IEA forecasts possible oil undersupply, price spike after 2020

Global oil supply could struggle to keep pace with demand after 2020, risking a sharp increase in prices, unless new projects are approved soon, according to the latest 5-year oil market forecast from the International Energy Agency.

The global picture appears comfortable for the next 3 years but supply growth slows considerably after that, according to Market Report Series: Oil 2017, the IEA's market analysis and forecast report previously known as the Medium-TermOil Market Report.

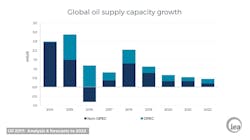

The demand and supply trends point to a tight global oil market, with spare production capacity in 2022 falling to a 14-year low.

“We have examined worldwide projects and assessed the likelihood of their completion. Our analysis suggests that, unless additional projects are given the green light soon, towards the end of our forecast horizon we will be in a 104 million-b/d [demand] market and the call on [the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries] crude and stock change rises from 32.2 million b/d in 2016 to 35.8 million b/d in 2022. With the group forecast to add 1.95 million b/d to production capacity in this period, this implies that available spare production capacity will fall below 2 million b/d,” IEA said in the report.

Demand

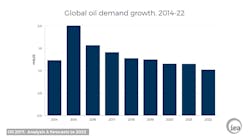

IEA’s outlook for demand in the report is little changed from the one it published a year ago: Global oil demand is expected to grow on average by 1.2 million b/d each year to 2022.

Oil demand will pass the symbolic 100 million b/d threshold in 2019 and reach about 104 million b/d by 2022. Developing countries account for all of the growth and Asia dominates, with about seven out of every 10 extra barrels consumed globally.

India's oil demand growth will outpace China by then. Indian per capita oil consumption is just 1.2 bbl/year today, and the number is expected to reach 1.5 bbl/year by 2022. This compares to China’s 3 bbl/year today, a figure expected to be 2.5 bbl/year by 2022.

“Although a direct comparison between India and China does not take into account societal and economic differences, the overall point is valid—there is clearly still plenty of growth to come from India. Indeed, that is also probably true for transportation fuels in many other developing economies, as more families move up the income scale and buy their first car,” IEA said.

In the forecast period, IEA expects that those “first cars” will almost certainly be gasoline-fueled. While the much-discussed growth in the electric vehicles fleet is a very important longer term issue for oil demand, by 2022 IEA estimates that only limited volumes of global transport fuel demand will be lost to EVs from conventional fuels.

This Oil 2017 market report also looks at the implications of tighter vehicle efficiency standards now being applied to trucks for transport fuel demand. Even though big savings will be achieved over time, within the 5-year outlook it is a question of merely slowing the rate of growth, rather than seeing a major change to the pattern of demand.

About the change in marine fuel specifications due to take place in 2020, IEA estimates that 200,000 b/d of fuel consumption will be lost to the specification change and to LNG.

In general, for all these reasons, the much-discussed peak for oil demand remains some years into the future, IEA concludes.

Supply

“With oil demand growth expected to be steady, there are many issues on the supply side that shape our forecast,” IEA said.

Global oil and gas upstream investment fell 25% in 2015 and another 26% in 2016, affecting the major oil companies and smaller independents alike. While investments in the US shale play are picking up strongly, early indications of global spending for 2017 are not encouraging.

“While the ultimate success or failure of the production agreement cannot be judged for some time, it is evident that the output cuts, totaling 1.8 million b/d if fully implemented, are taking place just as production from the non-OPEC sector as a whole, led by the US, is actually recovering—after falling in 2016 for the first time since 2008—and when stocks of crude oil and products are at record highs. This scenario of ample supply, even as output cuts are implemented, explains the very flat crude-oil price futures curve on which our 5-year forecast is based,” IEA said.

“Another period of falling prices could have further pushed back critical investment decisions, and threatened the production recovery needed in the second half of our forecast. As it stands, when investment does recover, it will serve an industry that is far leaner and fitter than it ever was and that will be able to deliver more with less.”

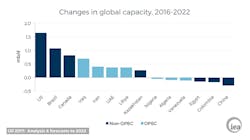

In the next few years, oil supply is growing in the US, Canada, Brazil, and elsewhere but this growth could stall by 2020 if the record two-year investment slump of 2015 and 2016 is not reversed.

"We are witnessing the start of a second wave of US supply growth, and its size will depend on where prices go," said Fatih Birol, IEA's executive director. "But this is no time for complacency. We don't see a peak in oil demand any time soon. And unless investments globally rebound sharply, a new period of price volatility looms on the horizon."

The largest contribution to new supplies will come from the US. The IEA expects US light, tight oil production to make a strong comeback and grow 1.4 million b/d by 2022 if prices remain around $60/bbl. Expectations for US LTO are higher than last year's forecast thanks to impressive productivity gains.

The US responds more rapidly to price signals than other producers. If prices climb to $80/bbl, US LTO production could grow by 3 million b/d in 5 years. Alternatively, if prices are at $50/bbl, it could decline from the early 2020s.

Within OPEC, the bulk of new supplies will come from major low-cost Middle Eastern producers, namely Iraq, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates. Others like Nigeria, Algeria, and Venezuela will decline. For its part, production from Russia is forecast to remain stable over the next 5 years.

Trade, storage

The report also highlights changes in international oil-trade flows and investments in storage infrastructure.

Asia will need to look beyond the Middle East to meet its growing import requirements. According to IEA’s forecasts, net export flows from OPEC countries—incorporating growth from the main Middle East producers but declines from elsewhere—will increase 500,000 b/d. This is significantly less than the forecast incremental growth in export potential from Brazil and Canada of 1.6 million b/d.

The Middle East producers, traditionally amongst the leading suppliers to growing Asian markets, cannot alone meet the growth in Asia’s crude import requirement which will rise from 21 million b/d in 2016 to 25 million b/d in 2022 due to growth in demand and the decline in regional production.

Evolving trade flows highlight the need for additional storage capacity. Over the past 2 years, a global supply overhang created trading and storage opportunities, particularly in non-Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries, where rising demand and import requirements have led to a build-up of strategic and commercial reserves. The report, for the first time, provides an in-depth review of global storage developments to highlight where investments are being made.