Oil production capacity-building experience has implications for Libya

Anas F. Alhajji

NGP Energy Capital Management

Irving, Tex.

When will Libya restore its precrisis production level of 1.6 million b/d?

This article is an update of another by the same author entitled, "Oil production capacity experience has implications for Iraq" (OGJ, Nov. 3, 2003, p. 20). The earlier article was, given the time of its writing, prophetic in many ways.

This article incorporates Iraq's experience in oil production capacity building since 2003 and adds Nigeria.

Several factors will determine the amount and the speed of Libyan production increases, including:

• The degree of destruction of oil facilities and pipelines.

• The degree of exodus of critical specialized personnel and the conditions of their return or replacements.

• The degree of decisiveness or level of priority given by the transitional government by allocating resources to the oil and gas sectors, including the legal, administrative, and financial requirements.

• The degree of effective assistance, if any, by friendly countries.

Other factors include the global economic situation, OPEC reaction and its willingness to make room for Libya's crude, and the type of contracts with the international oil companies (IOCs).

While some experts argue that Libya owns large financial assets abroad, and therefore it has the financial resources to support oil production restoration, others question this claim. The financial crisis, the massive losses of certain ventures with global investment banks, and the uncertainty regarding the ability to reclaim all foreign assets make the amount of capital available significantly smaller than expected.

In addition, the oil sector has to compete with other important and immediate needs of the population for resources.

Experts agree that it will take time to restore Libya's oil production, but they disagree on the timing, mostly because they assign different weights to the factors mentioned above.

This review is intended to shed some light on the time needed to expand capacity in five countries that suffered from political turmoil: Iran, Russia, Nigeria, Kuwait, and Iraq. The experience of these countries shows that restoring production or increasing production meaningfully needs 21⁄2 to 7 years.

A pattern of 3 years has appeared to be the rule of thumb.

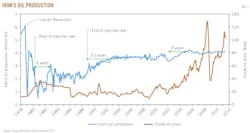

Iran after the war

Labor strikes and subsequent political turmoil and revolution stopped oil production in Iran but did not damage production capacity (Fig. 1). Iran increased its production quickly once workers went back into the oil fields, however, at a much lower rate. The lower production rate was designed even before the revolution because production at 6 million b/d was not sustainable. It was determined in 1978 that production must decline by 50%, to 3 million b/d, to preserve the integrity of the oil reservoirs.

The Iraq-Iran war started on Sept. 23, 1980, after Saddam Hussein had unilaterally canceled a 1975 treaty with Iran 6 days earlier. The war led to another complete halt of Iranian production. The combination of production cuts to curb decline rates, labor strikes, the Iranian Revolution, and the start of the Iraq-Iran war increased the world price of crude oil from around $12/bbl in 1978 to more than $35/bbl in January 1981.

Iraq inflicted major damage on Iran's oil facilities (refineries, pipelines, storage facilities, etc.), which limited Iran's production capacity. However, one of the major effects of the war on Iran's oil industry is not related to bombing of facilities but to corrosion in facilities that were abandoned for fear of attacks or neglected for lack of money or bad decisions.

Under financial pressures, the Iranian government embarked on a desperate program to restore oil production capacity. Iran raced furiously against time to restore its production to acceptable levels, but it still took 3 years to increase its capacity to the levels that prevailed at the beginning of the war (Fig. 1). These efforts were remarkable because Iran increased production despite economic sanctions and the war in an environment of low oil prices.

The war ended in August 1988. It took Iran more than 3 years to increase capacity by 1 million b/d and 4 years to reach sustainable levels. Even after achieving political and economic stability, it took Iran more than 3 years to increase production capacity by about 500,000 b/d between 2002 and 2005.

Economic sanctions on Iran have contributed to the slow growth in production capacity during this period. It is worth noting that Iran's production capacity has not recovered to the prerevolution level of 6 million b/d, mostly because of the belief that the old production level of 6 million b/d was not sustainable. In addition, the production target changed when the war ended from 3 million b/d to higher levels because of massive population growth and rebuilding of destroyed infrastructure by the 8-year war with Iraq.

Kuwait after liberation

Despite political stability and the availability of capital, technology, and international support and expertise, it took Kuwait 21⁄2 years from the day of liberation to fully restore its capacity (Fig. 2).

Despite stability and strong political will to increase production, it took about 41⁄2 years to increase production capacity to the current level of 2.8 million b/d.

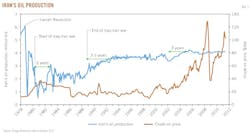

Russia after the Soviet fall

Maturing oil fields, lack of advanced technology, poor management, corruption, and the collapse of the Soviet Union led to a sharp decline in Russia's oil production after 1991.

Russia's production continued to decline despite the restructuring efforts that began in 1993 and the privatization that started in 1995. Political and economic instability, corruption, a poor record of corporate governance, an unstable legislative framework, and lack of legal protection for foreign investors are among the factors to blame for the decline in production during this period.

The financial crisis in August 1998 marked a turning point for the Russian oil industry. Reforms, accompanied by political and economic stability, and devaluation of the ruble created a better investment climate and lowered exploration and development costs.

Russia's oil production capacity started to increase in 1999. However, despite political and economic stability, reform, privatization, higher oil prices, lower costs, and the availability of capital, it took about 3 years to increase oil production by about 1 million b/d (Fig. 3).

It took another 3 years to increase production by 2 million b/d. The trend did not continue: it took 6 years to increase production by only 500,000 b/d, but it was enough to make Russia the world's largest oil producer.

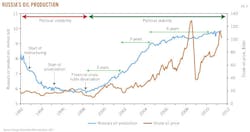

Nigeria ups and downs

Nigeria's oil production is among the most volatile in the world, mostly because of politics and insecurity of workers and assets.

Oil production continued to decline in the first half of the 1980s, but Nigeria was not able to restore the 1980 production until 1993. Corruption of the civilian government and then the military coups that followed in the first half of the 1980s made Nigerian oil production very volatile.

However, a combination of factors reduced Nigeria's oil production capacity significantly in 1986, including International Monetary Fund-induced reforms that led to the political unrest that forced the government to change course, reduction in investment in upstream, and production decline in mature oil fields in the Niger Delta.

It took 3 years, until late 1989, to restore production to previous levels. It took another 31⁄2 years, until 1993, to increase production by a further 500,000 b/d, but production declined again in 1993 as violence erupted in the streets when the military government nullified an internationally-certified election.

Production recovered briefly in late 1993 only to plummet again in 1994 as unrest and labor strikes became widespread in the Niger Delta, especially in the Western division and the Ogoni Land. The fields in the Ogoni Land were abandoned for security reasons.

Although Nigeria's production increased greatly about 4 years later, the increase came from new offshore areas. Deepwater production replaced shut-ins and production decline from mature onshore fields.

The change in government from military control to civilian control and a temporary peace in the Niger Delta contributed to higher production during that period.

After increasing to levels that had not been seen in a long time in 2005, production declined, especially in 2007 and 2008, as violence erupted in various areas. For example, in March 1997, Shell was forced to shut in more than 600,000 b/d of production. By May, more than 750,000 b/d were shut in by several companies. More production was lost in June and July. It took about 3 years to restore production.

While the recent decline in production is attributed to instability in the Niger Delta, the increase in production in 2010 and 2011 is attributed to relative peace and the amnesty program instituted by the late president Yar'Adua, who was elected in mid-2007, for the restless youth in Niger Delta. Cycles of violence and stability indicate a pattern of at least 3 years to restore production (Fig. 4).

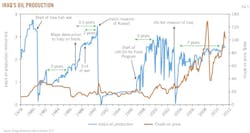

Iraq's varying restoration paces

Iraq's production plunged after the start of the Iraq-Iran war in 1980.

It recovered within few months, but major damage in 1982 reduced production capacity by more than 600,000 b/d. Since that date, it took Iraq 3 years to increase its capacity by about 1 million b/d.

Capacity declined again toward the end of 1986 after several successful Iranian attacks. It took Iraq 31⁄2 years to increase its capacity. From the end of the war in August 1988, it took Iraq 2 years to increase its capacity by about 750,000 b/d.

The experience of other countries tells us that Iraq could have been able to increase its capacity by about 1 million b/d within 3 years, but the invasion of Kuwait stalled that process.

In August 1990, Iraq invaded Kuwait. Iraq's production declined substantially and immediately because of sanctions that prohibited the international community from importing Iraqi oil. Its production stopped completely during the second Gulf war in 1991 and the liberation of Kuwait.

Iraq was under United Nations embargo between 1991 and 2003. It was not able to export oil until the UN Oil-for-Food Program was signed in May 1996 (UN Resolution 986), which allowed Iraq to export oil and buy badly needed spare parts.

The repair of a pump station on the Iraq-Turkey pipeline and the establishment of UN monitoring and aid distribution facilities delayed implementation of the agreement for several months. It took Iraq's production capacity 3 years from the implementation of the agreement to reach sustainable levels (Fig. 5).

The US-led invasion of Iraq on Mar. 20, 2003, halted Iraq's oil production and destroyed parts of Iraq's oil production capacity. It took 7 years from the day of the establishment of transitional government to restore preinvasion production levels.

Several factors contributed to the delay, including the lack of use of technology before the invasion, cannibalism of various fields and wells to increase production in others, old infrastructure, corrosion, and mismanagement of fields for a long period under the Saddam regime. Other factors that are well known to most readers include the delay in adopting a constitution, the lack of petroleum law, spread of violence, and corruption.

Earlier government and company announcements called for an increase in Iraq's production capacity by 9.5 million b/d within 8 years between 2010 and 2017 to reach a total capacity of 12 million b/d. However, experts agree that Iraq cannot increase production by more than 3.5 million b/d at maximum by 2017, suggesting that increases in production capacity take time, even under the best of circumstances.

Looking at Fig. 5, one has to wonder why was Iraq able to restore production in the 1980s and 1990s faster than it did between 2003 and 2010? In the 1990s, Iraq was under a UN embargo and it received only one third of its oil revenues through the Oil-for-Food Program.

Libya and the 3-year rule

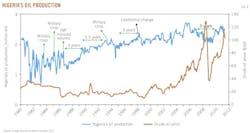

Figs. 1-5 demonstrate that 3 years has become the rule of thumb for capacity increase.

The experiences of Iran, Kuwait, Russia, Nigeria, and Iraq indicate that major capacity increases require political stability along with stable legal and institutional framework.

Where will Libya stand relative to these countries?

To answer this question, we need to ask another: Given the current situation in Libya, which country suffered from similar circumstances?

Is Libya similar to Iran? No, because the change in government in early 1979 did not result in damage to oil facilities.

What about Iran after the start of the Iran-Iraq war in 1980 when oil facilities were damaged? The answer is again no because Iran had a leader, a government, a constitution, and a set of laws. Libya does not enjoy any of these benefits today.

Is Libya similar to Russia? No. Russia did not suffer from damage to its oil facilities after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Is Libya similar to Nigeria? No, because there was not a revolution in Nigeria that ousted the government. In addition, unlike Libya, companies in Nigeria have had a long time of experience restoring production after periods of political instability and violent events.

Is Libya similar to Kuwait? No. The Kuwaiti leadership, government, constitution, and laws remained the same during and after the invasion of Kuwait by Iraq. In addition, unlike the current government in Libya, the Kuwaiti government had at its disposal hundreds of billions of dollars in its own money to spend on production restoration. Kuwait also enjoyed the political support of the whole world with international companies offering their best experts and technologies.

Is Libya similar to Iraq? Many experts believe so, as stated in various media reports. However, differences abound:

1. Unlike the almost land-locked Iraq, Libya is open with more than 1,000 miles of coastline on the Mediterranean.

2. Unlike the market-isolated Iraq, Libya's geographic location makes it near its main markets in Europe.

3. Unlike Iraq, there are no visible invaders and no official occupation in Libya.

4. Unlike Iraq after the invasion, Libya has a transitional government.

5. Unlike Iraq, new technology has been used in recent years in Libya.

6. Unlike Iraq, there is no sectarian violence in Libya. Almost all the population is Sunni Muslim. There are some tribal issues, but they are not as severe as the sectarian divide in Iraq.

Other Libyan factors

It is worth noting that the experience of the IOCs around the world indicates that they can work in locations plagued with violence, but they have no interest in investing in areas that do not have a clear and stable legal regime.

While violence in Libya remains the headline news, IOCs are more interested in the formation of a new legitimate government, new constitution, and new laws that govern investment in this oil-rich country.

Land mines remain a serious problem in the Libyan desert, not only those that were planted during recent events but also those that remain under the sand dunes from World War II.

In the short run, Libya can increase production to more than 500,000 b/d within a few months, contingent on the return of expatriates to the oil fields. The inability of the National Transitional Council to repair the pump stations in the last 5 months that were bombed by Qaddafi loyalists should not be used as evidence that it will take time for exports to start. The delay was related to the fact that all expatriate engineers and workers left Libya. It is expected that the situation will change upon their return.

However, one issue might affect the speed of recovery of oil production in Libya: looting. People did not realize the impact of looting in Iraq until the IOCs went in. This explains part of the delays in ramping up Iraq's oil production, and the same is expected in Libya. Nevertheless, given the experience of various countries, land mines, looting, and corrosion will cause delays in bringing further production online.

While it is difficult to compare the experience of any of these countries in capacity building to that of Libya, their experiences set parameters that help place Libya relative to them. Based on the argument above, the book ends are clear: Libya will not be like Kuwait and will not be like Iraq. As we saw in the figures, it took Kuwait 21⁄2 years to restore its pre-invasion production, while it took Iraq more than 7 years.

Fig. 6 shows Libya's oil production since 1974 with a projection of production recovery based on the discussion above. It shows that, based on various factors, it is expected take 3-31⁄2 years for production capacity to be restored to precrisis levels.

In conclusion, the experience of the various countries and the situation in Libya today show that the experience of Libya will not be like that of Kuwait; therefore, it needs more than 21⁄2 years to restore production. It also shows that it will not be like that of Iraq; therefore it will take less than 7 years to restore production.

Like most other countries, it will take 3-4 years to restore production in Libya to precrisis production levels.

Acknowledgment

The author thanks Juan Pablo Perez Castillo, Hussein Ebn Yusef, Wumi Iledare, and Jim Williams for useful comments and insights.

The authorMore Oil & Gas Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com