Iraq poised for key role in global energy sector

Justin Dargin

University of Oxford

Oxford, UK

Over the past few decades, Iraq has rarely been featured in the news for positive developments. However, a revolution is in the works as the country is busy building a bright future on the back of its rapid improvements in the energy sector.

Iraq has the world's fourth largest global oil reserves after Saudi Arabia, Canada, and Iran, amounting to 143.1 billion bbl at the end of 2011.1 However, due to Iraq's history of wars, sanctions, underinvestment, and invasion over the past several decades, it may discover significantly more oil on its territory as just a small proportion of the country has been adequately explored, much less developed.

Iraq is still overwhelmingly a "petro-state," meaning that it is a state that is nearly totally dependent on oil for its economic and domestic energy needs. Iraq's energy demand is overwhelmingly supplied by oil, comprising about 94% of domestically consumed energy. In terms of its economy, oil export makes up about two-thirds of its GDP.2

Stunning oil turnaround

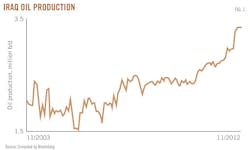

In a stunning turnaround, Iraq recently stabilized and increased its oil production, whereby at the end of 2012, it reached nearly 3.35 million b/d (Fig. 1).

In 2012, Iraqi oil production posted gains of nearly 650,000 b/d, comprising the largest annual gain in 14 years. In total, Iraq is producing the largest amount of oil in 3 decades, since the period when Saddam Hussein first came to power.

Iraqi policymakers are planning further oil production expansion to increase production to 3.7 million b/d in 2013. Iraq's production increases have matched the relative production decreases in Iran.

As a result of Iranian oil production declines, Iraq became the second largest OPEC producer in late 2012. As Iran's production slides exponentially due to domestic consumption increases, international sanctions, and reservoir declines, Iraq has been able to absorb the Islamic Republic's market share to its economic benefit.

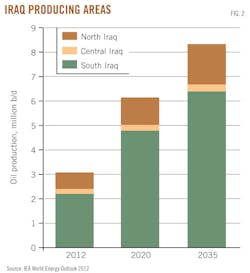

The IEA forecasts that Iraqi production will double by 2020, reaching approximately 6 million b/d. By 2035, the IEA estimates that Iraqi production will reach 8.3 million b/d (Fig. 2).3 But, the 2020 forecast is only half of Iraqi official targets of 12 million b/d of production by 2017. The International Energy Agency notes that Iraq production will be assisted by "high oil reserves, easy geology and low production costs." Nonetheless, it still cautions, as will be discussed below, notable challenges remain in order to meet the official Iraqi production goals.4

In terms of natural gas, Iraq is not a significant producer and contained about the 10th largest reserves in the world (3.6 tcm/126.7 tcf) as of the end of 2011.5 Most of Iraq's gas reserves are in the south of the country, contained in the mostly Shiite (and somewhat volatile) province of Basra. At the end of 2011, Iraq produced about 1.9 bcmd/67 bcfd.

Some of Iraqi gas is consumed in oil reinjection and power generation. However, Iraq still flares a large amount of its associated gas (especially in Basra) due to insufficient infrastructure for consumption and export.6 Gas flaring is a major problem for Iraq as it is estimated to cost the country approximately $5 million/day, as well as the opportunity cost of using precious oil for power generation instead of gas.6 Because of extensive flaring, Iraq's five gas processing plants, with a combined capacity of 773 bcf/year, are often nonoperational.

As Iraqi oil production climbs, gas flaring will likely increase in the short to mid-term, rising from the present rate of 19.8 MMcmd (700 MMmcfd). To adequately manage the large economic cost of flaring its gas, Iraq successfully negotiated a series of agreements with international oil companies to reduce flaring over the next several years in order to redirect gas production to domestic consumption and meet the country's pressing power requirements.

Iraq needs about 70% more net power generation capability to meet its power demand. The IEA estimates that if new power generation capacity materializes on schedule, then Iraq will be able to satisfy power demand by 2015.7 However, until gas production increases, power generation will continue to be supplied by relatively inefficient (and high opportunity cost) oil-fired power plants.

Iraqi energy outlook to 2020-40

Major oil expansion on the horizon

Iraq has been increasing oil production every year since 2005.

The country's major strategic goal is to rival Saudi Arabian production. Although with its pressing economic needs, a significant amount of oil will still be consumed domestically until 2020 unless Iraq can rapidly increase its gas production for internal consumption.

Under a relatively conservative forecast, Iraqi oil production will likely grow to 6 million to 7 million b/d by 2020 and by 8 million to 10 million b/d to 2035-40. Of course, in order to increase oil production to those amounts, Iraq will have to greatly increase investment, reduce corruption, improve security, as well as resolve the political differences (in reality, deadlock) with the semiautonomous Kurdish region (Kurdistan Regional Government).

Iraq has already made substantial inroads in partially resolving some the aforementioned issues, and while the political and economic situation is still quite delicate, IOCs and NOCs indicated no shortage of interest in pouring major investment into Iraqi oil fields.

By 2020, based on current trends, it is likely that Iraq will resolve the most pressing differences with the KRG, thereby freeing that region for significant investment from the super majors and adding to total national oil production.8

If Iraq's current progress continues and it increases investment from the current $9 billion to an annualized $25 billion for the rest of the decade, then by 2020 it could become the world's second largest exporter, overtaking Russia and responsible for the growth of nearly half of estimated incremental global production.

As Iraqi oil production increases, it will be able to create the type of spare capacity that historically characterized Saudi Arabia for many decades. And, as Saudi Arabian oil dominance erodes because of rising energy intensity and domestic demand, as well as oil field declines, Iraq will likely be a close rival to Saudi Arabia if not completely supplanting the Saudi position as global swing producer by 2040.

In the long-term, depending on the health of the global economy, and Iraq being able to continue its development of the hydrocarbon sector, Iraqi foreign revenue could reach $5 trillion (approximately $200 billion/year) from oil exports until 2035-40.3

Developing Iraqi natural gas

Iraq is also planning significant growth in natural gas production.

It is likely that Iraq will meet its stated goal of producing 5 million cu m/day (194 MMcfd) by 2017-18 as it is rapidly increasing its oil production while reducing flaring. In particular, Iraq is hoping that the gas production deal agreed upon with Mitsubishi Corp. and Royal Dutch Shell in 2011 to produce and process gas from Iraq's southern oil fields will lead to significant production increases.9

Expanding Iraqi gas production will have the added benefit of conserving more oil for future export. Iraq's strategic goal after meeting domestic deman is to maximize the monetization of any potential gas exports, and therefore, export to markets that would pay the highest premium and have the most durable demand rates.

Yet, if Iraq desires to meet its expected long-term gas demand increases of 70 bcf/year by 2035-40, and have enough gas to export, it will need to create proper financial and regulatory incentives for nonassociated gas production.

In terms of potential export, Iraq is considering two strategies. One is liquefied natural gas, while the other is based upon pipeline export.

For example, in May 2011, Iraq entered into a strategic energy partnership with the European Union in which Iraq agreed to an assessment of possible pipeline export opportunities (potentially through Nabucco, the Arab Gas Pipeline, or some other route) to the EU in exchange for a guaranteed market for Iraqi gas.10

In January 2010, the Iraqi minister of petroleum and the head of the European Energy Union for Strategic Cooperation with the EU signed a memorandum of understanding for potential Iraqi supply to Europe through the Nabucco pipeline. However, an MoU has no legal force and is mostly aspirational. Moreover, the Nabucco pipeline has met with extended delays and is not yet certain to come online.

Iraq also is looking into export potential to the gulf as the region is facing a significant gas shortage. But, the gulf countries have not yet liberalized their domestic gas prices. They therefore have a fair amount of resistance to paying international market rates. The gulf countries' desire for below international market rates for gas imports, by neccessity, reduces Iraq's appetite to supply this market in the short to mid-term.

At least for the mid-term, i.e., 2020, Iraq will prioritize domestic supply of gas with no likely exports unless and until its domestic demand is satisfied. At current rates of production, satisfaction of domestic gas demand will likely occur in the early to mid-2020s.

The IEA predicts that Iraq could have initial amounts of gas surplus for export by the 2020s, reaching 20 bcm/706 bcf by 2035.7 After reaching that milestone, Iraq would weigh the strategic choices of developing its downstream industries for economic diversification and job creation or export to international markets for crucial hard currency generation.

Faced with these choices, it is likely that Iraq would opt for downstream industrialization to diversify its economy and create jobs. Additionally, if current trends continue, by 2020, significant amounts of LNG are poised to enter the global market (US, Africa, Latin America, Australia, Africa), potentially causing a supply glut, making export at relatively low prices distinctly unattractive in the mid-term.

Moreover, the current administrative pricing and subsidization framework for energy allocation will likely endure until the beginning of the next decade as the government attempts to tackle the energy poverty of its citizens. Energy subsidization, as many gas-rich countries experienced, creates substantial disincentives for investment. Nevertheless, with robust economic growth from political stability and increased foreign revenue, Iraq would likely begin to move away from domestic energy subsidization by the long term.

Geopolitics of Iraqi energy dominance

Taken as a whole, increased Iraqi oil export will be beneficial to the global market as it would expand available oil supply and cushion emergent market tightness.

Furthermore, increased Iraqi oil would moderate the international oil price. However, lower international oil prices are a double-edged sword for the US strategic interests. On one hand, increased supply, and the resultant lower prices, would be of benefit to US consumers. On the other hand, as the US increases its unconventional oil production, which has a much higher production cost, a lower international oil price would be injurious to US oil producers who struggle with a much higher breakeven prices per barrel of oil when compared with their Middle Eastern counterparts.

Nonetheless, American foreign policy objectives would be largely met with a much more stable and economically successful Iraq that is firmly integrated into the international community.

There is also the added benefit for the US in that producers that do not support American strategic objectives, such as Russia, Iran, and Venezuela, would have a much more difficult time with expanded oil supply in the global market as their economies are much more dependent on high international oil prices.

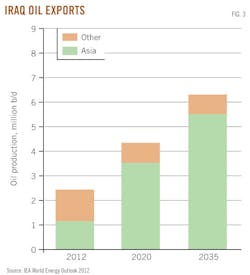

One of the main beneficiaries of Iraqi oil export expansion would be the rapidly growing Asian economies, especially China, as China seeks to partially secure its energy security through Iraqi oil imports.

Also, Chinese NOCs have fared quite well in bidding for Iraqi production contracts. The IEA predicts that by 2020, Iraq will export 80% to Asia (Fig. 3).7 11 This process rides in the wake of the downturn in US crude imports and the increase of oil exports to China from other regions as well, such as Africa and Latin America.

US crude imports declined to 8.7 million b/d in 2012 from 8.9 million b/d in 2011.12 This is the lowest amount since 1998. A clear structural evolution has been afoot in the global oil sector that is witnessing a clear preference for the Asia/Pacific region from the Atlantic Basin. For example, it is forecast that China will increase imports of West African oil by 18% in 2013.12 This increase comes on top of the 16% gain posted in 2012.12 The same shift can be seen with Saudi Arabia.

In 2009, due to the sharp downturn in oil consumption in the US due to the global financial crisis and to the increased production from domestic US oil supplies, for the first time Saudi Arabia exported more oil to China than to the US.13 Exports to the US dropped to 989,000 b/d, the lowest level for 2 decades. In terms of China, oil exports reached above 1 million b/d, almost double from 2009.13 Saudi Arabia currently accounts for nearly a quarter of Chinese oil imports.

As mentioned above, the increase in Saudi oil exports to China represents a deeper structural shift in the global energy sector and a steady transition away from dependence on Western markets (US and Europe) to East Asia for Saudi Arabia.

It is estimated that Chinese imports of Saudi oil will increase by 11% (120,000 b/d) in 2013 to 1.17 million b/d.14 The sharp increase in Chinese imports from Saudi is due to Chinese efforts to transition away from Iranian oil imports to a more stable supplier, as well as efforts to build strong bilateral relations with such major oil producers.

Other Asian consumers, such as India, South Korea, Taiwan, and Japan, also reached out to Saudi Arabia in a bid to stabilize oil imports. Therefore, Iraq is not unique in its expected shift to dependence on Asian markets; it is merely one link in an extensive chain of global oil production centers gearing their production to the East.

Yet, in terms of gas, it is likely that Iraq will not begin to have significant gas export capability until the mid-to-late 2020s as it focuses on supplying the domestic market. However, by 2040, Iraq will likely have a diversified downstream industry and gas export portfolio with both LNG and pipeline exports to its neighbors (principally, the gulf), Asia (LNG), and the EU (pipeline).

As it is likely that the US will begin to export significant amounts of LNG within a decade, Iraqi natural gas exports would have a potentially detrimental impact on US gas export by increasing competition (thereby driving down prices) in the global gas sector and competing with the US for customers (if the US begins to export natural gas in earnest).

Despite the main challenges it faces, it is obvious that Iraq has made enormous strides since the years when its hydrocarbon sector was stifled by failed policies and outright destruction during its many conflicts. Now, Iraq is poised to play a major role in the global energy sector over the next decade. And, at that time, it is more than likely that Iraq will set the tone in the global oil sector.

References

1. BP Statistical Review of World Energy, oil production, June 2012, p. 9.

2. "Iraq Country Analysis Brief," US Energy Information Administration, September 2010.

3. "Iraq Energy Outlook," International Energy Agency, 2012, p. 1.

4. Chazan, Guy, and Blas, Javier, "IEA predicts boom in Iraqi oil production," Financial Times, Oct. 9, 2012.

5. BP Statistical Review of World Energy, oil production, June 2012, p. 20.

6. Lee, John, "Gas flaring costs Iraq $5 million a day," Iraq Business News, Nov. 19, 2012.

7. "Iraq Energy Outlook," International Energy Agency, 2012, p. 2.

8. Dargin, Justin, "Securing the peace: The battle over ethnicity and energy in modern Iraq," working paper, Dubai Initiative, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School, November 2009.

9. "Shell, Mitsubishi eye Iraq's natural gas," UPI, July 13, 2011).

10. "Iraq realizes its natural gas potential and hopes to export to EU," The National, Sept. 12, 2011.

11. Neville, Simon, "Iraq could become world's second biggest oil exporter," The Guardian, Oct. 9, 2012.

12. Bockmann, Michelle Wiese, "African oil flows seen shifting to Asia as US imports drop," Bloomberg, (Jan. 8, 2013).

13. Mouawad, Jad, "China's growth shifts the geopolitics of oil," New York Times, Mar. 19, 2010.

14. Aizhu, Chen, and Hua, Judy, "China seen raising Saudi oil imports 11% in 2013 trade," Reuters, Dec. 7, 2012.

The author

Justin Dargin ([email protected]) is an energy and Middle East scholar at the University of Oxford. He was a former research fellow with The Dubai Initiative at Harvard University, where he won a Harvard award for his research into the Gulf energy/power sector. He has worked in the legal departments of Owens Corning and OPEC. He has advised some of the world's largest IOCs/NOCs as to stratgic investment. He is also is a member of the United Nations Alliance of Civilizations as a global energy expert. He is fluent in Spanish, English, and Arabic.