ANWR 1002 Area and development: one question, many issues

In 1999, a young master's degree candidate in photo-journalism, John Dunne, spent the summer in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge of Alaska, taking pictures and keeping a journal of his experiences.

On May 19, after arriving in the small Inupiat village of Kaktovik, along the northern coast of ANWR, he waited for the weather to break and his pilot to arrive (all movement in and out of the refuge is by small plane).

A week later, he made this entry: "May 26. Standing by the beautifully warm fuel heater in the trailer as I write. I got it running yesterday for the first time. Hadn't bothered before. I figured I'd better get used to the weather. But at ten below, heat feels good."1

null

Thus, in a nutshell, are the ironies that are so prevalent in the continuing debate over this area. Eight-to-nine months of the year, the coastal plain portion of ANWR—known as the 1002 ("ten-o-two") Area, where the majority of oil prospects lie—is sheathed in ice, snow, and subzero winds. It is not scenic (in the normal sense) or hospitable (in any sense), especially to humans.

Animal life shrinks to small clusters of muskoxen, huddled along sheltered, grass-patched river valleys, and possibly a few polar bears, who may wander this far south from their normal range offshore on the pack ice.

The coastal plain, however, is inviting to energy companies, at any time of the year—for it holds beneath its frozen surface estimated billions of barrels of recoverable oil. The very same oil, one might reflect, that powers Mr. Dunne's "beautifully warm fuel heater," as well as the airplane that brought him to ANWR and returned him safely home again.

Much of the public, and perhaps all of the domestic US energy industry, are aware of the debate today, at least in general terms. Claimed as the "American Serengeti" on the one hand, the 1002 Area is said to be "America's last great oil frontier" on the other. But what are the actual facts, the main arguments, that support each side?

In truth, these are not really difficult to sort out, provided one hasn't already sworn allegiance to a position. Yet it is unlikely that facts alone will carry the day.

The debate, after all, is not a simple matter of "oil vs. animals." It represents instead a long-standing conflict with deep political, institutional, intellectual, and symbolic elements, all touched by inevitable scientific uncertainty. Facts there certainly are—but other realities color and shape the landscape of discussion at least as much.

Background and legislative history

Early years

Debate over whether to withdraw a large portion of northeast Alaska from any and all development has continued for half a century.

Beginning in the 1950s, a group of bio-scientists that included Lowell Sumner, Olaus and Margaret Murie, and George Collins, then head of the US Fish & Wildlife Service (FWS), with the support of Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, launched a grassroots campaign to gain protection for the area—mainly from mining, then the form of resource development most common in Alaska.

Arguments pro and con were colored by Alaska's political position at the brink of statehood. In the fall of 1960, barely 8 months after statehood was achieved, the House of Representatives passed legislation in favor of establishing an "Arctic Wildlife Range."

Led by newly elected Alaskan Sens. Bartlett and Gruening, the Senate blocked final passage of the bill. The deadlock was broken by President Eisenhower, who directed his Sec. of the Interior, Fred Seaton, to establish the Range by executive proclamation.

Issued on Dec. 6, 1960, Public Land Order 2214 designated an area 8.9 million acres in extent, including most of the northern half of the current refuge, which it officially dubbed the "Arctic National Wildlife Range."

This legislation spelled out, in its first paragraph, the purpose "of preserving unique wildlife, wilderness and recreational values" and turned over jurisdiction of the Range to the US FWS. Using the term "range" reflected the fact that the area was not final designated wilderness: In essence, this decision had been put off. Future debate, in a sense, was assured.

The 1970s and 80s

During the next decade, the context of discussion changed radically.

Discovery of giant oil reserves at Prudhoe Bay (1968) and the Arab Embargo of 1973 placed North Slope development high on the list of national priorities. Following several years of ardent debate, with much back-and-forth legislation proposed, Congress passed the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA, Public Law 96-487), which Pres. Carter signed into law in early 1980.

This act, which set the stage for controversy down to the present, was a type of grand compromise. On the one hand, it more than doubled the total set-aside area to 19.6 million acres, conferred upon it the new title "Refuge," and officially designated 18.1 million acres of it as "wilderness," thereby off-limits to all future development.

Yet ANILCA also mandated that the 1.5 million acres of coastal plain be kept off the "wilderness" menu and instead evaluated in terms of both wildlife and petroleum resources. Sec. 1002 of the Act provided for "a comprehensive and continuing inventory and assessment of the fish and wildlife resources of the coastal plainU; an analysis of the impacts of oil and gas exploration, development, and production, and [the ability to] authorize exploratory activityUin a manner that avoids significant adverse effects on the fish and wildlife and other resources."

As prescribed, the US Department of the Interior conducted detailed evaluations, with oil assessment by the US Geological Survey. Seismic surveys over the 1002 Area (1,400 line-miles total) were contracted out to various companies in 1984-85, providing an essential database.

Information from biological, ecological, and geoscientific work was combined into a Legislative Environmental Impact Statement (LEIS), which also included the Secretary of the Interior's recommendations to Congress.

Submitted to Congress in 1987, this report advised three main points:

1.That the 1002 Area contained "outstanding wilderness values."

2.That oil development would result in "widespread, long-term change in habitat availability or quality" for a number of species.

3.That leasing and development should proceed, at full-scale, with efforts made to minimize any adverse impacts.

Late 1980s to present

Congress did not act on these recommendations.

Low oil prices in the late 1980s, peak production from Prudhoe Bay, and the Exxon Valdez oil spill of 1989 together helped quell some of the ardor for opening the 1002 Area.

In 1995, as part of its initial balanced budget legislation, Congress finally moved to allow drilling, but Pres. Clinton vetoed the bill. Clinton's Secretary of the Interior, Bruce Babbitt, did approve drilling in Alaska's National Petroleum Reserve (NPRA), to the west of Prudhoe Bay, a move that has been commonly interpreted as an attempt to distract attention from ANWR.

In the meantime, however, new drilling around the margins of the 1002 Area, as well as new technology to reprocess and better interpret vintage seismic data, led to upward revisions of estimated oil recovery.

New geologic studies performed by the American Association of Petroleum Geologists4 and the USGS in 1995 and 1998 raised the estimated maximum in-place resource from 29.4 billion bbl of oil mentioned in the LEIS5 to 49.5 billion bbl4 and then to 31.5 billion bbl.6 These updated estimates suggested that a significantly greater volume of oil could be economically recovered than previously believed.

A new stage of the debate began with the Bush administration in 2000.

Several factors—including the president's plan to increase domestic production, growing uncertainty and price volatility in the global energy market, and declining production from the North Slope (peak year: 1988)—have combined to place the 1002 Area back in the spotlight, rendering it once again the topic of much controversy.

During the past 2 years, the issue has been brought before Congress repeatedly, with heated debate and no final result.

In terms of political maneuvering, the controversy at present in Congress is largely a rehearsal of legislative scuffles that occurred during the mid-1990s, the late 1980s, and the late 1970s. ANWR is again, perhaps even more than before, a lightning-rod issue for larger power struggles in a narrowly "divided household."

Yet there is new urgency, too. Because of its large potential reserves—larger now than in previous estimates —and because of the deeply problematic situations in the Persian Gulf and in Venezuela, the 1002 Area must figure prominently in attempts today to frame a comprehensive energy policy for the US.

Moreover, there is the situation of Alaska to consider. Foremost among proponents for development, after all, are both senators of the Alaskan delegation, Ted Stevens and Frank Murkowski, who view the area as a crucial economic resource in an era of growing hardship and declining oil revenues.

Institutional level

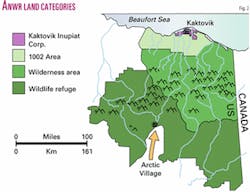

It is essential to point out that all controversy since 1980 has really been about the 1002 Area, the coastal plain portion of the refuge.

The debate, in other words, is not about ANWR per se. The continued use of phrases like "the ANWR debate" and "should we open ANWR to drilling?," however common in discussions and media reports, actually misrepresents the subject.

The great majority of land within the refuge—18.1 million acres, or 92.2% of the total—is now firmly off-limits to any development and seems likely to remain so in perpetuity. This being said, the 1002 Area is where nearly all oil prospects are concentrated and where the greatest concentration of wildlife, at certain times of the year, and apparent vulnerability to impacts, occur.

These facts, along with the brief background sketch given above, indicate that the controversy has involved important institutional and legal questions.

One of these has to do with corporate access to public lands for resource development in the name of the public welfare. In truth, the 1002 Area stands as an important lightning-rod in this long-term struggle.

During the past two decades, an increasing amount of federal land has been withdrawn from oil and gas development. The Clinton administration's designation of new national monuments, plus additions to those already existing, represents the most publicized aspect of this trend.

Such withdrawal has also taken place on a more local basis in many parts of the western US especially, both offshore and onshore. In an era of increasing energy demand and international instability among major energy states, this type of action on the domestic scene must be understood as problematic, sure to set the scene for legislative resistance and reversal.

A second and related aspect of the debate, not often discussed, is that of states' rights. To what degree is the federal government justified in withdrawing from all future consideration a resource of great value that would significantly aid the local economy?

This issue has remained prominent ever since passage in 1958 of the Alaska Statehood Act, which, under Sec. 28, mandated a 90/10 (federal/state) split between the state and federal governments for all royalty revenues collected from development in Alaska. 7

Recent proposals have argued that this be amended to a 50-50 division in the case of the 1002 Area, but until any decision is made regarding leasing, these will remain moot. Overall, as noted, the resource involved here is so large and the potential benefit to Alaska's economy so significant that a new precedent may be set, should a decision be made.

A third and interesting institutional element is the tug-of-war among scientists. This "struggle for territory" is particularly related to the two types of resource involved, as well as the symbolic and political importance attached to each.

Biological resources, for study and protection, exist at the surface. Petroleum resources, for study and extraction, are present in the subsurface. It is the need for the latter to make use of the former's domain that, in a sense, helps inspire competition and, occasionally, partisanship among and even within government-related bodies contracted to research the area.

Yet there has been significant evolution here. In the 1950s, biologists involved with Northeast Alaska were in uncompromising favor of wilderness designation—no development ever. Yet, in part because Prudhoe Bay has caused no ecological disaster (indeed, the Central Arctic caribou herd has even increased in numbers significantly), many biologists, including those at the US FWS, appear inclined toward compromise, toward using "wildlife resources" as an argument for monitoring and minimizing impacts, not necessarily eliminating their possibility altogether.

Similarly, geoscientists and petroleum engineers have continually sought—at the urging of environmental rules and restrictions, to be sure—to reduce any damage done by seismic surveys, drilling, and production, and to trim down the total "footprint" of development through the use of horizontal drilling and other measures.

null

A crucial point here, with regard to "science," is that neither wildlife biology nor petroleum geoscience is able to provide secure guidance through definitive statements. Uncertainty is endemic to both areas of study.

Moreover, such uncertainty is heightened in this case, due to the limitations on available data. Only one well has ever been drilled in the 1002 Area, while seismic data come from widely spaced 2D surveys (average spacing between dip lines is 3.2 miles; between strike lines, 8.5 miles).

Systematic studies of wildlife resources, on the other hand, are hampered by long-distance migration patterns of certain key species and by their nonhabitation of the area for up to 9 months of the year.

Science in the 1002 Area thus largely remains science-in-the-making. While it provides essential knowledge, it keeps the doors for debate wide open.

Recent scientific reports:

A few comments

Within the past few years, congressional requests for updated information have underwritten three major scientific reports relevant to the 1002 Area, published by government-affiliated organizations. These reports include:

1. A detailed study of the petroleum resource potential in the 1002 Area,4 compiled by geoscientists with the USGS.

2. A collection of research summaries on terrestrial wildlife in the area,8 assembled by scientists with the US FWS, Alaska Department of Fish and Game, USGS, Canadian Wildlife Service, Yukon Department of Renewable Resources, and several other organizations.

3. A study on the cumulative effects of hydrocarbon development along the North Slope,9 performed under the auspices of the National Research Council (NRC), by mostly academic researchers in the fields of environmental science and economics, marine biology, and geology.

These three reports directly reflect the major institutional divisions surrounding the 1002 Area debate. The petroleum resource study (to be summarized in Part 2 of this series), as required, does not include any information on development scenarios or wildlife resources.

The wildlife research summaries (to be covered in Part 3) focus on biological issues and also deal with the potential effects of development and what might be needed to reduce or minimize them.

The NRC report, on the other hand, takes up the third major aspect of the debate—actual impacts in already-developed North Slope areas—and is thus strongly focused on forms of damage ("cumulative environmental effects") and their degree of severity. Of the three studies, the NRC report is the least scientific, being mainly descriptive and, at times, anecdotal in treatment, yet containing information important to the 1002 Area.

While all three reports appear to be of high quality, they provide more reason for continuing the existing debate than resolving it. This is largely because information from each area of study remains unintegrated with that from the others.

At the end of the day, we are still left with "petroleum geology" (the riches beneath), "wildlife biology" (possibly threatened), and "impact prediction" (reasons to worry). The remaining parts of this series will attempt to bring together under one roof essential information from each of these areas.

References

1. Text of John Dunne's journal, with photographs, available on the website for The Wilderness Society (http:// www.wilderness.org.arctic/photo_journey.htm). Accessed Mar. 10, 2003.

2. Online text of the 1960 Public Land Order 2214 and major selections from the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (1980) can be found on the website for the US Fish & Wild- life Service, ANWR site (http://alaska.- fws.gov/nwr/arctic/refinfo.htm). Accessed Mar. 15, 2003.

3. Clough, N.K., Patton, P.C., and Christiansen, A.C., eds., "Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, Alaska, coastal plain resource assessment—Report and recommendation to the Congress of the United States and final legislative environmental impact statement." US Department of Interior, Washington, DC, 1987.

4. Gunn, R.D., American Association of Petroleum Geologists Position Paper on Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, 1991, 5 p.

5. Dolton, G.L., Bird, K.J., and Crovelli, R.A., "Assessment of In-Place Oil and Gas Resources," in Bird, K.J., and Magoon, L.B., eds., "Petroleum Geology of the Northern Part of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, Northeastern Alaska," US Geological Survey Bull. 1778, 1987, pp. 277-298.

6. Bird, K., et al. (ANWR Assessment Team), "The Oil and Gas Resource Potential of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge 1002 Area, Alaska," US Geological Survey, Open-File Report 98-34, 1998.

7. Text of the Alaska Statehood Act can be found online (http://www.lbblawyers.com/stateoc.htm).

8. Douglas, D.C., Reynolds, P.E., and Rhode, E.B., eds., "Arctic Refuge Coastal Plain Terrestrial Wildlife Research Summaries," US Geological Survey Biological Science Report, USGS/BRD/BSR-2002-0001, 2002.

9. National Research Council, "Cumulative Environmental Effects of Oil and Gas Activities on Alaska's North Slope," 2003, available online (http://www.nap.edu/catalog/ 10639.html?onpi_topnews_030403).

The author

Scott L. Montgomery ([email protected]) is a Seattle petroleum consultant and author. He is lead author of the "E&P Notes" series in the AAPG Bulletin. He holds a BA degree in English from Knox College and an MS degree in geological sciences from Cornell University.

About this series

Geologist and writer Scott Montgomery assembled a series of articles aimed at providing OGJ readers with a clear review of the relevant information on the ANWR debate. Part 1 offers a brief summary of background material that helps shed light on the debate's long-term nature. Part 2 discusses the geology relevant to the recent USGS oil assessment of the 1002 Area. Part 3 will seek to present an overview of wildlife and other concerns as discussed in various reports released the past few years. Part 4 includes a summary of the major arguments that support each side in the debate, along with their limitations and difficulties where relevant.