US refining outlook rosier than it seems

Sean DeGon

IHS Downstream Energy Consulting

Houston

The outlook for US refining isn't as bleak as US demand trends and economic headlines suggest, but it also is unlikely soon to return to that Golden Age of refining 2005-07.

Refined-product demand in the US is on a slow and steady decline, but thanks to developments in shale oil and gas in recent years, a remarkable turnaround has occurred in the trend for domestic crude and gas production, resulting in lower costs for US refiners.

The corresponding timing of rapidly increasing demand, changing regulations, and a difficult and costly project environment in Latin America, has led to an outlet for increased production from US refineries, promising better days ahead for US refining.

Brightening outlook

News surrounding US refining has been overwhelmingly negative since the beginning of the recession in 2008. Rising crude oil prices, declining demand, and ever-changing regulations have led to weak margins for refiners, even causing several East Coast refineries to shut down.

Crude oil prices are still high, and US demand has been flat and is unlikely to reach prerecession levels for the foreseeable future.

So, why would the outlook for US refiners be expected to improve?

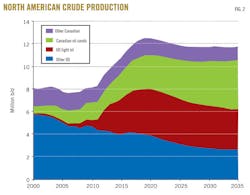

Crude oil production in the US was in long-term decline for many years. Production slid to 5 million b/d in 2008 from nearly 9 million b/d in 1985. With advancements in drilling technology and development of tight-oil plays in the US over the past few years, production has rebounded. Many of these tight-oil plays, such as the Bakken and Eagle Ford, are well known, but additional plays in both the US and Canada are beginning to emerge, many rich in crude oil (Fig. 1).

With these developments, US crude production has steadily increased to nearly 5.7 million b/d in 2011 from its low in 2008 (Fig. 2). A detailed analysis of both the US and Canada indicates large further increases in domestic production in the coming years.

That analysis shows that tight-oil production will reach more than 4 million b/d, bringing total US production to near 1980s levels of more than 8 million b/d by 2020. This production, coupled with another estimated 4.5 million b/d of Canadian crude production by 2022, changes the US crude supply landscape, greatly reducing reliance on imported crude oils.

US shale plays and Canadian oil sands have profoundly affected the US refining industry and promise even greater impact as growth in production continues along with infrastructure to move production to refining centers, such as the US Gulf Coast.

Crude oil prices

The price of dated Brent (light, sweet) crude oil works as the starting point for forecasting the prices of major world crude oils. North Sea crudes now serve primarily European markets but compete directly with the Middle Eastern and African crude oils that serve all major markets, including the US. Prices have shown much more volatility than costs, but a review of historical Brent prices shows a close relationship with costs over time.

Future prices will have to be sufficiently strong to attract large capital investments into key future producing areas. In the Canadian oil sands, for example, high prices will be necessary to maintain a continuing flow of development capital. Tight oil, for all its success, is also a high-cost source of crude supply and requires a relatively high price to develop in most basins.

IHS believes prices will remain at a level sufficient to support ongoing development of conventional and unconventional energy sources, as well as encouraging continued improvement in consumption efficiency. Our price forecast, even at the low point, is high enough to support these developments given our cost outlook. We, therefore, expect continuing development from these unconventional sources.

The increases in North American crude production from unconventional sources will continue to affect the price of crude oil both in the US and abroad. The surge in production will have a deflating effect on world oil prices over the coming years. More directly relevant for US refiners, crude produced from tight-oil plays is light and sweet, while crude from the Canadian oil sands is heavy and sour.

Large amounts of light, sweet crude imports have historically been required by US refiners. These imports generally come from such places as West Africa and the North Sea, requiring long-distance shipping to the US. These crudes also tend to react to political tensions more than do domestic crude oils due to the possibility of supply disruption.

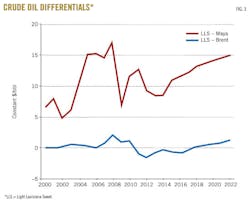

The increase in domestic light, sweet crude production has created an increased source of supply for US refiners with less dependence on world politics and lower shipping costs. As a result, a discount of around $1/bbl in price has developed between domestic light, sweet crude benchmark, Light Louisiana Sweet (LLS), and the traditional import benchmark, Brent, on the US Gulf Coast (Fig. 3). This differential will narrow somewhat as prices gradually decline due to the surge in domestic supplies but will continue until around 2020.

Heavy, sour crudes, such as Maya, which is the heavy crude benchmark on the US Gulf Coast, are discounted to the lighter Brent and LLS crude oils because they require additional processing to produce salable products. The spread between light and heavy crude oil has been wide over the past year due to the surge in Brent prices, but this differential will likely tighten through 2014 with declining heavy crude production, primarily in Mexico, increased heavy crude conversion capacity in the US, and increasing availability of light crude.

From 2014 forward, availability of heavy Canadian crude will increase on the US Gulf Coast with increasing production and the expected completion of several pipeline projects. Brazilian and Venezuelan heavy crude production will also likely increase sufficiently to offset declines in Mexican production by this time. The greater availability of heavy crude after 2014 will increase the differential between light and heavy crude to the $12-15/bbl range over the medium term, in constant dollars.

Natural gas effect

Along with substantial increases in crude oil production from shale plays have come large increases in natural gas production in the US. These production increases have outpaced demand, yielding record high natural gas inventories, which in turn have caused a well-documented plummet in prices. While low natural gas prices are not good for some sectors of the oil and gas industry, such as producers, they are very helpful for refiners.

Many factors affect the margins in a refinery, but the largest component of a refinery's variable operating costs is the fuel used to create energy and to produce hydrogen within the refinery. Demand for both fuel and hydrogen has increased in refineries as demand for ultralow sulfur fuels processing has increased.

The more energy intensive the processes in the refinery, the greater the benefit from low natural gas prices. Cracking and coking refineries that convert the heavy portions of a barrel of crude oil into such light products as gasoline, jet fuel, and diesel are the most energy intensive.

A typical coking refinery is the most energy intensive type of refinery, requiring more than 2.5 times the fuel to process a barrel of crude oil than a typical cracking refinery and will therefore benefit the most from continued low natural gas prices.

Natural gas prices dropped to less than $2/MMbtu for a short period in 2011 from an average of nearly $9/MMbtu in 2008. This drop represents an estimated difference in processing cost of $0.55/bbl for a typical cracking refinery, up to a savings of nearly $1.50/bbl for a typical coking refinery.

In the low-margin environment experienced in recent years, these savings have increased the competitiveness of US high-conversion refineries and likely even saved a few from the fate of refineries in Europe and the Caribbean that pay much higher rates for energy.

While IHS forecasts gas prices to rise slowly from current levels, to the $4/MMbtu range (constant dollar) after 2015, they will remain low in relation to historical domestic gas and oil prices. Prices are also likely to continue to stay low compared with gas and fuel oil prices in many key foreign countries, creating a lasting competitive advantage for US refiners over refiners in other parts of the world, from an operating-cost perspective.

Refinery margins

The US Gulf Coast is the primary refining and pricing center for the North American and Caribbean market. The region accounts for a small portion of US demand but supplies large volumes of products to the East Coast and Midwest via pipelines and shipping, as well as producing most US exports.

US Gulf Coast refinery crude slates have become lighter (higher API gravity) in recent years, causing spare coking capacity and poor conversion margins. IHS's capacity and supply outlook indicates that refiners will continue to seek opportunity crudes in an attempt to maintain profitability over the next several years.

Chief among these opportunities will be expanding pipeline infrastructure to deliver discounted light, sweet crudes to coastal refineries from South Texas and the Midcontinent, as tight-oil production continues to grow.

Despite rather strong margins in 2012, weaker refining margins are likely through the next few years. IHS expects that low-margin environment combined with legislative changes that will affect refiners, such as passenger car and light duty truck fuel-efficiency regulations (CAFE standards) and heating oil switching from high-sulfur fuel oil to ultralow sulfur diesel, will result in some further capacity rationalizations. (CAFE = corporate average fuel economy.)

The fuel-efficiency regulations will further contribute to decreasing US gasoline demand, while large investments required to hydrotreat No. 2 fuel oil at already unprofitable refineries will likely be uneconomical, causing some shutdowns. These capacity reductions will likely be a mixture of the closure of some weaker refineries and some capacity reductions in operating plants where operating older, less efficient trains is no longer economic.

By 2015, IHS forecasts margins to recover to their projected long-term equilibrium levels, based on the assumption that the global economic situation does not worsen severely (Fig. 4).

While the outlook is generally positive for both cracking and coking refineries over the next decade, widening differentials between light and heavy crude oils, along with low natural gas prices, will once again favor coking refineries, although cracking refineries in certain locations, such as the Midwest, will continue to benefit from access to less expensive domestic light, sweet crude oil.

What about demand?

Lower crude oil and operating costs help on the cost side for refiners. But, if demand for the products they produce is declining, will lower costs be enough to support the industry?

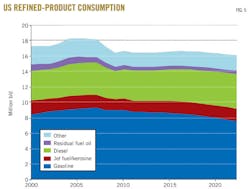

Demand for refined products in the US peaked in 2005 and suffered dramatic decline in 2008 with onset of the recession. Demand has since rebounded from its lows in 2009 but is unlikely to return to prerecession levels (Fig. 5).

Due to changes in regulations governing new-vehicle fuel efficiency and biofuels blending and in the age and driving habits of drivers, gasoline demand in the US will decline over the long term. Modest gasoline demand growth is likely over the next few years as the economy recovers, with long-term demand trends then beginning to dominate.

Increases in demand for diesel and jet fuel, which depend more on economic activity, will partially offset the decline in gasoline demand.

These factors will lead to flat to slightly lower refined product demand in the US over the next 10 years, which would seem to bode ill for the refining industry. Fortunately for refiners, however, demand is rising in emerging markets, specifically Latin America, and the US is well situated to supply this rising demand from both a location and cost standpoint.

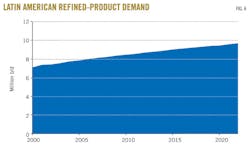

As economies have steadied and started growing, some rapidly, in Latin America over the past decade, demand for refined products has also risen rapidly, to more than 8.5 million b/d in 2011 from about 7 million b/d in 2000. This trend will continue, with demand growing to nearly 10 million b/d within the next decade (Fig. 6).

The increase in demand has come with little change in refining capacity in Latin America, meaning significant growth in imported products has been required. Adding to already increasing demand requirements is the gradual implementation of stricter regulations on fuel quality.

Many Latin American countries have begun implementing regulations requiring diesel fuel to contain less than 50-ppm sulfur, especially in heavily populated and polluted areas. Most Latin American refineries are unable to meet the new specification and therefore must import high-quality diesel in order to meet demand in these locations, while exporting low-quality diesel that cannot be sold locally.

These fuels-quality programs will continue to progress, along with similar ones for gasoline, as the benefits in improved air quality become more evident, particularly in densely populated cities, and pressure from such agencies as the World Bank continues. It is quite likely that by 2020, relatively few markets for traditional high-sulfur fuels will exist. Those markets that remain will likely be small and in potentially unstable areas such as West Africa and certain Middle Eastern countries.

Increasing demand and improving fuel quality in Latin America have been a major contributor to the US becoming a net exporter of refined products for the first time in 2009, while 2011 marked the first year the US was a net exporter of light products—gasoline, jet fuel, and diesel.

Many refinery projects have been announced in Latin America over the past several years with the aim of supplying domestic markets and curbing imports. These projects have progressed with mixed success.

Many have been delayed several times, and those that have advanced have experienced schedule delays and budget overruns.

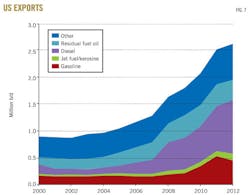

As a direct result of rising demand and lagging refining capacity in Latin America, along with increasing diesel exports to Europe, US product exports have expanded rapidly (Fig. 7).

There are several hydrotreater projects planned or currently under way to increase low-sulfur fuels production in existing Latin American refineries. These projects are necessary to keep the existing refineries viable in the face of the new regulations and will move forward. Several projects to add crude oil refining capacity at existing refineries or build new, grassroots refineries have also been announced. Little or no additional capacity, however, is likely start up before 2015 and only two major Brazilian projects (RNEST and Comperj I) and a few minor expansions, adding about 550,000 b/d of refining capacity, are to be complete before 2018-20.

In this period, plans to develop more than 1 million b/d of additional refining capacity have been announced, but the projects are still in the early stages and, given the struggles to complete current projects, it's fair to wonder whether some of these projects will be completed on schedule.

All of these factors will help keep exports from US refineries strong over the next decade.

The author

Sean DeGon is a director with IHS Downstream Energy Consulting, based in Houston. He joined IHS as part of the 2011 acquisition of Purvin & Gertz Inc. DeGon joined Purvin & Gertz in 2006 from his position as a senior process engineer at Shaw—Stone & Webster. With both IHS and Purvin & Gertz, he has conducted market analysis and performed due diligence for both refining and midstream. He also has experience as an independent engineer for project financing and in cost-estimating assignments. DeGon holds a BS (2000) in chemical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin.