikistan's subsalt strata (more than 6,000 m) will make drilling expensive. Historical research data suggest the wells will probably cost more than $40 million apiece, and perhaps closer to $50 million to drill and complete.3 Thus, wells will need to be highly productive in order to be economically viable.

Other areas in the Amu Darya basin of Central Asia have yielded highly productive gas wells—for instance CNPC's Oja-21 well on the right bank of the Amu Darya River in Turkmenistan flowed nearly 51 MMcfd of gas when tested in September 2010.4 Ultimately only the drill bit will tell what Tajikistan has, but other global geological examples of subsalt oil and gas developments offer cause for optimism.

With a substantial reserve base likely in place, the next questions are: (1) How much gas does Tajikistan have the potential to produce? And (2) what is a realistic timeframe for the completion of the infrastructure necessary for Tajik gas to reach international markets?

A conservative estimate assumes Tajikistan's actual economically recoverable gas resource at 23 tcf—20% of the total gas reserves Gustavson Associates believes the country holds. As a comparison, Ophir Energy—a major East Africa focused gas producer—reports that for its LNG projects, 3.8 tcf of recoverable gas reserves can support 450 MMcfd of gas production over a 20 to 25-year project life. On this basis, Tajikistan could likely eventually sustain production of 2.5 to 3.5 bcfd of gas depending on how large reserves ultimately turn out to be.

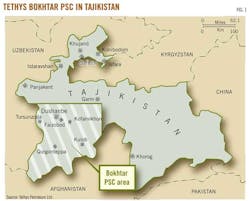

We believe Tajikistan will first supply its domestic gas market, which in 2011 required 22 MMcfd, according to the US Energy Information Administration. The remainder will be available for export, and so by 2020 Tajikistan could export nearly as much gas to China as Turkmenistan does now—2 to 2.5 bcfd (Fig. 2). We expect Tajikistan's internal gas use to remain relatively low even if large fields come online because distance from markets and rising value of the local currency will stifle large-scale local chemical and heavy industry development.

This would make Tajikistan China's second largest source of Central Asian gas after Turkmenistan and by itself would justify building an additional parallel pipeline along the existing Central Asia-China gas pipeline corridor. It would also be enough gas to fuel twenty 1,000-Mw gas-fired power plants and replace 35 million tpy of coal use.5

Moving Tajik gas to market

The most logical export pipeline route would be northwards out of Tajikistan, through Kyrgyzstan, and to the Central Asia-China gas pipeline in Southern Kazakhstan (Fig. 3).

The rationale for this route is two-fold.

First, at something like 900 km it is much shorter and cheaper than building a route directly to China, which would require a roughly 2,000 km pipeline to be built across the Pamirs, one of the highest mountain ranges on earth.

Second, it is advantageous for a gas producer to sell into a hub, which is what southern Kazakhstan is becoming for China-bound gas as supplies from Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan are integrated into a common pipeline corridor heading for the Chinese border crossing at Horgos, Xinjiang.

Tajikistan faces an uphill fight for negotiating a gas sales price with China. Turkmenistan, the first to sign a supply deal with China (in 2009), was receiving $10.22/MMBtu for gas sold to China in August 2012, whereas Uzbekistan was receiving from China only $9.17/MMBtu at this time, according to Platts.

Tajik gas will likely be discounted more deeply relative to the Turkmen baseline price than Uzbek gas was. The wellhead price of natural gas in Tajikistan remains to be seen, but we anticipate that CNPC would be willing to pay $7-8/MMBtu for Tajik gas delivered to the hub in southern Kazakhstan.

How long to place Tajik gas on line?

Developing a major natural gas field in a greenfield area without existing infrastructure is a complicated and multiyear undertaking.

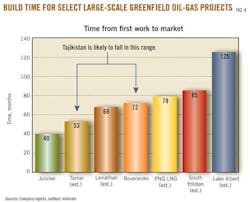

The development of Turkmenistan's massive South Yolotan gas field provides a contemporary example. The Turkmen government announced South Yolotan's discovery in November 2006, and the field is likely to deliver its first gas into the Central Asia-China gas pipeline in December 2013, according to Petrofac, one of the project's main contractors—a total time of 85 months (Fig. 4).

Dilatory decision-making by the Turkmen government was a key factor in how long it has taken to develop South Yolotan's resources and bring the field online.

We expect the development and production of Bokhtar gas will proceed much more rapidly than that of South Yolotan due to Tajikistan's acute needs for domestic energy and economic growth, the increasing tensions with Uzbekistan, the existence of Chinese financial support, and Pres. Rahmon's strong personal support for the project.

Assuming no major unforeseen opposition or technical snags, a timeframe of 4-6 years from first commercial drilling to commercial scale gas exports is realistic.

Political risks, local buy in, sustainability

With respect to drilling operations, eventual production, and the long-term sustainability of the project, it will be vital for operators and the Tajik government to maintain political stability and gain the support of those living near the gas fields as well as the support of the population at large.

Tajikistan's security situation has remained relatively stable since its 1992-97 civil war; however, in recent years the country has experienced minor flare-ups in the Rasht Valley and in the Pamir region. These events were relatively isolated and took place in areas that are geographically and culturally distinct from the project site.

Of greater concern is the increasing level of general discontentment with the Rahmon government. In 2011, Time Magazine listed Rahmon in eighth place on its ‘Top 10 Autocrats in Trouble' report,6 describing him as "govern[ing] Tajikistan as his personal fief" and suggesting that "dark clouds hover over the future of Rahmon's Tajikistan."

More recently, Rahmon made international headlines for his media censorship policy (in particular for blocking Facebook),7 which many analysts view as a move to suppress the growing number of political dissidents in the lead up to Tajikistan's general elections in November of 2013—an event that will be telling for potential investors.

The projects' proximity to Afghanistan also raises some concerns. While the northeastern region of Afghanistan is considered one of the most stable in the country, the Tajik-Afghan border is highly porous and is one of the main conduits of the Afghan narcotics trade.

Furthermore, the recent events at the Amenas complex in Algeria, in which Islamist militants exploited that country's porous border with Mali to infiltrate and seize the gas facility, stresses the need for a regional perspective on security risks. This concern is further highlighted by the ongoing withdrawal of US and NATO troops from Afghanistan.

Another key consideration will be how the Tajik government manages the potentially massive inflow of royalties, and in particular to what degree the population perceives that they are receiving their fair share from the project.

Examples of the socially disruptive nature of such inflows to impoverished nations are plentiful, and the Tajik government should carefully study the resource revenue management debacles of nations such as Nigeria, as well as countries that used newfound resource wealth to establish a trajectory of economic and social growth, such as Singapore.

The government would be well advised to ensure royalties are used to make significant and concrete improvements in people's lives from the outset. Bringing the country's dismal transportation and electricity infrastructure, as well as its education and health services, up to international standards would be a good start.

The participation of Total, which has substantial skill and expertise in managing the corporate social responsibility aspects of oil and gas projects, will be very helpful to the Bokhtar project's ability to win local hearts and minds.

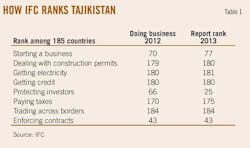

International indices paint a troubling picture for companies attempting to navigate Tajikistan's bureaucracy (Table 1). The International Finance Corp.'s 2013 Doing Business report ranks Tajikistan 180th of 185 countries for dealing with construction permits, 181st for getting electricity, and 184th for trading across borders (higher numbers being worse).

Similarly, Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index places Tajikistan at 157th out of 176 countries (higher rankings being more corrupt), and the World Bank's ‘control of corruption' indicator puts Tajikistan in the world's bottom 9th percentile. These structural problems would be compounded by Tajikistan's lack of skilled labor and inexperience with the oil and gas industry.

The geology and economics of the Bokhtar project are promising, and the fact that two of the largest and most experienced petroleum companies in the world are onboard clearly suggests Tajikistan has the geological potential to become Central Asia's next PetroTitan.

However, if the Bokhtar project is to come to fruition in the near future, the government and the operators need to take seriously the fragility of the Rahmon regime and account for the significant socio-economic impact the project will have. To hedge these risks operators must implement robust social and development programs and outside governments should offer Tajikistan advice to help it address structural problems in the Tajik economy.

If the political risks can be kept under control, potentially huge Tajik gas reserves and strong political and economic support from China—the principal market for the gas—bode well for the development of production and gas exports.

References

1. (http://siteresources.worldbank.org/ECAEXT/Resources/TAJ_winter_energy_27112012_Eng.pdf).

2. (http://www.tethyspetroleum.com/tethys/newscontent.action?articleId=2535594).

3. (http://cce.cornell.edu/EnergyClimateChange/NaturalGasDev/Documents/CHEME%206666%20Lecture%20Series-2011/CHEME%206666_07_Drilling%20Lecture.pdf).

4. (http://www.rigzone.com/news/oil_gas/a/99370/CNPC_Discovers_High_Gas_Flow_at_Turkmen_Well

5. (http://www.rrc.state.tx.us/about/initiatives/naturalgasstudy/presentations/texasindenergy.pdf).

6. (http://www.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,2045407_2045416_2045448,00.html).

7. (http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/11/27/net-us-tajikistan-facebook-idUSBRE8AQ0JY20121127).

The authors

Gabe Collins ([email protected]) hails from the US Permian basin and has worked in government and as a private sector global commodity analyst at a major investment fund and investment advisor. He is a graduate of Princeton University and is currently a Juris Doctorate candidate at the University of Michigan Law School.

Bo White is an international development and corporate social responsibility professional who has spent significant time working with communities, international organizations, and governments in Tajikistan, Papua New Guinea, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Nepal, and Afghanistan. He speaks Tajiki and Farsi. He is currently working towards his Juris Doctorate degree at the University of Michigan Law School, where he focuses on international project finance and due diligence.