Saudi Arabia, UAE promote energy from sun and wind

It would seem unlikely that the Persian Gulf region, so commercially dependent on fossil fuel production and exportation, would lead the world’s search for the 21st Century’s energy source. However, the Gulf Cooperative Council (GCC) nations—Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE—are planning a multitude of projects to exploit the region’s seemingly limitless sun and wind and to pioneer efforts to limit their fossil fuel dependence.

The UAE, particularly Abu Dhabi, leads the race to strategically develop sustainable renewable energy sources—with Saudi Arabia close behind.

At the November 2007 Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries summit in Riyadh, where one of the core strategies was clean technology development, the Persian Gulf members of OPEC pledged to devote $750 million to study the viability of clean energy, with a particular focus on carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology. Some incredulous detractors questioned their sincerity, as most of the money was earmarked for CCS, which is designed primarily to extend the viability of hydrocarbon use.1 However, OPEC and the GCC nations understand that fossil fuels are an exhaustible resource. They also recognize that they can utilize their prodigious amounts of sun and wind power to transition to next-generation renewable technology for both domestic use and for exporting to Europe.

City of the future

While other GCC nations have started the race to green technology, Abu Dhabi has quickly moved ahead. Although Saudi Arabia has made early strides in the study of solar power, and Qatar is studying the benefits of wind energy, the next generation of GCC green energy is solidly in the UAE.

Saudi Arabia, one of the first to initiate renewable energy pilot projects in the 1980s, seemed to have rapidly lost its desire as oil prices regained their stability in the late 1980s.

Abu Dhabi intends to build upon the technological progress made since then in economies of scale to catapult itself to the head of an alternative energy boom.

Abu Dhabi, which traditionally is a less-traveled destination in the UAE and much less glitzy than its sister emirate, Dubai, caused predictable mirth in the energy community in 2006 when it announced a $22 billion, comprehensive, clean energy plan called the Masdar (“Source”) Initiative.

The Masdar Initiative has six logistical components that will function as catalysts to commercially reinvent Abu Dhabi and—by extension—the wider UAE.

When unified, the Masdar Initiative will transform the UAE’s energy consumption patterns.

The initiative’s six components are construction of the world’s first carbon-neutral municipality, Masdar City, and further development of the Masdar Institute of Science and Technology (MIST), the Masdar Research Network, the Innovation and Investment unit, the Carbon Management unit, and the Special Projects unit.

Abu Dhabi hopes the academic and corporate partnership, as exemplified by MIST, will soon enable the exportation of high-grade renewable energy technology.

However, the Masdar Initiative branches that receive the lion’s share of attention and funding are Masdar City and the carbon business unit.

Masdar City is designated as a near-zero waste, zero carbon, and automobile-free city to be located in the expansive desert at the edge of Abu Dhabi. Housing about 50,000 inhabitants alongside 1,500 anticipated businesses, it carries a price tag of $22 billion and will take about 8 years to build. Fig. 1 is an artist’s rendition of the future city.

Plans for Masdar City, which will use only renewable energy resources, would eliminate 99% of the waste stream.2 Planners anticipate solar energy as the principal fuel source and foresee residents traveling in magnetic trains that crisscross the city.

However, Masdar City does not lack its chorus of critics as the UAE allegedly has the world’s largest carbon emissions per capita. Detractors argue that Masdar City will merely be a showcase city without any substantive work to realign the energy industry.3

Because the UAE sometimes experiences crippling power outages due to its rapid population growth and shortage of gas, others argue that the drive for sustainable energy arises from its own domestic needs, rather than global environmental concerns.4 Masdar’s carbon business unit is tasked with the triple mandates of setting up carbon emissions trading, taking advantage of the Kyoto protocol’s Clean Development Mechanism program, and developing marketable CCS technology. Hydrogen Energy International Ltd., a joint venture of British Petroleum and Rio Tinto, will develop Masdar’s CCS project, which will cost $3 billion and is expected to start operations during the first quarter of 2013.5

The initial capture will be 2 million tonnes/year of carbon dioxide to be used for enhanced oil recovery. Every tonne of CO2 injected would lead to an extra 2.5-3 bbl of oil recovery.5 The CO2 will be captured from heavy-carbon-emitting industries across the UAE, with an aim to monetize it in the form of carbon credits in an eventual regional carbon market set up in the next several years.6

Oil producing countries are studying CCS technology because they feel it will show that fossil fuels will be viable for many more decades, Kyoto Protocol notwithstanding.

Furthermore, if pumped into aging oil fields, captured carbon could supplant valuable, exportable natural gas in its role of increasing oil field pressure.

Not only does Abu Dhabi aspire to have Masdar be the largest CCS user in the world, it intends to leverage its expertise with financial investment in the global drive for clean energy. The Masdar Clean Tech fund has a $250 million starting investment budget to develop a wide-ranging portfolio in alternative energy development internationally.7

The government of Abu Dhabi, through Abu Dhabi Future Energy, has put $100 million into the clean tech fund, while Credit Suisse and the Consensus Business Group have put in $100 million and $50 million, respectively.7

Hydrogen power plant

The Abu Dhabi Masdar Initiative is more advanced by far than its neighbors’ clean energy activities. In 2008, Masdar executives announced an ambitious deal with Hydrogen Energy to build one of the world’s first commercial hydrogen power plants, which would cost about $2 billion and would have a generation capacity of about 420 Mw.8

The hydrogen plant will capitalize on two emerging technologies—hydrogen manufacture and carbon sequestration.9 The objective is to produce hydrogen via steam reforming of natural gas. The resultant CO2 can be used to increase pressure in mature oil fields or can be simply stored underground.

The planned hydrogen plant, along with the planned construction of a 100 Mw concentrated solar plant in Medina Zeyad, will add to the UAE’s current power generation capacity of 16,670 Mw.10

Abu Dhabi hopes that its initial investments will be catalysts for international investment when investors recognize renewable energy’s potential profitability. Abu Dhabi’s objective, of course, is to maintain global energy primacy. Where it now exports oil and gas, it desires to soon export advanced renewable energy technology, coupled with renewable power through an intraregional electrical network, such as the pan-GCC power grid.

Saudi solar strides

Saudi Arabia has taken initial steps to create a solar industry to eventually service a portion of its domestic energy demand.

Sheikh Ahmed Zaki Yamani, the influential former Saudi Minister of petroleum and mineral resources once explained the Kingdom’s interest in renewable energy by saying, “The oil won’t last forever.”11

Saudi Arabia is located in the heart of one of the world’s most productive solar regions. This region is a large, rain-free area that stretches from Morocco to the eastern edge of Central Asia and receives the most potent kind of sunlight.

Saudi Arabia developed some of the first renewable energy projects in the Middle East as early as the late 1970s and early 1980s. In 1977, the Saudi Arabian National Center for Science and Technology and the US Department of Energy, as part of a joint cooperation agreement, developed the Saudi Solar Village project, which supplied a village 20 miles outside of Riyadh with consistent electricity.12 While the project was pronounced a success, not much such activity has since occurred.

However, that may soon change.

EU-MENA Supergrid

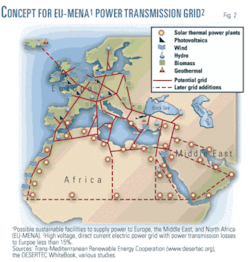

The Middle East-North Africa (MENA) region is gaining new attention, partly because the European Union is considering a transcontinental super energy grid that would harvest the sun’s power for export to Europe (Fig. 2).

The Trans-Mediterranean Renewable Energy Cooperation (TREC) is the concept of a consortium led by the Club of Rome, senior members of the German Aerospace Bureau, and several universities in Europe and the Middle East.

TREC is integral to a political initiative that will build a super-grid that spans the MENA region but focuses on Saudi Arabia’s being the solar powerhouse. TREC is to be powered by concentrated solar thermal power (CSTP) plants and wind turbines, with the electricity to be carried by high-voltage, direct current, long distance power transmission lines to Europe, while powering seawater desalination plants in MENA (Fig. 2).

TREC’s primary goals are to develop clean energy that minimizes the carbon imprint of the EU and MENA and to reduce the EU’s dependence on Russian natural gas.

One notable difference between the current solar power concepts and the projects dating from the 1980s is that the massive projects of today are intended to provide considerable amounts of electricity to national and even transnational energy grids.

Earlier projects were more concerned with the decentralization of power needed for such goals as providing rural villages with stand-alone power generation units, primarily because it was uneconomical to provide power from the centralized grids to such remote areas.

CSTP offers the best economies of scale for large, low-cost solar power production.13 A recent study, based on satellite images by the German Aerospace Center, illustrates that using less than 0.3% of the vast desert area in MENA for CSTP would produce adequate electricity and desalinated water for both the EU and MENA regions.14 CSTP plants generally are ideal for producing secure solar power.

It is estimated that every year sunlight representing the potential for generating 630,000 Tw-hr of power falls unused on the deserts of the MENA states.15 To place it in perspective, Europe uses 4,000 Tw-hr/year of energy—0.6% of the unused solar energy falling in the MENA deserts.15

CSTP technology

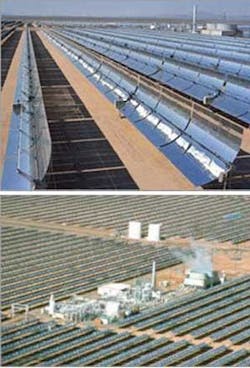

The basic technology that undergirds CSTP is elementary: CSTP plants use curved mirrors called “parabolic trough collectors” that concentrate sunlight to create heat, which generates steam to drive steam turbines that, in turn, generate electricity (see photo of California CSTP model).15

Heat storage tanks, such as molten salt storage areas, can be used to store heat during the day to run the steam turbines at night. The plan has a clear preference for CSTP over photovoltaics because CSTP can supply electricity for periods up to 24 hr. And CSTP is a proven technology that has provided electricity in Nevada and California since the 1980s.16

The TREC plan, which requires initial state support to reach the goal of producing a capacity of 100 Gw of exportable solar power by 2050, has gathered some high-profile endorsements. These include Jordan’s Prince Al Hassan, French President Nicolas Sarkozy, and UK Prime Minister Gordon Brown. Sarkozy’s support for the multinational grid is consistent with his goal to create a more robust Mediterranean bloc of nations. A MENA-EU energy grid would serve as a first step for such an interconnected bloc.17

Even though the plan for a transnational solar grid has not developed beyond the conceptual stage, there are certain pressures, such as the energy shortages and the finite quantity of petroleum, that drive the concerned parties towards this potent energy source, with Saudi Arabia taking the first steps in that direction. European and MENA leaders envision such a super grid as an optimal solution that serves both Europe and the Middle East: It would address Europe’s energy needs and MENA’s massive desalination requirements.

Saudi Arabia’s role

After the pilot schemes to develop solar energy in the 1980s, Saudi Arabia is taking a much more active approach to solar power development.

In March 2008, Saudi Arabia’s oil minister, Ali al-Naimi, stated that Saudi Arabia’s strategic plan is to sharpen its solar energy expertise, essentially modeling it on the expertise that Saudi Arabia enjoys in the oil industry. Al-Naimi advised the French Newsletter Petrostrategies: “One of the research efforts that we are going to undertake is to see how we make Saudi Arabia a center for solar energy research, and hopefully over the next 30-50 years, we will be a major megawatt exporter.”18

Echoing the official view, Al-Naimi explained that solar energy was the cleanest of renewable energy and that its usage should expand to all parts of the world and all economic sectors, particularly those involving manufacturing and power generation.19

Despite these declarations, CSTP is still not competitive with conventionally generated energy. Consistent with Saudi statements, however, experts estimate that by 2020, solar thermal-produced power will be competitive with traditional fossil fuels.20

The enhanced use of solar power should, logically, contribute to price stability in the solar energy markets, as the sun’s power is unlimited and quite stable in the cloudless desert. However, most experts estimate that it will take at least another decade to bring the cost down to 9-11¢/kw-hr, buttressed by well-sited plants and large economies of scale.21

Yet many argue that the West is just expressing wishful thinking when it contends that weaning itself off of fossil fuels will lead to energy security. If energy dynamics evolve along the present trajectory, the same geopolitical factors that pervaded the Oil Age may very well persist in the Renewable Energy Age, if one region remains the dominant producer.

Oil, gas primary

However impressive these renewable energy projects are to the development of power generation in Saudi Arabia and Masdar City in Abu Dhabi, it is anticipated that oil and gas will remain the primary fuels for the world’s vehicles and manufacturing facilities for the foreseeable future.

It is understandable that the GCC countries wish to increase oil and gas supplies for export and to reserve renewables for domestic usage. But the GCC preference for renewable energies is also the result of certain market inefficiencies; for example, the previously mentioned GCC gas crises and power outages that result from artificially low administrative prices in GCC markets.

Renewables also could serve as an energy source to satisfy the peak generation needs of the rapidly industrializing Gulf countries.

Yousef Omair Ben Yousef, CEO of Abu Dhabi National Oil Co., represented the pervasive governmental view when he stated that he saw neither conflict nor rivalry between renewables and oil and gas. When asked, he declared: “I don’t see Masdar as a competitor or an alternative…there is room for both.”22

Illustrating the Saudi response to the economic crisis, Saudi King Abdullah—at the emergency economic summit held in Washington, DC, on Nov. 15, 2008—pledged to invest more than $400 billion in the strategic Saudi industrial sectors, with the bulk going to oil field development.23 That sums up the strategic view for the region: to be the flagship in the movement towards a future of renewables while simultaneously hedging its bets in the current Oil Age.

References

- Mufson, Steven, “OPEC to Put $750 Million Toward Climate Research,” Washington Post, Nov. 19, 2007.

- “Work Starts on Gulf ‘Green City,’” BBC News, Feb. 10, 2008.

- Landais, Emmanuelle, “UAE tops world on per capita carbon footprint,” Gulf News, Oct. 30, 2008.

- Dargin, Justin, “Trouble in Paradise—The Widening Gulf Gas Deficit,” Middle East Economic Survey, Sept. 29, 2008.

- “Abu Dhabi’s $3b Carbon Capture Project Set for 2013,” UAE Interact, Oct. 29, 2008.

- Dargin, Justin, “A Carbon Market for the Gulf,” Nuova Energia, Oct. 16, 2008.

- Kanellos, Michael, “New Player in Clean Tech,” CNet News, May 14, 2007.

- “Hydrogen Energy Plan Clean Energy Plant in Abu Dhabi,” British Petroleum web site, Jan. 21, 2008.

- “Abu Dhabi Plots Hydrogen Future,” BBC News, Jan. 21, 2008.

- “UAE plans to increase power generation by 60% by 2010,” Kuwait Times, Mar. 25, 2007.

- “Saudi Arabia and Solar Energy,” Saudi Aramco Journal, Vol. 32, No. 5, Sept.-Oct. 1981.

- Miller, Judith, “In Saudi Arabia the sun shines bright on solar power,” The New York Times, Nov. 1, 1983.

- For information on how concentrating solar thermal power technologies compare financially with one another, see “Overview Of Solar Thermal Technologies,” p. 3, (http://www.energylan.sandia.gov/sunlab/PDFs/solar_overview.pdf). For information about how CSTP technologies compare financially with other renewable energy electricity technologies, see “Project Financial Evaluation,” p. 3, (http://www.energylan.sandia.gov/sunlab/PDFs/financials.pdf).

- “TRANS-CSTP Trans-Mediterranean interconnection for Concentrating Solar Power,” Institute fur Technische Thermodynamik, (http://www.dlr.de/tt/desktopdefault.aspx/tabid-2885/4422_read-6588/).

- Lubbadeh, Jens, “Harnessing the Saharan Sun: Is Desert Solar Power the Solution to Europe’s Energy Crisis?” Spiegel Online International, Apr. 30, 2008.

- “Solar Energy Technology Program: Concentrating Solar Power,” US Department of Energy, (http://www1.eere.energy.gov/solar/csp.html).

- “EU Leaders Show Muted Enthusiasm for Club Med Plans,” Spiegel Online International, Mar. 14, 2008.

- “Saudis Planning to Invest in Solar Energy,” Asia News, Apr. 3, 2008.

- Boselli, Muriel, “Saudi Oil Minister Slams Biofuels, Favors Solar Energy,” Reuters, Apr. 10, 2008.

- Supra note 19, “Harnessing the Saharan Sun: Is Desert Solar Power the Solution to Europe’s Energy Crisis?

- Burgermeister, Jane, “Low-Cost Solar Thermal Plants at Heart of Algerian-German Research Push,” Renewable Energy World, Mar. 20, 2008.

- Walsh, Bryan, “Renewable Energy: Desert Dreams, Time Magazine, Feb. 13, 2008.

- “Saudi King: $400 Billion Investment in Oil Sector,” Associated Press, Nov. 15, 2008.

The author

Justin Dargin ([email protected]) is a research fellow at the Dubai Initiative at Harvard University, where he researches energy policy in the Persian (Arabian) Gulf region. He specializes in carbon trading, oil and gas production in the gulf, and the legal framework surrounding the gulf energy sector. During his graduate legal studies, he interned in the legal department at OPEC. Dargin also was a research fellow at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies specializing in the GCC natural gas industry. He is writing a book related to the Persian Gulf energy industry. He is fluent in Spanish, English, and Arabic.