Mexico's CRE issues new gas quality specs

Mexico's Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE) has completed the fifth-year review of gas-quality specifications in Mexico.

New specs became mandatory in the second quarter of this year, mainly in response to several complex factors:

The new Mexican gas code (Norma Oficial Mexicana, NOM-001-SECRE-2003, "Calidad del Gas Natural," or NOM) introduces gas interchangeability parameters relying on the Wobbe Index and fixes several trace elements in a new way.

This NOM also solves various gas-composition issues:

CO2 (imported from South Texas pipelines connected along the border with Mexican pipelines).

Ethane (a vexing problem associated with the lack of petrochemical infrastructure in Mexico).

The complexity of these concurrent factors and how they can be managed by importers, producers, and consumers present significant issues for the availability, reliability, and quality of natural gas in Mexico.

Production mix; imports

In the Bay of Campeche, for example, a multinational consortium provides more than 1 bcfd of nitrogen to Pemex for injection into oil wells to maintain formation pressure. This process will likely raise to 5% the nitrogen content of gas produced in that region affecting southern and central Mexico.

At the same time, an estimated 1 bcfd of gas could flow from the US into Mexico via pipeline for the next 5 years, the likely sources being south and West Texas.

CO2 cannot be totally eliminated from these sources given the characteristics of US pipelines moving this gas and the availability of processing infrastructure within border regions.

The Mexican code, therefore, retains the 3% CO2 content level, in line with the relevant US pipeline tariffs.

Additionally, Pemex production in the Burgos basin and eventually in the northeastern portion of the Gulf of Mexico (Tampico-Misantla, Lankahuasa) will require additional cryogenic units and gas conditioning equipment to deal with liquids and other impurities.

On the other hand, LNG moving into Mexico from both the Atlantic and Pacific Basins is likely to be rich in propane and butane (C3+), hence the need to control liquids through a dewpoint limit of –2° C.

Finally, the lack of petrochemical infrastructure in Mexico causes significant amounts of ethane to be reinjected into the National Pipeline System.

Hence, a limit to this element is fixed indirectly through the use of a high calorific value of 1,170 btu/cu ft, which may contribute to the revamping of Mexico's petrochemical sector.

Objectives

The new code regulates gas exclusively as a fuel and accounts for it in energy units.

Base conditions (i.e., 68° F. and 14.22 psig) are only a reference for convenience and consistency with other CRE standards; no significant problem arises if another reference is used.

Yet in-depth analyses looked at the impact of nitrogen (N2) in processes that use gas as a raw material, especially where hydrogen is the main useful component (e.g., steel direct reduction and fertilizers).

The main objectives of the NOM are:

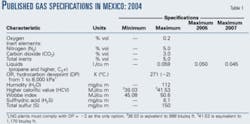

Table 1 shows the new Mexican gas code; Table 2 shows international comparisons.

It is worth noting that high heating value (HHV) maximum and minimum parameters are readily comparable in Mexico and the other referenced countries.

All nations now have similar Wobbe indexes, which effectively provide the basis for gas interchangeability.

Inert elements

Injection of 1 bcfd of nitrogen to maintain formation pressure results in an increase of N2 in Pemex' Cantarell complex. Oil production in this region relies on such large amounts of N2, which mixes with associated gas and goes into processing.

The CRE required an assessment of handling and transportation issues related to natural gas at 5% N2, as well as research into low pressure and high-pressure combustion processes. Since most impacts arising from this situation, the diluting effect of N2, that is, are in Pemex subsidiaries, the national oil company absorbs most of the costs and operational responsibility, while guaranteeing higher than 950 btu/cu ft for delivered gas

In addition, Pemex is required under the NOM to install a nitrogen-removal unit in 2005 and cannot overshoot N2 above 5% in the Southeast.

Pemex research into N2 shows no significant increase of NOx from gas-fired power plants (but adjustment in combustion systems may be necessary to maintain heat conditions), nor damages to turbine elements.

This is consistent with 5% limit on N2 specified by turbine manufacturers such as Solar, GE, Siemens, and Westinghouse.

This limit does point to an increase between 1% and 3% of gas volume required for the same amount of energy, which means adjustment of compression units and more pipeline capacity used, as well as calibration of end-user equipment.

There are offsetting elements in the NOM, however, such as C3+ and ethane, which need careful assessment before the final production and processing schedules are decided.

While CO2 is kept at a maximum of 3% as in the previous NOM, total inert elements cannot exceed 5%.

This means that if Pemex hits the maximum N2 level of 5% in the Southeast region, no CO2 can be present in that mix.

On the other hand, gas flowing in US-Mexico interconnected pipelines cannot exceed 3% CO2; this would then only allow 2% N2 for total inert elements to remain at 5%, which should not pose any special problem to those pipelines.

Dewpoint; hydrocarbon liquids

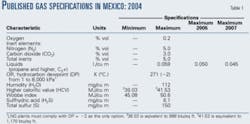

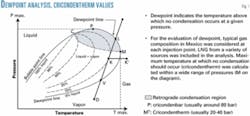

The NOM addresses hydrocarbon condensation situations through a minimum dewpoint set at –2° C. (Fig. 1). This will prevent most condensation problems in pipeline systems at given pressure and temperature conditions (Figs. 2a and 2b).

Most sources of domestic and imported gas in Mexico can meet this standard, including LNG from both the Atlantic and Pacific basins, although further liquids removal may be necessary depending on sourcing and commingling gas.

In the case of LNG terminals built in Mexico, the new dewpoint standard is mandatory. In turn, domestic gas may comply with either of two specifications: the abovementioned dewpoint or a specific limit of 0.059 l./cu m. As this value will go down to 0.050 in 2005 and 0.045 in 2007, however, Pemex must improve process control and commission new cryogenic units; two of these are now operating in the Northeast.

Relative to cooling points and the inherent condensation of the gas (i.e., Joule-Thomson effect), it is estimated that they will be between 0.5° C./bar to 1° C./bar at pressure reduction points.

While delivered-gas temperature is set at 10° to 50° C., this means there is a safety margin of 12° C. for natural gas moved in a pressure range of 1,200 psig to 350 psig, which satisfactorily protects transmission systems and LDC city gates in Mexico.

Interchangeability; Wobbe Index

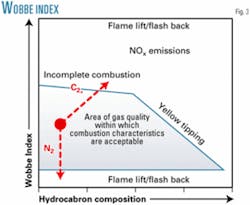

According to ISO-13686, gas interchangeability indicates the degree of substitutability between the combustion characteristics of different gas types.

Gas with one particular composition is interchangeable with another having a different composition, only if the quality of combustion remains within the specified range.

The Mexican NOM uses the Wobbe Index to deal with gas interchangeability. This index shows the relationship between heat value and the specific gravity of gas, as a flow of energy at constant pressure.

Gas with different compositions but the same Wobbe Index provides the same amount of energy at the same pressure (Fig. 3).

This relationship is represented by a flow equation at the flow point, as follows: W=HHV/ (squareroot of)sg ; where W= Wobbe Index; HHV=high heat value; and sg=specific gravity.

Ethane

Customarily ethane is reinjected into the NPS in Mexico. While there are relative pricing issues explaining this highly anomalous situation, the lack of petrochemical infrastructure is a fundamental factor.

At the request of the Mexican Energy Ministry, CRE tackled the problem within the strict limits of the NOM.

In other words, a NOM, a code or standard, cannot be used as a pricing tool nor as a means to solve industrial promotion problems inherent in energy policy.

Gas interchangeability and the Wobbe Index allow fixing the high calorific value of natural gas at 41.53 MJ/cu m.

Other things being equal, an indirect limitation to ethane is the result.

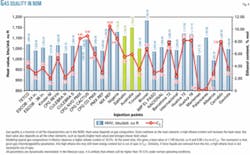

For example, with typical gas compositions in Mexico and considering the relationship among methane, ethane, nitrogen, carbon dioxide, and liquids, the set high calorific value, and the Wobbe Index, the results shown in Fig. 4 are obtained.

An indirect restriction to ethane in pipeline quality gas (most likely between 10% and 12%) makes it necessary for Pemex to free up more of this raw material to the petrochemical industry.

Given the flexibility allowed by interchangeability parameters, however, it remains to be seen how the final mix is set at the processing facilities, for excess ethane may be manageable under high nitrogen content but be out of specification if fewer liquids are removed.

In one case, the diluting effect of N2 may allow for the higher heating value of ethane, but in the other natural gas would overshoot the high calorific value limit with an excess of several "hot" components.

A little ethane is probably good and the NOM does its job in restraining it.

Nonetheless, ethane availability, relative pricing between natural gas and ethane, and the promotion of the petrochemical sector, are likely to remain key issues in Mexican energy policy.

The authors

Raúl Monteforte (rmontefo@ cre.gob.mx) has been a commissioner in Mexico's Energy Regulatory Commission since 1996 and was reappointed by the president of Mexico for a second term, until 2006. He is directly responsible for natural gas transmission projects in Mexico, including open-access systems, crossborder interconnections, industrial park energy projects, self-consumption groups, and cogeneration in integrated energy projects. He has also directed and managed the CRE permitting process for the National Pipeline Network. At present, he coordinates regulatory work for the 5-year review of Mexican pipelines and several LDCs in Mexico. For the last 4 years, Monteforte has chaired the National Committee of Technical Standards for the natural gas industry. He holds a BA (1982) in social and political sciences from the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), an MS (1984) in energy studies from the Science Policy Research Unit of the University of Sussex, UK, and a PhD (1989) in development economics from the Institute of Development Studies of the University of Sussex.

Luz María Damián has been a chief advisor at the CRE since 2001. A leading gas system modeler at the CRE, she has had significant participation in the elaboration and enforcement of Mexican gas standards (technical and safety related), as applied to pipelines and distribution systems. She has been at the CRE as a technical expert in the gas industry since 1995 and previously worked as a full-time researcher at the Institute of Mexican Petroleum. Damián is a chemical engineer from the National Polytechnic Institute of Mexico.

Marco Antonio Espinal has been a technical director in the CRE gas directorate since 2001 where he focuses on engineering evaluation of gas pipeline and distribution projects and participates in managing the regulatory process of the Mexican gas codes and auditing companies. Espinal is a chemical and oil engineer from the National Polytechnic Institute of Mexico.